1.

“I am not a woman.”1 I spied the sticker on Fabienne Audéoud’s refrigerator as we were saying our goodbyes at the very end of our studio visit. The kitchen was tidy and lived-in. A bowl of red onions stood on a worn wooden table covered in cables and notes, facing out onto the main studio area which had been converted into a viewing room for the occasion. A breeze issued in from a door that opened onto a generous roof terrace, where we had been standing a minute ago, admiring the view over Paris. When I pointed out the sticker, repeating the phrase out loud, Audéoud seemed bashful. It was certainly a statement, she explained. A statement that spoke back to her because, she said, she realized she had never felt much attached to that identifier: Woman.

Detachment is the opposite of hatred. Renouncing the label of ‘woman’ is not a misogynistic act. I could relate to Audéoud’s feeling: the sense that gender was an artefact you could inspect; an article of clothing that you could put on and feel momentarily changed by. But it was the bold declaration that made me jump. Audéoud has an affection for slogans which, at first blush, may seem combative. In-your-face. Statements so confident that they seem to demand disagreement. Yet, to Audéoud, they are more like problems or propositions. Questions without question marks. Provocation without aggression. Vulnerability without pity. That is Audéoud’s affective style. “I’ve got this problem with language, it’s complicated for me when you have to make a jump between what it says and what it's supposed to mean,” she explains.

I had first seen Audéoud’s work years ago, on the iPhone screen of a friend who had flirtatiously drawled: you’ll love it. Soon, we were scrolling through luminous photographs of bootleg perfume bottles, the kind one would find at a night-market or convenience stores. Words emblazoned on the outside seemed, to me, like love spells or money spells for the wearer. There were phrases that spoke to outrageous aspiration (“New King,” “Rich Man,” “Chairman”) and realistic sleaze (“Dangerous Swamp”). And there were phrases that evoked the powerful, illogical state (“Insanity,” “Instruction,” “Full Release”) that even high-budget perfume ads sought to achieve, in attempting to visually or linguistically represent the senseless allure of fragrance. Audéoud had bought each bottle for under five Euros, in her working-class neighborhood of the 18th arrondissement, or abroad. She displayed them in clusters, on plinths, or individually, on shelves—doing the readymade trick to illuminate the poetry hidden in plain sight. Arranged together, the glass bottles became poems of capital; poems of insecurity and reassurance. Poems that she titled without euphemism: Perfumes For the Poor (2011-24).

Perfumes for the poor are artifacts for losers. They are not objects of luxury, but rather imitations that become invocations for future windfalls. They are purchased promises that a shift in attitude and swagger will alter unfavorable circumstances. They convey the idea that smelling like money will help you make it. What I am describing could be applied to any lifestyle product, not only cheap perfume. The propulsive gap between ideal and reality fires up the engine of consumption. “The figure of the loser in the femininity context is not just one I find sympathetic — she is crucial to me,” writes Virginie Despentes in King Kong Theory (2011). In a forceful litany, she describes the myriad ways a woman can ‘lose’ — through being too feminine, through being not feminine enough, through being weak or too tough, too susceptible or too unfeeling—and the myriad methods that will supposedly help her avoid losing. Beautification, wealth, pandering to men, turning the other cheek to violence. Taking it until you can’t take it anymore. ‘The loser,’ as a figure, is also crucial to Audéoud, because — as per Despentes — the winner does not exist.

2.

Say that you are the prettiest woman of them all until you believe it. Once you believe it, the logic goes, you will become it.

The winner does not exist, which does not stop us from wanting to become her. With the fervor of a teenager seeking tutelage on Youtube, I watch Audéoud’s early works over and over, especially Je suis la plus belle des femmes (2000). The video features a close-up shot of Audéoud repeating the phrase until the words and sounds break down, in what will become a signature technique of her performances. There is a rhythm to the breakdown, a freedom that arises from the disarticulation of a simple structure that was once taken for granted. “It was like punk, but without the beat, right, interesting, without a regular rhythm, completely free, completely crazy music,” says Audéoud about her early exposure to London’s improvised music scene, which had seeded her interest in performance to begin with. “And I suppose it's the only music which hasn't been reused or re-formatted. It’s still there: completely useless for useless.” With the incantation of charged phrases, the early performances resemble the ‘manifestation’ videos that pop up all over social media, where positive affirmations play on loop either above or below music; that is, on either a conscious or subconscious broadcast2. The belief is that enough repetition will ‘shift reality’ for the viewer. The act is close enough to prayer — where repeating a certain phrase or gesture brings the religious supplicant closer to god — though the concerns are totally mortal. Manifest a slimmer nose, a better career, good grades or a date with your crush. Say that you are the prettiest woman of them all until you believe it. Once you believe it, the logic goes, you will become it.

