City Rumours

Liza Maignan is the laureate of the second edition of the TextWork Writing Grant

— I’m going to the ‘Plateau’, is it still far?

— You’re already on the ‘Plateau’. It’s there. It’s everywhere.

So how does one find oneself on the Plateau de Millevaches? I didn’t really know the history of the ‘plateau’, nor of the Limousin region, and even less so of the Corrèze department. For me, as for many children who didn’t grow up in the Paris region, this rural and central area of France was in the middle of nowhere—or, as we put it today, in the ‘diagonale du vide’, the ‘empty diagonal’ crossing the regions with the country's lowest population density. As I stumbled into my thirties in a post-global pandemic period, I began hearing people speak of their desire to move to the country, to ‘go green’. But the risk of living in rural areas is that it’s freezing in the winter and you can quickly feel lonely. And that has a price. So, moving to somewhere greener has become a classic debate around a five-euro pint. And you, would you be ready to leave Paris?

I discovered Corrèze, not through the art world (my professional field), but through an old friendship. I was regularly on holiday in the region and soon discovered several independent and self-managed places such as Treignac Projet and Cocotte in Treignac, the Amicale mille feux in Lacelle, Fossile Futur in Meymac. I consequently came to know certain people who founded, experimented with and inhabited these spaces and the territory they call home. Chloé Munich, Vincent Lalanne, Olga Boudin, Tatiana Pozzo di Borgo, Laura El-Beze, Julien Salban-Crema, Sam Basu, Maxime Bichon, Matthieu Palud and Louise Sartor, Charlotte Houette, Avril Tison, Simon Dubedat, Sarah Melen, Pacôme Ricciardi, Baptiste Perotin generously shared their stories with me—over a meal, during a walk, with a glass of water in the sun or a herbal tea by the fire.1 I have never addressed any of these people using the formal term vous, and for some of them, I had never heard their last name before asking to incorporate them as subjects into my research, tumbling into a more formal context beyond our spontaneous encounters. So I will address them informally, as I have from the beginning, and I will use their first names to mention them, as I do on a daily basis. Because, outside the social space of contemporary art, our last names are not business cards that can be Googled. And, for my part, I am neither a journalist, nor a sociologist, nor a historian, nor an economist, nor an artist. I don’t really know what I am, but I know what I’m doing.

Leaving Paris

The daughter of my friends is so proud to say that she was born in Paris. On the day she was born, I looked after their dog. For several days, I proudly walked the streets of Le Marais with my dishevelled dog pulling on her leash. Paris is filthy—having a dog in Paris is filthy. Disillusionment set in as I noticed the white cushion in her basket turning grey. It didn’t surprise me when, a few years later, my friends announced their decision to leave Paris. Before departing, they listed all the French regions in an Excel spreadsheet, and the criteria to consider when choosing the place most adapted to their needs. It was an important tool that helped them define the outlines of the political everyday in which they wanted to settle.

A few years later, Olga and Julien in turn explained to me how they and other members of the Amicale mille feux got to the Plateau de Millevaches. In 2015, when they were students at the École des beaux-arts de Paris, they had heard of the links that the students in Jean-François Chevrier’s seminar had developed and maintained with the Plateau de Millevaches, in particular with the Peuple et Culture Corrèze association, based in Tulle.2 In 2009, the RADO group was formed around eight artists: Fanny Béguery, Madeleine Bernardin, Florian Fouché, Adrien Malcor, Anaïs Masson, Maxence Rifflet, Claire Tenu, and Antoine Yoseph.3 Between 2011 and 2014, RADO developed a long-term project titled Ce qui ne se voit pas, followed by a travelling exhibition of the same name in 2014 at the Saint-Pierre church in Tulle and at the Centre international d’art et du paysage (CIAPV) in Vassivière. They worked with residents to make invisible activities visible, through photographic documentation, installations, or even the creation of editorial documents such as the Rapport sur l’état de nos forêts et leurs devenirs possibles.4 For this exhibition, they performed their gestures, mobilised their gazes, put their tools at the service of locals who carry out struggles, perpetuate their craftsmanship, recount forgotten local stories, and engage in practices within their social environment, in order to document the ‘country of Tulle’ and the uses of this territory by the locals.

