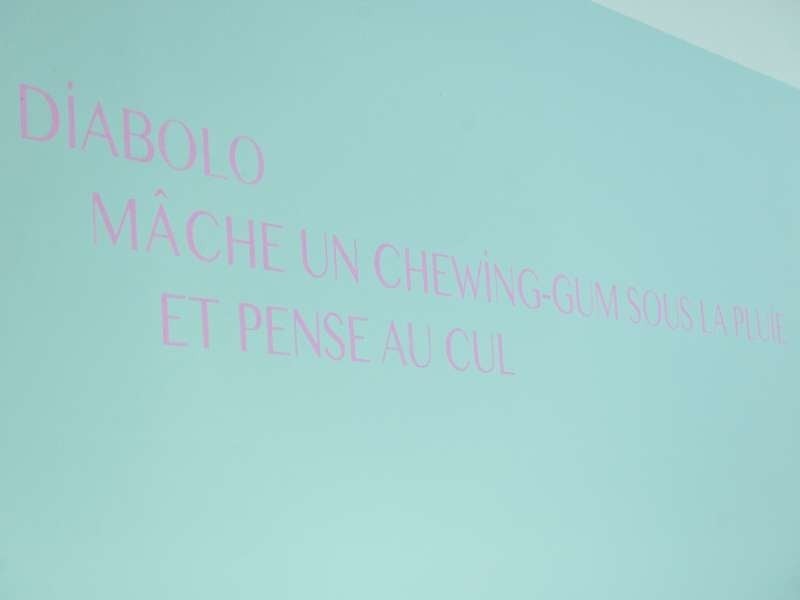

Diabolo mâche un chewing-gum sous la pluie et pense au cul

The characters that Sarah Tritz has summoned to the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard – such as the melancholic Diabolo, after whom the exhibition is named, and the delightful Sluggo, both of whom are taken directly from an American comic from the 1930s, from where the artist also borrowed the delicate sky-blue and water-green colours that decorate the walls of the space – bring in their wake a cohort of mystery guests.

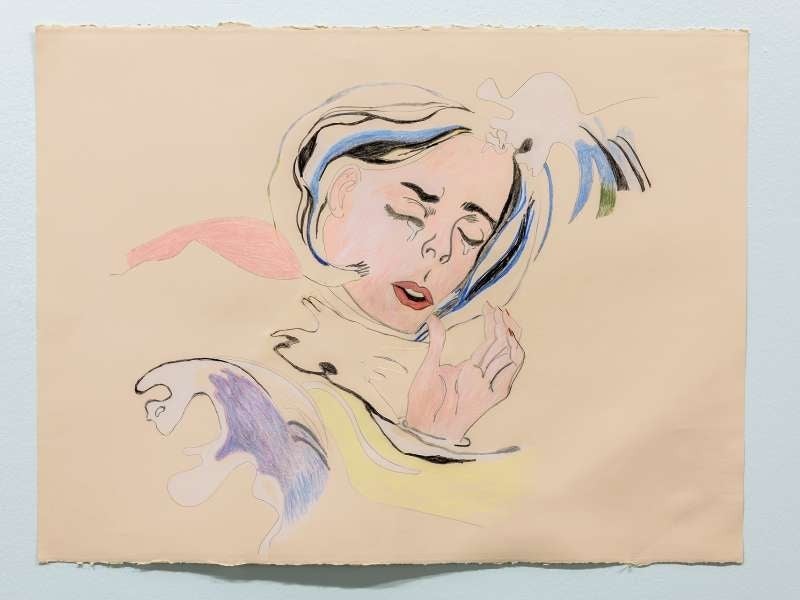

Forgotten relations and illustrious elders that Sarah Tritz has picked from the sieve of the history of art and that haunt the chequered lineage of the characters in her work: Picabia and his bride, to whom Tritz has given the task of welcoming the visitors to the exhibition, Roy Lichtenstein, who inspired her drowned woman, the German painter Willi Baumeister, from whom she borrows a fresco titled Afrika and makes a grainy replica on the back of a partition wall, and Max Ernst, whose small drawing she unfolds to cut out the sharp edges of a three-dimensional totemic Giant.