The wish that feminine exceptionalism will bring about blessings and protection is exactly that — a fanciful, forceful delusion. “It’s only when I stop trying to speak that I can perform the traditional ideals of beauty, thus illustrating the oldish French phrase “sois belle et tais-toi” meaning ‘shut up and look good,” she says of Je suis la plus belle, well aware that, under the regime of gender, both visibility and invisibility are force-multipliers of vulnerability. The price of losing is steep — and because every woman is a loser, we are always paying it out. That same year, Audéoud presented the video work She Prepared the Staging of Her Death (2000), before she actually staged her own death in John Russell Kills Fabienne Audéoud In The Style Of William Burroughs (2000). The audience, she recalls, was not aware of what would transpire. There was no trailer, no teaser, and only a trigger warning about high volume. Russell, a male friend and fellow artist, was to shoot her with a prop gun as soon as everyone was settled. The work was a comment on the apparent normalization of femicide in the art world. It was a reality Audéoud wanted to access, even though she did not “want to talk about it” in a direct or didactic manner. Together, she and Russell had decided to restage the murder of Joan Vollmer, the “nucleus” of the Beat generation, by William Burroughs, to whom she was married. Burroughs had shot her between the eyes. It was pure showmanship. He had aimed for the glass she had balanced on her head, in the style of William Tell and the apple. Audéoud had been considering both the glibness of his actions and his invulnerability to consequence. “He never gets convicted,” she says next to me on the studio sofa. “Burroughs kills his wife and enjoys his fame.” She presses play. Immediately, I hear the buzz of the crowd that fills the artist-run space in Brixton named Trade Apartment — loud, already inebriated, milling about as they wait for the performance to begin. Audéoud is sitting on a sofa on one side of the room, Russell on the other. They had set up three static cameras to capture the performance. These three views were then edited down into the documentation we were watching. Audéoud and Russell had paid close attention to believability. It was absolutely crucial that they shook their audience to the core. “We learned that it was really about the sound of it,” she says. “We had a small bomb in a bin, so the noise was really loud. And you can’t really hear it on camera, because the sound level is so high”—it just phases out of capture.

Fabienne Audéoud and John Russell, John Russell Kills Fabienne Audéoud In The Style Of William Burroughs, 3 screen installation showing the documentation of the eponymous performance for “Cover Version”, Trade Apartment, London, 2000.

She played dead for over half an hour. They had forgotten to give Russell the cue to wrap it up, so the performance also became a work of endurance as Audéoud lay covered in fake blood, doing her best not to move. As the tape rolled, we carried on speaking about Audéoud’s curiosity about violence: the clarity of the act, and the ambiguity of the interpretation. The artist Ana Mendieta — who was allegedly killed by her husband the artist Carl Andre — once said: “I’m not interested in the formal qualities of my materials, but their emotional and sensual ones.” It is a statement I connect to one by the poet Anne Boyer, who wrote: “That pain is incommunicable is a lie in the face of the near-constant, trans-species, and universal communicability of pain.” A spectator who experiences the shock of witnessing pain or violence vicariously, feeling it rattle their nervous system or strike them in the gut, receives a transmission of ‘experience’ that exceeds symbolic messaging. That force is what Audéoud is interested in channeling, like lightning along a conducting rod, in her performances. That force, rather than shock for shock’s sake, or the restaging of history, or the blank repetition of gestures, which are aspects of performance art that Audéoud readily critiques over the course of our conversation. “I was never interested in just expressing myself,” she says. “I'm interested in what is created between the audience and what I bring to them in that moment.” In 2000, Audéoud was commissioned to transform her performance You Cannot Uplift the Poor by Telling Them to Be Rich (2000-22) into a video for the series ‘Deeply Buried’ at the South London Gallery, curated by the late Donna Lynas. What was once a performance of grievance against all of life’s difficulties was contorted into a threnody, honouring the unexpected and traumatizing death of her partner, Josef Kramhöller. Folded into a chair at a friend’s studio, filmed on video instead of performing live because she had to attend her partner’s funeral, Audéoud expresses grief as a form of immense and ancient power, and as the outpour of a highly specific intimacy—the howl one flays against the world when love, which should never die, is taken from us too soon.