The discovery of these artistic activities and this territory allowed Olga and Julien to consider the possibility of settling on the Plateau de Millevaches, and more precisely in the village of Lacelle, in order to continue working, to make art (or not), to think about how to live differently. Because what seems to connect each person from the Amicale mille feux, or from Fossile Futur (which was established in a nearby town a few years later) with one another, is a desire to leave something behind that does not suit them, to fulfil a need for emancipation and autonomy. That something would be an excess: an overflow of problems, unstable economic conditions, institutional integrations required for a practice to exist. A desire to cut themselves off from everything else so that they can rebuild their spaces, reconfigure their rhythms, redefine their ways of living and working, both of which are inherent to their political postures. Militant, political, and philosophical presences and activities, which have multiplied on the Plateau de Millevaches, particularly in the village of Tarnac, have also confirmed this desire for territorial anchoring, historically infused with and carried by other national or international struggles, such as in Larzac in the 1970s or the Notre-Dame-des-Landes ZAD5 set up in the 2010s by objectors to the Grand Ouest airport project.

And along the way, Millevaches turns into milfoil

It’s summertime and Greece is burning. I’m in my mother’s converted truck, we’re driving through the Périgord-Limousin Regional Nature Reserve. Through the window, I’m watching the trees go by—the powerful green of the leaves soothes my eco-anxiety attacks. While we’re on our way, I receive a text from my friend Franck: he will be at Treignac Projet tonight for an opening. We decide to deviate slightly from our route and join him there, in the village of Treignac. I wander with my mother by my side in the former spinning factory—for almost seventeen years this place has been occupied by Sam and Liz, as well as temporary communities, or loners who take up residence there, mainly during the summer. I quickly identify Sam, with his hair tied in a bun. I don’t know Liz’s face. I didn’t speak to them that evening. Sam and Liz are the captains of this ship of bricks and concrete, sexy because it’s post-industrial to the core. I don’t really understand the operation mode of this labyrinthine place, despite being accustomed to large spaces with grey flooring and white walls. I understand that there are dedicated rooms: the exhibition rooms, the kitchen, the club, the recording room. I don’t know whether there is a truly ‘private’ area, for Sam and Liz’s daily life, or if each room is public. To some extent, I recognise something of the function of these large buildings, in which it is cold in both summer and winter, and where work is continuously underway so that this imposing yet equally fragile edifice does not collapse.

During the evening, my mother introduces me to Matthieu. Matthieu introduces me to Louise. The next day, we meet them again. This time, we walk further up into the village through one of the main streets. At Louise and Matthieu’s place on the ground floor, we discover their space Cocotte, which I imagine to be a former shop, with the front door between two large windows pierced in the walls making up the street corner. Cocotte is a bright room—its walls are also white, which gives pride of place to the other rooms. Louise and Matthieu’s living space is upstairs. This house belongs to Sam and Liz; they make it available free of charge. It is an appendage, a stand-alone annexe of Treignac Projet, the old factory further down the village.

What can we do when we’re among friends?

As I’m writing these words, Cocotte has left Treignac. Cocotte no longer has an address and doesn’t yet know in which form it will continue to exist. Cocotte stayed in Treignac for almost three years. These sister buildings are like large cooperative vacation homes. They do not wish to conform to a time-controlled environment as is expected of a (cultural) public service. The provision of their time is offered without expectation, without return, escaping the constraints of a predefined calendar, free from any financial authority, devoid of the search for individual recognition. They welcome friends, friends of friends, met here and there—to sleep, to work.

At Cocotte, invitations are presented to me as subjective, without a clear logic or strategy—except for the desire to surface names6 that aren’t already on everyone’s lips in the institutional world, like yet-to-be-drawn cards in a game of Happy Families. For some, the sole purpose of showing their work at Cocotte is the pleasure of seeing it exist in a dedicated context and temporality. With each invitation, the situation changes. Even if the kitchen and bathroom are still shared. When there is no money, relationships are different. When there is no money, things are done differently. ‘The important thing is to know what you have to offer’, Louise tells me. The exchange is based on the encounter, not on a financial aspect. These places can escape the diktat of remuneration, because the added value, the real resource, is the people, and there is no profit to be made from that.