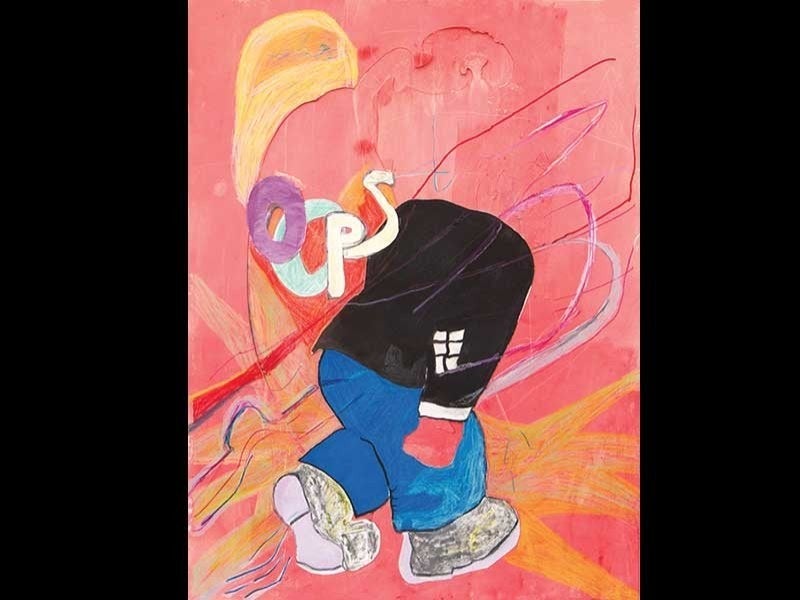

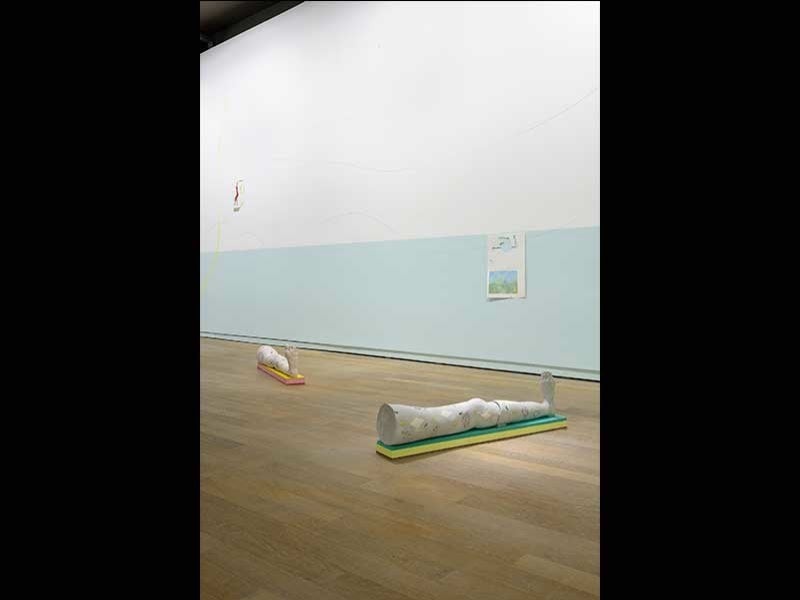

Everything in this miniature theatre is an interplay of vanishing points and perspectives. Look at Sluggo, whose head, separated from the rest of his body (which has nipped off into the next room), lords it like a trophy over the fireplace at the centre of the exhibition. With a little sidelong smile, he winks at the weeping woman on the wall opposite. Next to him, a short-legged smiley mocks the clumsy representation that Tritz – taking her inspiration from a beginners’ manga manual – attempted on a tile of fresh plaster. And as for the legs placed on the bubblegum-coloured dance mats, you can be sure they are spying on us all.

Here we all squabble and shove one another to get a good place in front of the setting sun before which only Charlotte, a languid sculpture lying on the ground at the start of the exhibition, with her sex made from cob and feet up, seems to be fully relaxed. It has to be said that in this orgy of pastels, this unnatural wedding feast, there is something rather gently weird about the characters. The reason is probably the above-mentioned selections, and the way that Sarah Tritz creates her works by calling on figures from different artistic milieus, one might almost say different social classes – surrealism, tribal arts, the decorative arts, and even cut-rate comics. “It is in the discrepancies of style that I involve the onlooker’s perception; it is by means of the acrobatics that this difference compels that I imagine the onlooker becomes active”, she sums up. And indeed, we wander around amused, glancing here and there, from one character to another. In the same way, Tritz employs understatement and dismembers some of her sculptures, showing here just a pair of legs, there a disjointed arm; with a view to effectiveness and simplicity, we have to accept the fact of acquainting ourselves with these details on a one-to-one basis so we can then choose to take in the whole of the exhibition.

Created exclusively in 2015, with the exception of the large collage in primary colours in the first room, Sarah Tritz’s works – dressed up to the nines or a little rash when they once again take up techniques of the craftsmen to whom the artist delegates some of her work in order to increase the effects of imbalance – succeed in being perfectly independent yet also extremely sociable. Despite their differences.

Claire Moulène, november 2015