3.

Face, body, dress, persona; a social group, an audience, their reactions: these are as malleable as any raw material.

If you say it enough, it will become true. Practice positive self-talk in the mirror. Stand straighter, pay attention to your gestures. Repeat. Discipline yourself, and practice. Practice anything at all. Everything is a rehearsal for a ‘better self,’ who is supposed to emerge like a débutante at a ball, or a butterfly from its cocoon. Much of Audéoud’s practice applies both rehearsal and ‘delearning,’ finesse and undoing. In the video literally titled Practice (1998), Audéoud exercises a “hysteria of music composition,” performing a plethora of characters in a prolonged feat of breakdown and reassembly. In general, Audéoud repeats her performances over time, rearranging the sound, gesture, and affect over decades. The questions, without question marks, are eternal. Femininity, careerism, selfhood and other modes of social mobility become subjects to be studied intently and dissected. Dissection, if you think about it, requires a total mutilation of the subject. Only then can you achieve the detailed understanding that then leads to expertise. Watch Audéoud’s A Lecture on My Face (2000) and see it in action. Audéoud contorts her facial muscles, stretching her jaw and widening her eyes, pushing syllables out with an athletic violence, in order to convey something ulterior and fine-grained about the pain of incommunicability. “From this moment on, something changes so drastically that I am ‘looking at myself’ to try and understand… something,” she writes to me about the work, in a letter she sends before our meeting. A lecture on my face is based on the memory of what Audéoud had done after receiving a call from the police about Kramhöller. They declared that “something” had happened, but could not tell her specifics over the phone. As she waited for them to arrive, she did nothing but gaze in the mirror at her face with the strange hope that information would be revealed on the surface.

Face, body, dress, persona; a social group, an audience, their reactions: these are as malleable as any raw material. In her 2024 zine Gender Synthesis, the theorist Maya B. Kronic considers the practice of ‘gender pragmatism’: the commitment to understanding gender that can only arise from play-testing appearance, persona, and selfhood out in the world. “No-one knows what gender is,” she asserts3. Seeing gender as a construct does not condemn it to the category of purely abstract or immaterial. Instead, ‘gender pragmatism’ urges us to see everything about gender as material and therefore open to alteration. “You rig yourself up and you exhibit yourself through the technological infrastructure,” writes Kronic, who uses operational terms like ‘rigging’ and ‘techniques’ to underscore how appearance, ornamentation and display are rigorous and substantive ‘technologies of the self’ that interact with other, more generally-accepted ‘technologies’.

Fabienne Audéoud demonstrates how the scrambled codes of gender and language are utterly synthetic.

In 2017, at La Salle de bains, Audéoud displayed soft sculptures draped over a mannequin and hung on a suite of abstract paintings, made of thrifted and purchased clothing that was embroidered or defaced with Audéoud’s slogans. “I took great pleasure in developing my taste,” said Audéoud on the occasion of the exhibition. “I chose the garments for their styles, cuts, the quality of their fabric.”4 In The Jumper Shop (2021), she staged a performance, an opera, and an exhibition all within a retail space where visitors could purchase tasteful garments on display. Worn out, chewed up, shrunk and full of holes, yet made of fine fabrics and sold as art objects, they convey Audéoud’s playfully cynical attitude towards even the timeless and trend-free elements of fashion’s heavy symbolism. The ‘quiet luxury’ that appeals to the smart set becomes a hushed joke, as ‘power dressing’ does in Les petits mecs (2022), which features tiny mannequins dressed in CEO-worthy suits. The punchline mutates further, in Audéoud’s latest film, Battle of the Beige (2024) — an abstracted science fiction film developed on Runway, a generative AI tool for moving image — that takes the Burberry trenchcoat as its symbolic starting point. Humanoid figures smear into each other, into weaponry and desert hellscapes. At times, the figures become indiscernible beyond the iconic tan trench. The uniform itself becomes rhyme and reason for a future war that otherwise dissolves into nonsense. Because of the Runway guidelines, the film does not depict any actual violence.