For Maxime, a friend of Treignac Projet, this place is already an artwork in itself, because it meets all the conditions required to produce reciprocal conviviality: ‘If you come to Treignac Projet, you give to Treignac Projet.’ It is a two-way generosity, an abstract space which presumes friendships7 before they exist, in an eternal renewal, since at Treignac Projet there is no project, no predetermined operational terms, no goal to achieve. We pass through Treignac Projet like in a broken memory palace: our goal is forgotten at every door, and we go from threshold to threshold.

I wonder, then, whether it is not ultimately an unconscious form of capitalisation on friendship, which implies a form of mutual interest, not to be considered negatively: if I am friends with you, it is because I have an interest in you for various reasons (intellectual, emotional, relational). I can already hear some of you complaining about a form of ‘self-containment’. Yes, it is self-containment, though it should be considered as an integral part of the making of broader relationships, beyond a normative family system, only based on friendship or purely professional; a necessary space for a group to express a desire to exist outside institutions, money, or any form of authority, and allow for the creation of other types of relationships, with their own rhythms, their own systems. It is also the reason why time stretches out in Treignac, Lacelle, or Meymac; because the temporality in these territories allows for various possibilities of encounters—an adjustment of relational time allowing us to live under the fantasised regime of idiorrhythmy,8 taking into consideration both solitary rhythms and community rhythms. Existing outside of a ‘dominated’ time or space9 induced by the State organisation and the capitalist rhythms of our cities, these counterspaces open up the possibility of a reorganisation of social life, in particular through artistic creation.

But then, what are the risks of leaving the art world? There are no risks.

I’m sitting in the sun in the Amicale mille feux garden with Sam, who has had too much coffee. He came to tell me the story of Treignac Projet, with his English accent that I don’t always understand. I often ask him to repeat, he gropes for words, we speak Frenglish and laugh. The sun is beating down on the white plastic table, on which there are still puddles from yesterday’s rain. Sam considers that the condition for finding this paradise is to accept loss, the impossibility of being elsewhere. Sam is aware that there are several lives within a life. According to him, not being something is a form in itself. For most of us, it is impossible to be a full-time artist-author without a family that helps you or a day job (which necessarily makes you something other than a full-time artist-author). Even if your social class does not change your ability to be an artist, it affects the possibilities of you being one entirely. So you always have to ask yourself, what do you lose/what do you gain? No matter. If you gain something, you will always lose something else. So let’s accept losing one life for another. Withdrawal isn’t a subcategory of choice, we do not topple into the regime of less (−). The value of our life is not in deficit, but it is balanced out with an excess, allowing us to find equilibrium between burn-out and bore-out.

Sam says it’s like staying in a grieving phase, it pushes you towards the future. It allows you to still be connected to the past. Feeling an end, and finding possibilities to continue anyway. It allows you to remain in a state of tension, to remember what you have left behind and to remain in control of the future—and preserve what has happened. Sam knows that when the building is finished, the project will be over. But he does not want the project to come to an end; he prefers to maintain a relationship with what is not finished, as with the industrial history of the building. The movement of withdrawal in geographical and social decentralisation does not bring about a change of forms, but allows for a scattering towards a restructuring of the modes of existence of art, the creation of diagonals, the redistribution of focus and resources. We agree to say that rural life does not lead to a new form of art, but it allows for a behavioural change, towards objects, processes, the way of explaining things and welcoming others. The question of art remains, but the relationship to art changes, as well as the possibilities for an object to exist. While relational aesthetics—overplayed in art institutions—has failed to find where it belongs, it remains where it first emerged: everyday life. We should then ask ourselves: who has the authority to say and make art?

Everyday life is not visible

Sam tells me that, here, they escape the belief that art will save the world, and try to focus on relationships, because art allows the intersection of disciplines and therefore of people. But encounters that take place around an object A are impossible to aesthecise—these things are not quantitative. It is this relationship that we are all trying to connect with, to understand. It is this relationship that we call public. Here, there are some curious locals, certainly, though often knowledgeable because coming from a close cultural background, and there are friends from Paris or elsewhere, or the digital visitor who hits the like button relentlessly. I have the feeling that these places are spaces of generosity which do not seek to respond to expected ways of existing, and onto which certain people will project a form of purity, trying to figure out at all costs whether they ‘work’ or not. That’s not the question. These initiatives exist. And the people taking care of those spaces invite, welcome, invent, exhibit, program, accompany, prepare good meals for themselves and the people of the village, and document (some of) it. Also, the benefit of living in the country, of being on the fringes, is that you cannot be disappointed with a lack of audience, since no audience is ever really expected. Each additional spectator is a bonus. Without expectations, there is no disappointment. The moment exists as we exist through it. Everyday life is not seen, it is lived—like the reciprocity of an emotion, it cannot be archived.

