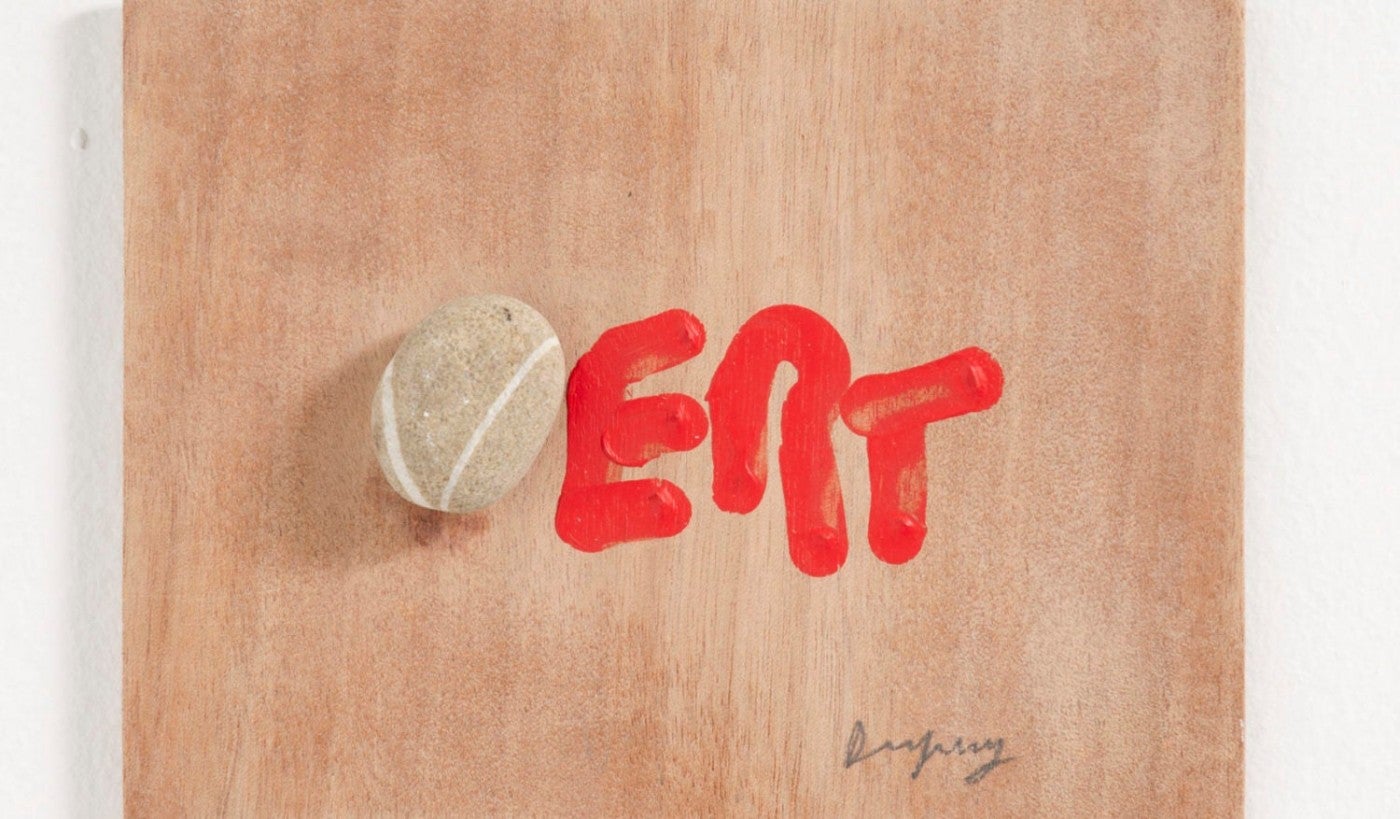

Oh ! What ? Here.

Jean Dupuy solo show.

Facetious and discreet as they may sometimes be, all the stones exhibited here, which come from Puerto Rico, from the bed of the Adige in Verona, from the Plage des Anglais in Nice, from Pierrefeu and from all sorts of other places, speak of the way in which water and the gaze both contribute to the same creative ecology. Water takes the hard edges off salient rocks, hollows the meanders of their softer parts. It polishes and polishes and turns their veins into letters (o, x, i, c, v, q all higgledy-piggledy), signs and scores, and reveals, as if in a silver bath, the silhouettes of animals and grotesque that

the pareidologist Dupuy examines with his magnifying glass. These discreet works are important because they transform this gesture of gleaning that we have all performed (who has never found in their pocket a pebble whose banality sparkles with promise?) into a haiku of stone.

One might think that Jean Dupuy and Roger Caillois shared an analogous love of stones, but the richness of the Ypudu stones lies precisely in their absence of the exceptional. They are pebbles of no value, rolled stones that enrol language. The worn pebble “lets all the sea pass across it,” writes Francis Ponge. The pebble lets pass all words, including exclamations of surprise: Oh! What? Here.

The second part of this new exhibition by Jean Dupuy at Galerie Loevenbruck presents the anagrams that are systematically associated with each work. The display plays a score over two horizons, the material (stones) and the linguistic (anagrams). Except that language is part of the material (the letters in the stones) and the material part of language (the text is materially embodied on paper and in the colour of the letters). If, in Dupuy’s work, the anagram acts as a poetic commentary with a careful, arithmetically measured rhythm, then over time these earthy little frenzies of language have become pure reductions, written stones, the work of patience, in which only the

essential remains. “The simplest things are the most difficult to do,” he points out. “What is short reads more quickly, too.”

Like a smooth-skulled pebble, it is in his character to say what is obvious but not so easy to say. It is in his character to say what is easy to say but not so easy to do. “Trying to imagine the time it has taken nature to write these figures makes my head spin,” we read in one of his anagrams.

Now aged ninety-three, Jean Dupuy entered history long ago. And yet he is as light as the air he hums. “The rest is not very important,” he adds.

What Jean Dupuy’s stones say is that the found pebble is magical because it is potentially the inexhaustible expression of language. That is important. It is a talisman. It is the art of joy.

Pierre Baumann, Stones. Jean Dupuy, March 2019