Embodied Infrastructures and Other Tendencies for Collective Action

Cassandre Langlois is the laureate of the third edition of the TextWork Writing Grant

Text by the artist, written for the performance.

Alexander G. Wehelyie, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten define “undercommons” as a place of uncertainty, of collective creation, informal exchanges and improvisation.

“The General Antagonism, an interview with Stevphen Shukaitis”, in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The undercommons – Fugitive planning and black study (Montreuil: Éditions Brook, 2022 [2013]), 132.

Sara Ahmed, Vandalisme Queer (France: éditions Burn-Août, 2024), 29.

Inspired by Paulo Freire’s work, these practices involve feminism, queer, anticolonialism, the critique of norms, and ecological forms of pedagogy.

Nora Sterneld and Luisa Ziaja, “What Comes After the Show? On Post-Representational Curating”, OnCurating, issue 14 (2012): 21–24. See https://www.on-curating.org/files/oc/dateiverwaltung/old%20Issues/ONCURATING_Issue14.pdf. As the authors point out, it is best to consider here that if process and transformation seem to be progressive strategies, they are also essential neoliberal government techniques.

For reference collaborative work, see Robert Filliou’s Teaching and Learning as Performing Arts (1970, French translation 1998).

Cosmin Costinaş and Ana Janevski, eds., Is the Living Body the Last Thing Left Alive? (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2015).

Emma Bigé, “Nap-ins. Politiques de la sieste,” in Mathieu Bouvier, ed., pour un atlas des figures, digital project (Lausanne: La Manufacture – Haute école des arts de la scène, 2018), see https://www.pourunatlasdesfigures.net/element/nap-ins-politiques-de-la-sieste.

Marina Vishmidt, “Beneath the Atelier, the Desert: Critique, Institutional and Infrastructural” in Marion von Osten: Once We Were Artists (A BAK Critical Reader in Artists’ Practices), eds. Maria Hlavajova and Tom Holert (Utrecht: BAK, 2017), 220–221.

L’Assemblée des valeurs (The Values Assembly) was carried out by the contemporary art network BOTOX(S), with collaboration and support from Côte d’Azur University and the DRAC Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur. Following a series of filmed interviews with different art workers completed during the pandemic, this assembly invited us to collectively reflect on the values of contemporary art in their symbolic, social, economic, environmental, and even philosophical dimensions.

Started in the 1960s in the favelas in São Paulo, and later on adapted to other contexts, it is a form of interactive theater. A situation of oppression is the starting point, which is played over and over until a certain form of consensus is reached among the participants.

Irit Rogoff, “Becoming Research: The Way We Work Now,” conference at the Centre Pompidou in Paris as part of the public program for the exhibition “Cosmopolis #1: Collective Intelligence” in 2017.

Jérôme Dupeyrat, En grève, Art et conflit social (Toulouse : Éditions Lorelei, 2024), 42.

Florian Gaité, “Contre-performances. À propos de John Deneuve, Myriam Omar Awadi et Nicolas Puyjalon,” Le Quotidien de l’art, édition n° 2813 (April 2024).

Oswald de Andrade, “Anthropophagic Manifesto” (1928) (Paris: BlackJack éditions, 2011).

Flora Bouteille in conversation with the author, Pernod Ricard Foundation, Paris, February 21, 2024.

Andrew Hewitt, Social Choreography: Ideology as Performance in Dance and Everyday Movement (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2005), 17.

Oliver Marchart, Conflictual Aesthetics – Artistic Activism and the Public Sphere (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019), 177.

Marie Moreau in conversation with the author, April 11, 2024.

Didier Debaise, Isabelle Stengers, “ L’insistance des possibles. Pour un pragmatisme spéculatif ”, Multitudes, vol. 65, n° 4, 2016. (“The Insistence of Possibles : Towards a Speculative Pragmatism”, Parse Journal, Issue 7, 2017)