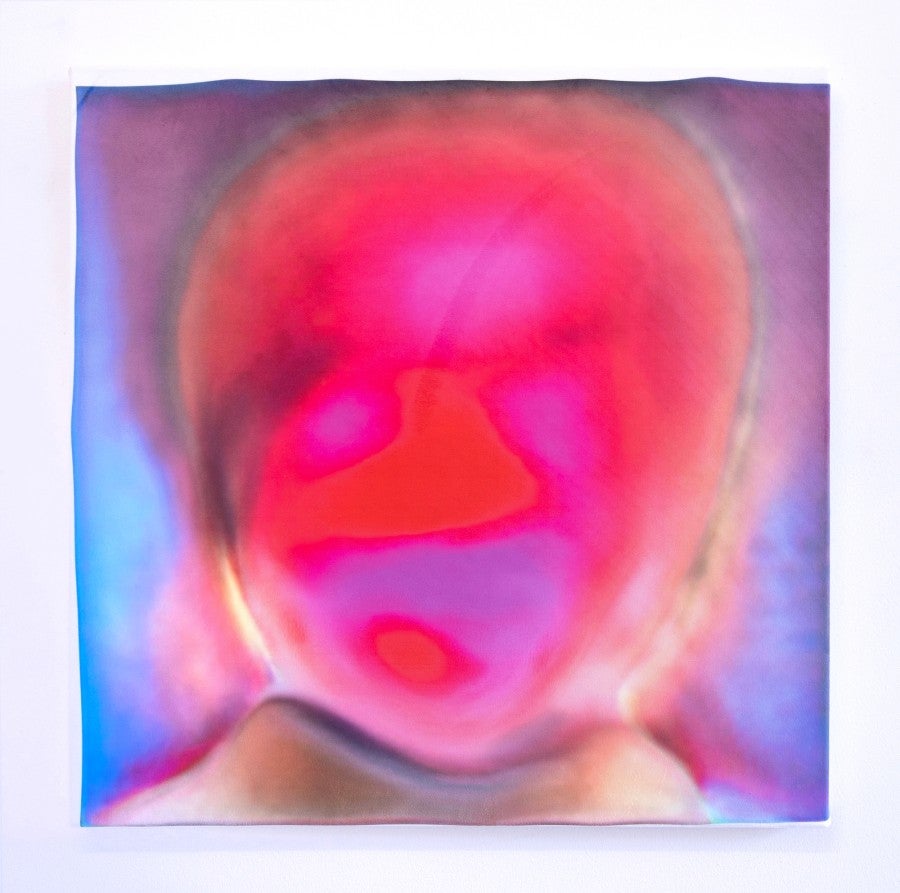

Under the banner of cyberfeminism, bodies and gender are as alterable as machines, and are always constructed in conversation with the world and its industries. In other words, there is no natural state, and every aspect of representing oneself is up for further experimentation, as Kronic affirms in ‘Gender Synthesis’—a positioning that informs Audéoud’s other engagements with AI, titled I Am Not a Woman (2023). In a series of prints on velvet, Audéoud uses a facial imaging programme to create alien figures that are simply human faces with their defining features ‘maxed out.’ She was interested in the categories that made a vast and diverse range of human faces legible to machine vision. Socially or aesthetically complex elements, such as how certain features were allocated to particular races or genders, were reduced to simple on-screen toggles. The work follows earlier experimentations with generative AI and other digital tools, which enabled her to morph and free-associate images similarly to how she would find music “without a beat, without a regular rhythm,” using these tools to blend and extend human body parts until they became unrecognizable. In one, a pornographic image is meshed with a frog; a clitoris becomes an iridescent pearl; and so on.

What would it feel like, to disarticulate and free myself from my first worldly designation?

