White Devil

Paul Maheke solo show.

For his second solo exhibition at Galerie Sultana, Paul Maheke delivers an arresting title upon which we can only stop. It is then necessary to choose whether or not to open the Pandora’s box. And give up on certainties in order to perhaps be swallowed up by the abyss; Where, perhaps, in the midst of the fabric of the Western collective unconscious, what is what is left for us to be seen might not be pleasing; Where beliefs coexist alongside archetypes, and where the deepest fears thwart the linearity of history with repeated appearances. But this is just speculation, Paul having handed over this title to me as a cheeky nod with multiple and timely meanings. White Devil…an idiom alluding to whatever goes against centuries of Christian iconography. To assert that the association between the colour black and anything evil is a constant, is stating the obvious, ranging from the representations of the devil in medieval Europe to the witches practicing black magic. History is brimmed with examples of shortcuts arisen from such association, like during the early days of colonial America, when British immigrants multiplied accusations of witchcraft. At the end of the 17th century in Salem, the devil seemed to be everywhere; and although it took alternately the form of a Jew or a dog, the texts mainly point out to black and indigenous bodies as incarnations of the Devil, thus the quasi systematic association of the two. The persecutions, in turn, are perpetuated for the sake of defending the colony of the people of God who have settled on satanic grounds*.

In recent years, Paul Maheke’s practice manifested through the emergence of colourful territories composed with apparitions and presences. As if to escape the regime of the visible and its categorizations, they manifest themselves in multiple and elusive ways, from within the fluidity of transitional spaces, in-between images, texts and objects. They drown in light and evade through the sonic cracks of a reality – imagined by the artist as a an emancipatory third space where representation or words do not hold on to their fixed meaning. When a body appears, it is often Maheke’s, or that of his collaborators turned-hosts of a certain multiplicity, of ruptures in time, and spaces shaping improvised gestures draw.

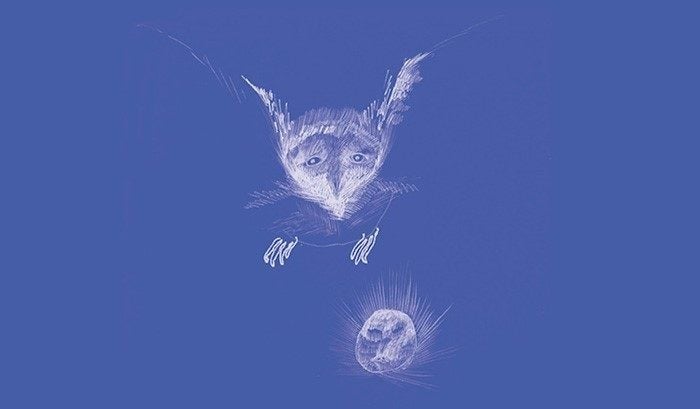

However here, no body will manifest itself in the flesh to the visitors of White Devil. Human figures are here encasted inside the material, in broad daylight and full transparency, as an imprint of torment, or the remainder dread which cause shall not be named. Does this plunge into the field of representation is omnious? Like the sight of an owl in broad daylight? The announcer of death, companion of the devil and deceit as well as a symbol for wisdom and perceptiveness, it is indeed an owl who welcomes us at the gallery with its round eyes, capable of seeing in the dead of the night. The bird emerges from an azure blue background bathing the gallery in a blue hue and reminds us, perhaps, of how a small amount of this pigment can give the illusion of a whiter surface. These confusions and reversals in values and chroma thread through Diable Blanc. Two words which, it must be said, are also a historical metaphor to address the systemic oppression built on whiteness in America…from colonization, to Jim Crow, to today’s police brutality. White Devil, this white devil, is therefore a character who does not age; it travels through the history of its multiple appeareances, reaffirming a domination that did not just remain the prerogative of the Old South’s blues.

It is precisely on a journey towards the end of this century that Paul Maheke takes us. Because when blues developed in African-American communities of Southern United States, digging into Faustian romantic myths, the songs of the plantation, and vernacular traditions of Northern America and West Africa, Europe is working its way through the end-of-the-century racism, which is based on a transposition of Darwinism into Human Sciences. Back then, we categorize, and ambitiously attempt to descibe and represent human society using the precision of zoology. We are interested in the social as much as we are in the medical realm, reading the organic into the psyche. This end of the century is a passage, as is the work of many artists, who haunt the bodies Paul Maheke is presenting us with. We can freely recall those artists who, at the end of the 19th century, continued to seek the truth in the observation of Barbizon’s forests, just like their mentors. We can think of the crisis of naturalism, the rise of symbolism… artists like Carlos Schwabe, Mallarmé’s illustrator Michel Fingesten and his prophetic engravings, and of course, Redon.

Redon, who mastered the art of the depicting the struggle between light and shadow, who in each of his works seemed capable of carving out new territories within the unconscious. An artist whose Wagnerian imagination was feeding on the idea of a stateless-elsewhere, fantasized between the Louisiana of his Creole mother, and his wife’s island La Reunion Island. A quest that, in an context wherein which naturalist criticism feeds into various forma of nationalisms, and eventually turned to colour and «the supernatural quality of nature»

It is therefore at the root of this appetite for conquerring and understanding of the world that Paul Maheke takes us to the confines of chromatic visions which at times lean towards the abject; between the appeal to transparency, order, shadow and light. In the midst of these vibrations where opposites enter into a dialogue and the invisible is not necessarily intangible, Paul Maheke invites us to explore the representational possibilities of another form of corporeality. The one, perhaps, described by Ralph Elisson in his novel «Invisible Man», (1952) and whom Fred Moten pleads as a profound invisibility which would bring visibility to its core. Because what is invisible here is also profoundly physical, epidermal, acoustic, on the surface and below.

Céline Kopp

Notes :

*See «Cotton Mather, Puritan theologian, The Wonders of the Invisible World. Observations As well Historical as Theological, upon the Nature, the Number, and the Operations of the Devils». (1693).

Fred Moten, «In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition», 2003