Conversations on art with Bertrand Dezoteux

The films of Bertrand Dezoteux teleport us into surreal worlds, but sometimes also into simple earthly landscapes like those of his native region of South West France, or into indistinct towns. Thus we roam heterogeneous, fantastical or real spaces, populated by digital, human, animal or hybrid creatures of all kinds. But if the artist is exploring the unlimited virtualities of 3D and taking us on interstellar journeys, he never loses sight of Earth and earth.

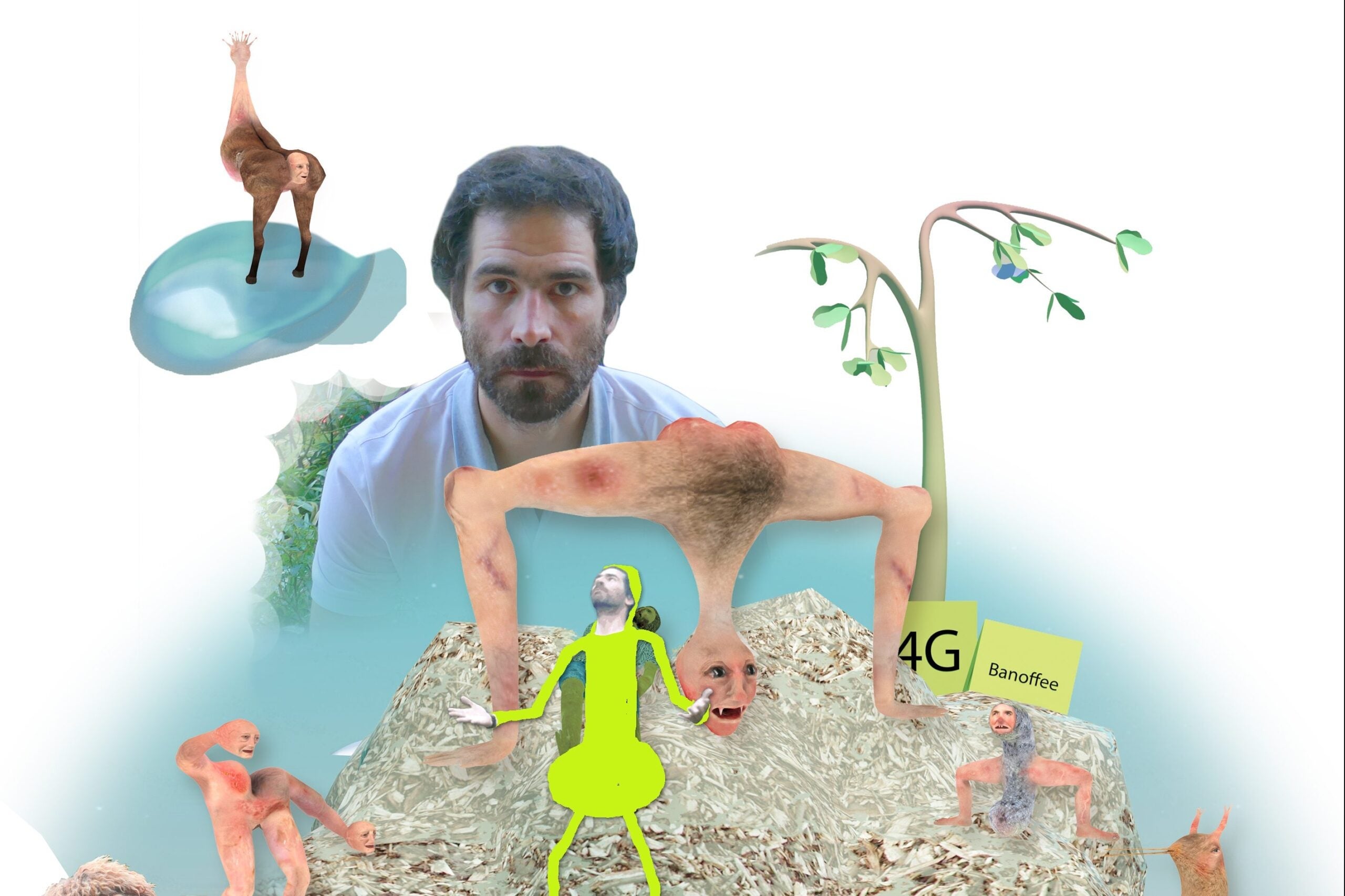

The artist explores contemporary image techniques, being something of an ethnographer of the customs and tools of highly codified universes. Like entertainment industry productions, with which he shares the same tools, Dezoteux creates fantastic worlds, but breaks the codes of the genres he examines, particularly fantasy, SF, video games and advertising. His films render genres “delirious”, pulling them in several narrative and visual, cosmic and earthly, supernatural and realistic directions. The artist builds composite worlds that combine different techniques like 3D, video, photography, CGI and real appropriations, borrowing their varied references to mass, pop and scholarly culture, to the history of art or to traditional folklore. In The History of France in 3D “from the dinosaurs to the eighties”, we ride a high-speed train at full throttle through magical lands, in the company of Roland Barthes, Jules Michelet and Christopher Columbus, to whom the artist lends the voice and words of Charles de Gaulle or Michel Rocard. His aesthetic is mixed and hybrid, the product of assemblage. Although his universe is deliberately surrealist, he can abruptly shift into observational documentary, or conversely, when the artist is filming reality, the fantastical can loom up. Evoking the coming-of-age fable, his films get us lost in sidereal labyrinths, abandoning us in backwaters full of all sorts of bathing monsters that take after Bosch and quote Picasso (Picasso Land). In fact, his films immerse us in metaphorical environments of sight and sound. The CGI horse that leads the film Zootrope speaks with the voice of a real little girl who explains her love of animals.