Living in a village of 130 inhabitants is a question of harmony. People need to tame one another. There are always stories, cronyism, emerging political and generational gaps. Newcomers always arouse curiosity and gossip. Another question often comes up: how can we make these places exist and make them welcoming, without feeling like parasites or troublemakers? Julien explains to me that they realised that when they’d put up posters in Lacelle to communicate about events at the Amicale mille feux, the villagers did not feel invited. Indeed, when you are foreign to a space, or a group (however open it may be), it is very easy not to feel justified in attending an artistic event, a musical event, an activist workshop—you feel far from this field and these concerns. You are always afraid of not understanding anything, of feeling stupid, of not being included in discussions. A balance must be found in the communication and transmission of the intention. The Lacelle residents seemed to think that the presence of posters in the village was a way for the Amicale to say: ‘It exists.’ Now, the invitations are put one by one into the residents’ mailboxes, so that they understand the intention: You are welcome. In this bundle of collective involvement and cohabitation, there is always the negative aspect of promiscuity and confrontation with external personalities who hardly appreciate other people’s lifestyles. So they have to deal with all these parameters.

Listening through the walls of yesterday

The residents of the house called Fossile Futur tell me with emotion that, on one afternoon, an elderly couple came in through the always-open door and shared with them the story of how they first met in that very house, the former bank of the village. He was an employee there and she was a waitress in the restaurant across the street. Their story wrote itself from the windows of both buildings facing each other, by the side of the road that separated them. Here’s another story of walls: Sam tells me that during the first public openings, people who had worked in the factory came to rediscover the building and recount their worker’s stories. Buildings have stories. In producing new gestures in this building, an old spinning factory, the gestures of the workers that became obsolete when it was closed are withdrawn. New lives are written for these buildings, and these stories will one day be the past stories of these places, constituting the breeding ground for other experiences, and their memories.

