RED CLASSIC / RED FIGURE

A solo exhibition of Robert Huot

Robert Huot’s Red Classic/Red Figure exhibit features a collaborative series of nude self-portrait photographs undertaken by Huot and his late wife, Carol Kinne. Huot and Kinne took their initial inspiration from a reading of Kenneth Clarke’s The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. While surveying the history of nude depictions across several media and spanning more than two millennia, they revisited the regular recurrence of themes and poses, dating back to the early Greeks and Romans, that had been revived in the Renaissance and continually ever since. What they saw was the system of images embedded in the very foundation of our ideas about beauty, the images from which we draw all our assumptions about the ideal human form. But as the artists were in their seventies and sixties, respectively, what they did not see were bodies that resembled their own. The few classical works depicting elderly citizens tended to portray them in a pathetic light, but when the subject turned to the ideals of beauty, only youthful bodies remained in evidence.

In an age when almost any depiction of nudity already carries a certain amount of political baggage, Huot is more concerned here with the politics of ageism. To what extent is it possible to countermand this pervasive erasure of the aged human body? And who is authorized to contribute to the definition of our corporeal ideals? As two lifelong painters, Huot and Kinne felt they held their own share of the right to this imagery, and that it was up to them to hijack it back, and challenge the ancient Greek notion that beauty was the exclusive property of the young. How could it be? When even our most basic ideas about it are thousands of years old? Here, these two artists were ostensibly looking at the entire history of beauty, but finding no reflection of the beauty they still saw in each other, or of the desire they still aroused in each other in the all-too-real world. In response, they created this series which brings the immortality of imagery into confrontation with the mortality of the body, and in so doing reminds us that Greece itself, and its ideals, are no longer young. While many of these compositions will be familiar to the viewer, the photographs nevertheless stand on their own power, and pose their own new set of vital questions.

Huot has said that it would be a shame if these images were perceived as sen- sationalism. And indeed why would they be? The display of his and his wife’s bodies is intended as a statement of fact. It is a documentation of real human beings who are still seeing, experiencing, sharing, and thinking about beauty. The photos were taken in the home the couple shared, using only natural light, and have been printed at almost life size, without any editing or retouching. The power in these images emits directly from the conversation between the models’ bodies and the contexts in which they are shown, casting our assumptions about each into mutual relief. Why should we be shocked at the vision of older bodies, jux- taposed with the archetypal scenes into which we so regularly project our fondest gaze? Unless, of course, that juxtaposition points to an unexamined and uncomfortable corner of the collective narrative, shining a light that draws a chiaroscuro line along the shape of our own denial. What is it that lurks in the darkness from which these figures emerge?

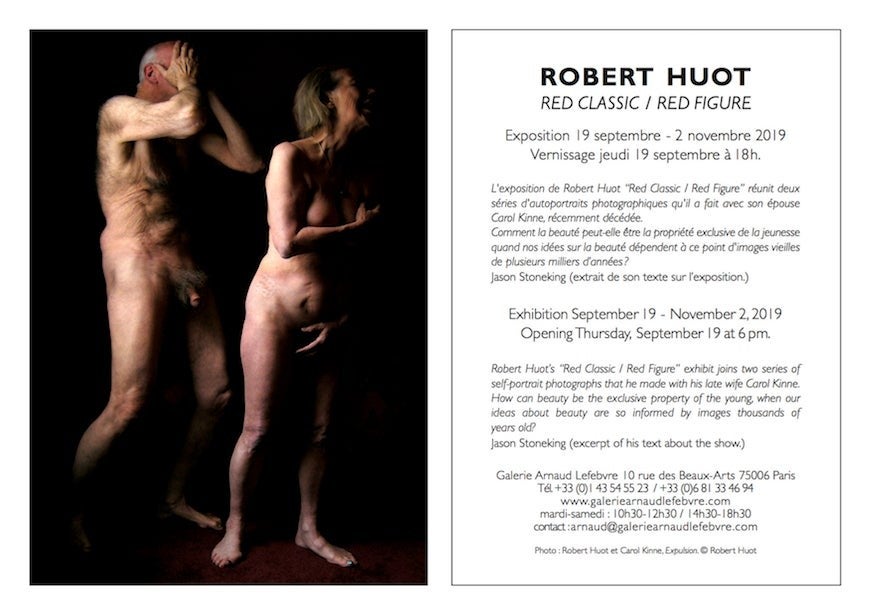

The appearance of fragile, delicate, mortal flesh, expressing its form as an identity against the backdrop of the void, is a testimony of the timeless natural story. The one that dates back to pre-Christian imagery, the one that dates back to before any imagery, the one born in the fundament of the universe, unspooling its pagan pageantry into the earth, the sky, the seasons, and the whole wealth of mystery to be found in all the cycles of life. These photographs reach back into that fertile and undefined time. Into the history of the eternal spark. Into the myths of our origin. And thus they question the earliest depictions of humanity, and of life figh- ting its way free of the boundless dark. The centerpiece of the show is a large portrait of the two artists together that recalls the expulsion of the first couple from the garden of Eden. Huot covers his face, and Kinne covers her breast and pelvis, both of them averting their eyes in anguish as they exit the scene into a foreboding blackness. But from what have this humanist Adam and Eve been expulsed? From youth? From participation in beauty? From life itself? And of what, if anything, should they be ashamed?

If beauty is to be found in beholding the triumph of life, then it depends on our expanding understanding of what feeling alive is supposed to look like. After their two long lifetimes of seeing and making things to be seen, these artists refused to be banished, pushed aside, forced into retirement. They refused to sim- ply cover themselves, medicate themselves, and quietly slip away to the tune of our blissful ignorance. They refused to obey the ultimate prescription. And their mutinous vitality is a glorious act of defiance, made all the more poignant by Kinne’s recent passing. This last creative gesture that they shared is a liberating reminder that nobody owns beauty. In an art world whose head is so quickly turned by the hot new thing, and in a universe that blinks us out of existence with such terrifying certainty that we are constantly tempted to look away, Ro- bert Huot and Carol Kinne are still looking, and inviting us to look with them, both back into the long history of our beauty ideals and ahead into the future that awaits all our mortal bodies.

Jason Stoneking