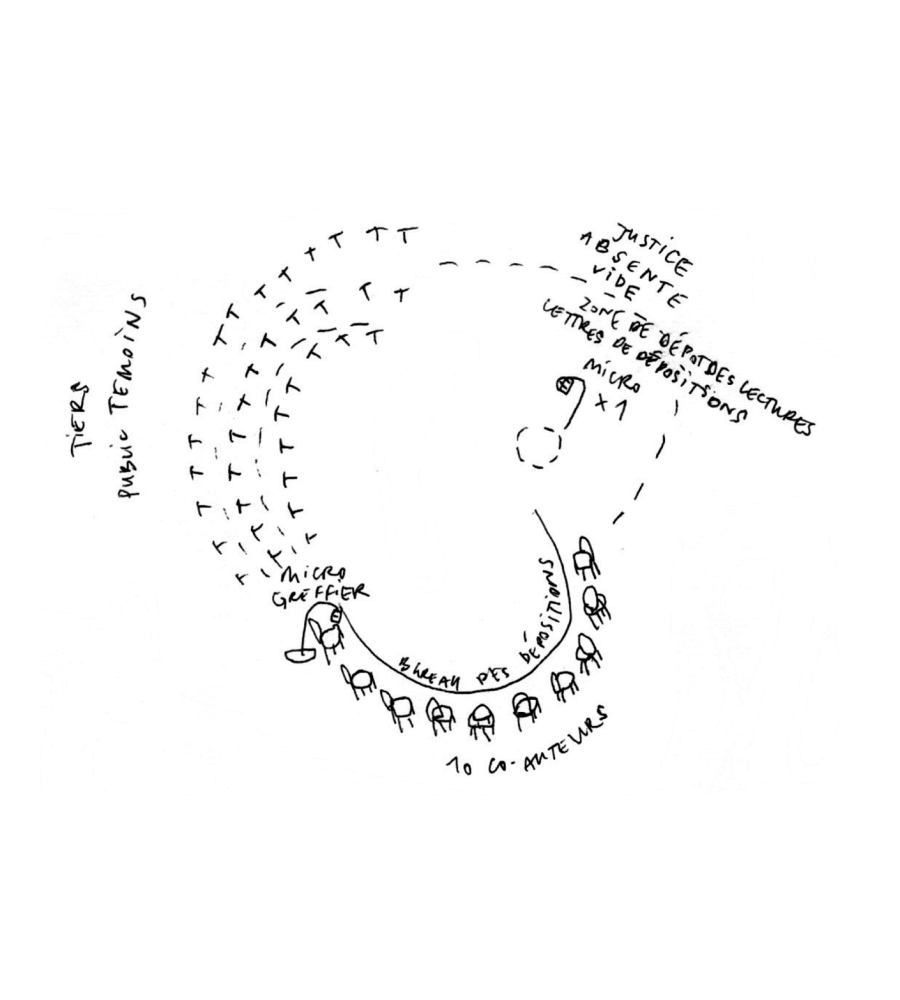

Marie Moreau and Sarah Mekdjian, “ Œuvrer une justice spéculative. Bureau des dépositions ”, Vacarme 89, hiver 2020, p. 119-131.

Cristelle Terroni, “Sur quoi opère l’art, entretien avec Franck Leibovici,” La Vie des idées (October 14, 2016).

In France, undocumented individuals can receive copyrights, ensuring that they are remunerated for their work.

Quoted from a document associated to “Minen kolotiri. Sculpter le droit par le droit.” performed in 2022. See https://iuga.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/institut/actualites/minen-kolotiri-sculpter-le-droit-par-le-droit-1134242.kjsp

Regional, Interdepartmental Direction for Economy, Employment, Work and Solidarity.

The artist in conversation with the author, May 5, 2024.

This workshop, conducted with Marina Stanimirovic, Lukas Wegwerth, Moritz Maria Karl and Christophe Machet, was conceived as part of the initiative “Les moyens du bord” (la Villette x Centre Pompidou, 2020).

Valeria Graziano, “Toward a Theory of Prefigurative Practices,” in Danjel Andersson, Mette Edvarsdsen and Mirten Spingberg, eds., Post-dance (Stockholm: MDT, 2017), 181.

Jilly Traganou, “Embodied Infrastructures: Rehearsing an ‘Otherwise’ Political Future,” Journal of Architectural Education, vol. 78, no. 1 (2024): 115–126.

This method was adopted in response to regulations prohibiting the use of conventional loudspeakers.

Ibid., 124.

Cette méthode a été mise en place en réponse à des réglementations interdisant l’utilisation de mégaphones conventionnels.

Ibid. p.124.