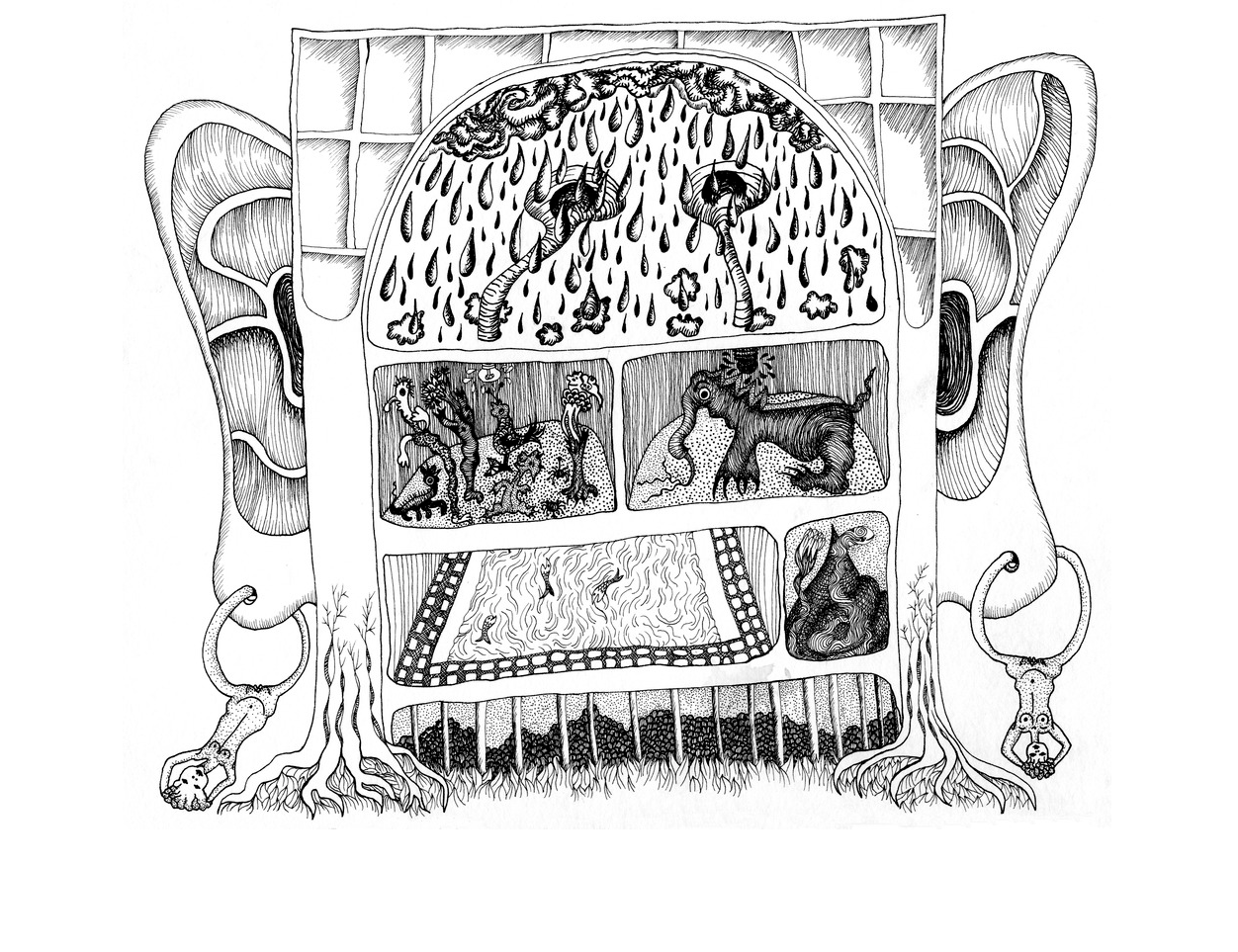

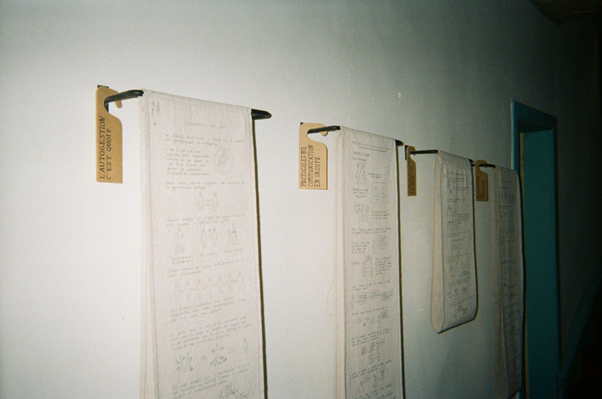

The Fossile Futur house (initially made available rent-free in exchange for its upkeep) has been home to the eponymous, multifaceted collective for almost two years. Founded at the institut supérieur des arts et du design de Toulouse (isdaT), the collective counts around ten members, two of whom live here all year round, while the house is a point of contact for the others, a temporary workspace, a long-term project, a place of withdrawal, of rest. At the entrance, a small leaflet and screen-printed banners, designed by Simon Dubedat and Léa Chaumel, set out some recommendations considering the functioning of the house and cohabitation with its daily and temporary residents.

Simon is a designer. For several years, he has been developing tools to facilitate group communication, speech systems co-organised around mutual respect. He explains to me that he had started to think about a whole series of open-source objects, content, and systems that he discovered while exploring various collective places. Raising a finger, raising another or a third one to define your place in the speaking order, voting in a non-binary way to provide more diffuse and nuanced opinions, etc. Simon is currently developing the prototype of a board game that brings together all of these systems, aiming to allow collectives, or any other type of interested institutions, to understand the relationships of domination which may arise during meetings or debates. These methods of collective speech were implemented in the daily life of the house, where they continue to be tested, so that each resident may find their own rhythm, balance, and ways to participate within the group. In short, they are open systems thanks to which people who cannot find their place in collaborative workspaces may do so more easily. I exist by talking about you. I exist with and through you.