Audéoud and I took a moment with the title of another suite of works created with John Russell, which feature smeared and disfigured bodies rendered in paint. Pourquoi les femmes aiment-elles l’enfer? (2005) is a joke I didn’t quite get because of cultural differences. We batted the phrase back and forth, enjoying what was revealed through misunderstanding, and I thought back to Audéoud’s very first point, the truck she had with language that did not actually convey what it meant. The way she used both directness and deconstruction to diffuse certain statements’ malefic power. “I was diagnosed late as on the autism spectrum, but before that I really could not understand why people would not understand things like I did. For me, certain phrases carry an extreme violence,” she says. She describes the early days of her practice, when she programmed an electric organ to play back staples of vocal sounds she’d reduced down from words. “I would sample words, stretch them, and turn them into instrumental sounds, and then I would feel quite okay. It's not the musicality of words that get to me. It's the meaning — how language performs. What it does to you or to the group.” In the past, she has referred to language as a virus which colonizes every surface and every state—a concept that originates with Burroughs, possessing malefic power itself5.

I ask her how it feels to restage her performances as time goes on, whether it has the same effect as sampling and stretching to make meaning malleable, and re-charge similar forms with new sensation or memory. “Completely — You Cannot Uplift the Poor (...) is not a mourning piece anymore. It is just one note, and no words coming out of my mouth. Sometimes you hear pleasure. We have to find meaning in expression — what do I express? I’m just singing one note. There’s not even a melody, no rhythm, no nothing, nothing more than one note, but sometimes people in the audience cry when I do it.” Audéoud was raised in an evangelical sect, her early experiences of the world soundtracked by others’ religious rapture—the trances and glossolalia arising from heightened spiritual states. In our conversation, she connects her lifelong practice of ‘minimal opera’ with a fresh interest in trance-like experience. Most recently, she was trained in self-induced cognitive trance. Moving between this world and the next is not a peaceful act. There can be screaming and, on rare occasions, vomiting. Crying and whimpers of joy, ecstasy, and terror are par for the course when one is in the process of psychic transformation. I considered what it meant for Audéoud to situate herself in a group pursuing this end so intentionally, to break reality surrounded by others who are equally focused on reaching an altered state through their own behaviour and utterances. Etymologically, to transcend means to go across, to climb. It is a surprisingly active word for something that, to me, feels more like the moment an airplane stabilises after takeoff, breaking into the silence above the turbulent cloud layer. Yet focusing on the action that achieves release from mortal limitations—rather than the relief that follows, or the limitations themselves—is exactly right for understanding Audéoud’s practice.

Audéoud’s body of work spans decades, and there are myriad ways one might taxonomise her prolific output. I would create a cluster under class, survival, and deception; a cluster under performance, the stage, and its history; and a cluster under the body, and what it means to live in one that might telegraph a message to the world quite removed from one’s self-concept. “It is a foundation stone of who I am as a writer, as a woman who is no longer quite a woman,” writes Despentes, of the loser state. “It is what simultaneously disfigures me and makes me whole.” I return to the phrase, looking at the acidic prints that comprise I Am Not A Woman (2023) and repeating the words back to myself. What would it feel like, to disarticulate and free myself from my first worldly designation? What would remain, and what more could be generated? In a wilderness of empty slogans and the beguiling accouterments of fashion and commerce, where self-design can both convey and detract from power, Audéoud taps the vein of emotion — the ‘pure affect’ that thrums below category and identity, below costume, skill and performance. Even when the only apparatus is her own body, her voice and her face, Fabienne Audéoud demonstrates how the scrambled codes of gender and language are utterly synthetic. That which simultaneously disfigures us and makes us whole.

From the sticker series commissioned by Cocotte, 2023. See https://cocotte.co/stickers.html

See, for example: ‘I Manifested My Life on Tiktok,’ BBC Three, 15 September 2020.

Kronic, Maya B. Gender Synthesis. Self-published zine, 2024.

René-Worms, Georgia. “Interview with Fabienne Audéoud.” La Belle Revue, 2017. See https://labellerevue.org/en/exhibition-reviews/2017-bis/fabienne-audeoud

“My general theory since 1971 has been that the Word is literally a virus, and that it has not been recognized as such because it has achieved a state of relatively stable symbiosis with its human host; that is to say, the Word Virus (the Other Half) has established itself so firmly as an accepted part of the human organism that it can now sneer at gangster viruses like smallpox and turn them in to the Pasteur Institute. But the Word clearly bears the single identifying feature of virus: it is an organism with no internal function other than to replicate itself.” Burroughs, W. S. (1986) The Adding Machine: Selected Essays. New York: Arcade Publishing.