Guided by experimentation and play, Dezouteux’s art proceeds from DIY. He is a digital do-it-yourselfer who takes advantage of his tools’ potentialities, or their limitations, but he is also a 21st-century image-maker. His images vary depending on the subject: the can be precise and naïve, in the style of medieval illumination (Harmonie), or efficient like a 3D demo, or raw like home video, or all of this together and many other things besides… The artist gets different kinds of technique and imagery to play with or against one another, making low-tech use of high-tech, multiplying the slick or cheap-looking effects of textures, superimpositions, special effects, etc. His works are wild yet efficient machineries, subject to the fortuity of 3D’s everything-is-possible, and therefore to unlimited imagination.

Dezoteux naturalises the supernatural, by various means, like video or photography, but one of the most powerful means is the use of real voices, usually endowed with the accent of South-West France. If sound is an integral part of his film work, the artist is sensitive to vernacular language, which expresses an individual, a territory, a community, an era, and trivially real life. The incongruous incorporation of those personal and local voices into high-tech images re-territorialises a standard, impersonal aesthetic that seems to come from the “desert of reality”. This operation is characteristic of Dezoteux’s art, humour and straightforward funniness. Endymion, a family story and intergalactic car journey, brings together grandmother, father and son in conversation, each pursuing his or her idea. This is how they get along and communicate. They are the voices of his grandmother, his father, and himself the son, which he recorded, ultimately building a family archive. Against a starlit sky, the grandmother recounts, with the singsong accent of the South-West, her metaphysical dizziness at the idea that the earth is floating in an infinite universe, and that we are ultimately walking over, indeed within, a sidereal void.

The artist himself tackles another entropic, infinitely-expanding universe that is just as dizzying: our visual environment all over the world. Quoting Jean-Christophe Averty (one can see the kinship that our artist shares with the brilliant TV and radio man), he expresses his “desire to awaken people from their usual torpor, from that image slop which that bellyful of shit is constantly spewing”.

Anne Bonnin March 2021