‘Faire fleur’,10 emerging from the soil to cause tripping

It’s summertime once again and, this year, it’s the Atlantic coast that’s ablaze. Olga and Tatiana welcome me to their home, the former post office in Lacelle. Inside, there are rainbows reflected on the walls and holes in the floor that you need to watch out for. This house is just a few metres from a large building that stands before us when we get off the train at the small Lacelle station. This large building is divided into two parts: the first wing can be accessed through a yellow metal double door that stands out from a distance; the front side of the second wing features a more discreet glazed wooden door. In the centre, a French window blocked by a wooden bench, and a few posters—one of them reads ‘On strike until retirement’ with a mischievous little pink dog holding a ‘Borne Out’ poster in its mouth.11 My memory of the other posters is too hazy. When you look up, you can see four drawn letters: F-E-U-X, and just above them, the name of the house engraved on wood: ‘Amicale mille feux’. In the left wing of the building, there are two apartments where Julien and Laura live—I had not seen them since the end of our studies.

Julien and Olga, who share an affiliation with Paris Commune thinking, look back on the various stages of their friendship before settling in Lacelle: one year of protest against the El Khomri law back in 2016, a three-day takeover of their school (a short one, certainly, but something which had not taken place since 1968, according to them), establishing a squat where they lived for a while in a Parisian suburb, and the development of a daily editorial practice, in the form of a DIY publication compiling their respective readings and writings on political and artistic topics. This weekly publication was their way of drawing a parallel between art and politics, and creating a common discourse for the activist public that they were involved with at the time, in order to bind often opposite concerns together.

Back then, Julien was a street bookseller. He had analysed the book distribution market and he dealt directly with publishers to acquire and resell books at cost price. Julien was a hawker with an empty purse. He’d lay his merchandise in transit and waiting areas, in train stations, on bus stop benches in Paris, Marseille, Limoges, and many other cities. He’d quietly sell books and magazines which spread the political ideas that he defended. He developed contexts for the circulation of thoughts, such as the subjective libraries which he created according to the classifications of his own book collections. Now Julien is an artist/beekeeper/sex worker. His practices are developed in reflection of one another and have become a method of survival so as not to be affiliated with a single task (like bees, which have seven). They allow for a diversity of thought, production, and economy. Olga is a painter/founder and editor of the Hourra publishing house/municipal councillor at the Lacelle town hall. She paints flowers, pattypan squash, and tools. She paints a timeless everyday banality, anchored in a given temporality—her own. Her editorial practice allows her to express her political stance and to fully and consciously embrace her desire to paint as a purely pictorial gesture, devoid of any militant intention, although it inherently carries political meaning.

Better bread in the lap than feather in the cap

Back in Paris, strikes come one after another. We’re afraid for our pensions. Like a dream, I remember the story of Julien and Olga and their crafting experience of a twenty-metre-long dragon made of fabric, a human float animated by a smoke system, inside which Amicale mille feux members would often parade to oppose the construction of a new factory on Corrèze soil. After this victorious battle, the dragon (a metaphor for the factory) integrated a carnival-like choreography to fight the famous newt of Notre-Dame-des-Landes for the ZAD’s annual festival. I also recall the Bread and Puppet Theater,12 a US-based radical theatre company which put together street shows of papier-mâché puppets in the 1980s representing historical figures or political oppressors from that time, and played sketches as part of demonstrations, parades, or reenactments. Among other places, the Bread and Puppet Theater sets up in working-class neighbourhoods, and runs participatory puppet-creation workshops, which generates meeting spaces and conviviality between residents, as well as new forms for shared struggles to be carried forward. To this should be added stories, as indicated by the name of the company, of making and distributing bread during performances, because according to Peter Schumann, one of the co-founders, art ‘is as essential to the human being as bread is’.

These forms of living and creating together not only produce new times and spaces for meetings, productions, words, struggles, and sanctuaries, but they also constitute the living archive of a fabric that can be rolled out anywhere. To each territory its own struggle—and if the land to be defended is already covered with weapons or concrete suffocating its inhabitants, then it becomes about joining the resistance, and a struggle for social ecology takes place. In 2022, documenta fifteen in Kassel, Germany, highlighted the shift from individual forms to speech-carrying community forms, in which archives, documentation, the setting-up of radical libraries,13 or living presence, would be new ways of making the entity ‘art’ one’s own, as a dissemination channel for these daily practices. Sometimes impoverished, sometimes overflowing with materials, words being uttered, or historical vernacular forms, these aesthetics steered us away from the aesthetic criteria known to our Eurocentric views and critiques. As apathetic spectators of these unknown territories and struggles, we found ourselves astonished and our minds dazed considering what we expected from a manifestation of ‘contemporary art’.

I recently realised that art schools—and for that purpose, they must survive—are not only institutions operating to ‘make artists’, quite the contrary. Because the stories told, here and elsewhere, find their sources within art schools, in a relationship between the users of these institutions (students, teachers, technicians, etc.). These schools are home to social beings who collectively develop ways of thinking about the world—their world—and modify the relational paradigms in other professional fields. (It is not a failure, it is our strength: we interfere everywhere.) How many times have I cried my eyes out, telling myself that the art world in which I evolve is useless, that it won’t change anything in a world ablaze, suffocating us, that our artistic existence has no immediate effect on current social, economic, and ecological issues. Art alone is useless, it has no impact. But it can be thought of as a dissemination channel for ideas, and attempts on our scale. It’s again the old story of the mourning process, to accept what we lose—direct recognition, an ideal economy, though almost non-existent for the majority of us—and to understand what we find in exchange. So, it’s OK not to be a full-time artist after leaving art school while working multiple jobs to try and live a little doing a bit of what you love. There are necessarily other forms, other postures (other than that of an obsolete and condescending dandyism) that allow one to be what is administratively known in France as an ‘artist-author’. With art—this abstract entity— we cohabit and create networks of beings that develop resources of solidarity, spaces for shared thoughts, and points of contact—a large canvas to which we are all tied, and thanks to which we cannot fall. Recently, I realised that I was no longer afraid of getting lost, that I had the feeling that, in each region of this country, I had a possible connection with one or more people still linked to art, or not, but in any case, people who could welcome me, with whom I could stay, eat, take refuge, and that reassured me a lot.

Immersed in the observation of my own daily life with its constant paradoxical demands, I do not feel justified in writing this text without your stories, and you do not feel justified in telling me about your personal lives, even though they are the driving force behind salutary energies. They situate us on the scale of ethics. Our thoughts are stories before becoming theory, so that they resonate with others, elsewhere, to weave and create solid links. However, I still wonder how to resonate with your stories, which I haven’t lived; how my words can find accuracy in their transcriptions, biased by my own personal story and the interest that I have in you, at first glance for no explicable reason. Between these lines and the roads that bind us, there is no truth, no answer, only attempts to tell a story, in order to understand how to deal with things, differently.

Translated from French by Matthieu Ortalda

These meetings took place between March and June 2023.

Peuple et Culture Corrèze is part of the Peuple et Culture network, which currently comprises fourteen associations: ‘Peuple et Culture Corrèze operates within the territory with a strong commitment to its roots, maintaining the “generalist” nature of popular education provided through both artistic and political aspects.’ https://peupleetculture.fr/presentation, accessed July 2023.

About the RADO group, https://groupe-rado.jimdofree.com, accessed July 2023.

Report on the State of Our Forests and Their Possible Futures.

Zone à défendre, zone to defend, an occupation intended to block a development project.

Jacent, Charlotte Houette, Malak Varichon El Zanaty, Marie Schachtel, Olivier Douard, Matthieu Palud, Louise Sartor, Sam_Liz (Sam Basu & Liz Murray), Mathis Collins, Kim Farkas, Léo Forest, Clio Sze To, Mona Varichon, Fabienne Audéoud, Christophe de Rohan Chabot, and Naoki Sutter Shudo.

Presumption of friendship, a term used by Sam and Maxime during our meetings in May 2023.

Roland Barthes, Comment vivre ensemble. Simulations romanesques de quelques espaces quotidiens. Notes de cours et de séminaires au Collège de France (1976–1977), Paris, Seuil/Imec, 2002.

Kristin Ross, La forme-Commune, Paris, La fabrique éditions, 2023, p. 99.

Faire fleur was the title of Olga Boudin’s 2023 solo exhibition at 30 rue du Docteur-Potain, Paris.

‘En grève jusqu’à la retraite’, risograph print poster, 29.7 x 42 cm, Paris, Editions Burn-Août, March 2023.

Françoise Kourilsky, Bread and Puppet Theater, Lausanne, La Cité, Théâtre vivant collection, 1971.

Lou Ferrand, Bibliothèques radicales - Archives et reading rooms à la 15e édition de la documenta, Kassel, Jeunes Commissaires / Institut français, 2022, accessed July 2023, https://www.jeunescommissaires.de/bibliotheques-radicales-archives-et- reading-rooms-a-la-15e-edition-de-la-documenta-kassel/