News from Home (Some Epistolary Exposures and Passages of Ambient Paranoia for Mimosa)

Los Angeles is burning, hot pink and toxic. In the images of my childhood city that I look at from my laptop in Athens, its liquid cars and matte rooftops and attenuated palms are coated a sickly chemical pink—monochrome and almost fluorescent—from the flame retardant spilled in aerial flows from above. The city a furnace, firing and oxidizing its objects to a pink glaze. The lurid color rhymes with the covers of Mimosa Echard’s various books and zines that are glowing on my desk: the dark pink screen of Sporal, glitching and quilted; the soft-focus blanket, strewn with flora, covering Mauve Dose.1 Big pink vibes, dystopian and cogent, princessy and pharmacological. Or so I delineate some chromatic correspondence between artist and ecocide, personal palette and aesthetic of apocalypse, the femme advertorial irony that strobes both. Or so I write to Mimosa in New York, where she is in residency:

Apologies for the silence. The fires in LA are closer than usual to my family. It's totally apocalyptic, fluorescent chemicals covering the bungalows that haven't burned yet—almost the same color as your pink Sporal book. I've been thinking these days about my California childhood—its fire and flood seasons, its materials and chemicals, its on and off the gridness—and how it chimes with your childhood in France. How you were also raised away from consumerism, with a different kind of materialism, and how this attempt seems to worm its way into your work still. Does being in NY change the matter that you're attracted to? What are you gleaning from the city? In the US, we often confuse consumerism and materialism—or we did in California—but they're really not the same thing.2

Mimosa writes back:

I also thought about this chemical pink when I saw the pictures of the fire. I didn’t know that they used this pink stuff, I wondered why they had chosen such a weird color, and I learned it’s because “after a few days of exposure to sunlight, the color fades to earth tones.” I chose the color for the book because I knew people would hate it, it was a mean pink in a way. In NYC I have started to photograph the ginkgo leaves on the ground, their dispersion, their relation to the road, to cars, to petrol, to detritus, like an infinite yellow powder on the street. The ginkgo tree is the only tree that survived the atomic bomb in Japan. I thought it was quite beautiful that it is so present here. Taking some kind of poetic, sweet and slow revenge? Also the ginkgo tree has a very cool, ancient sexuality. Their reproductive systems are so ancient, before the seed, and they can switch genders… “La sexualité c’est une affaire de plante” quoting Proust, lol. Anyway, sex and the city! I want to make a big wall work made with different modular panels, I was so fascinated by the composition of the Tibetan mandalas in a show at the Met as well as the show on Siena. I want to mix a lot of processes, oxidization, collage, paranoid geometries…3

Gimme Shelter or Lies

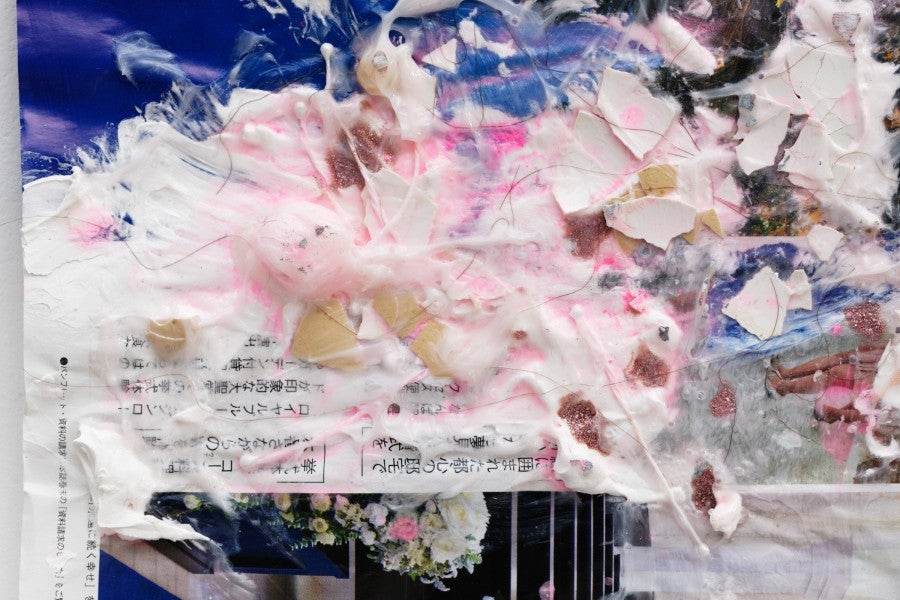

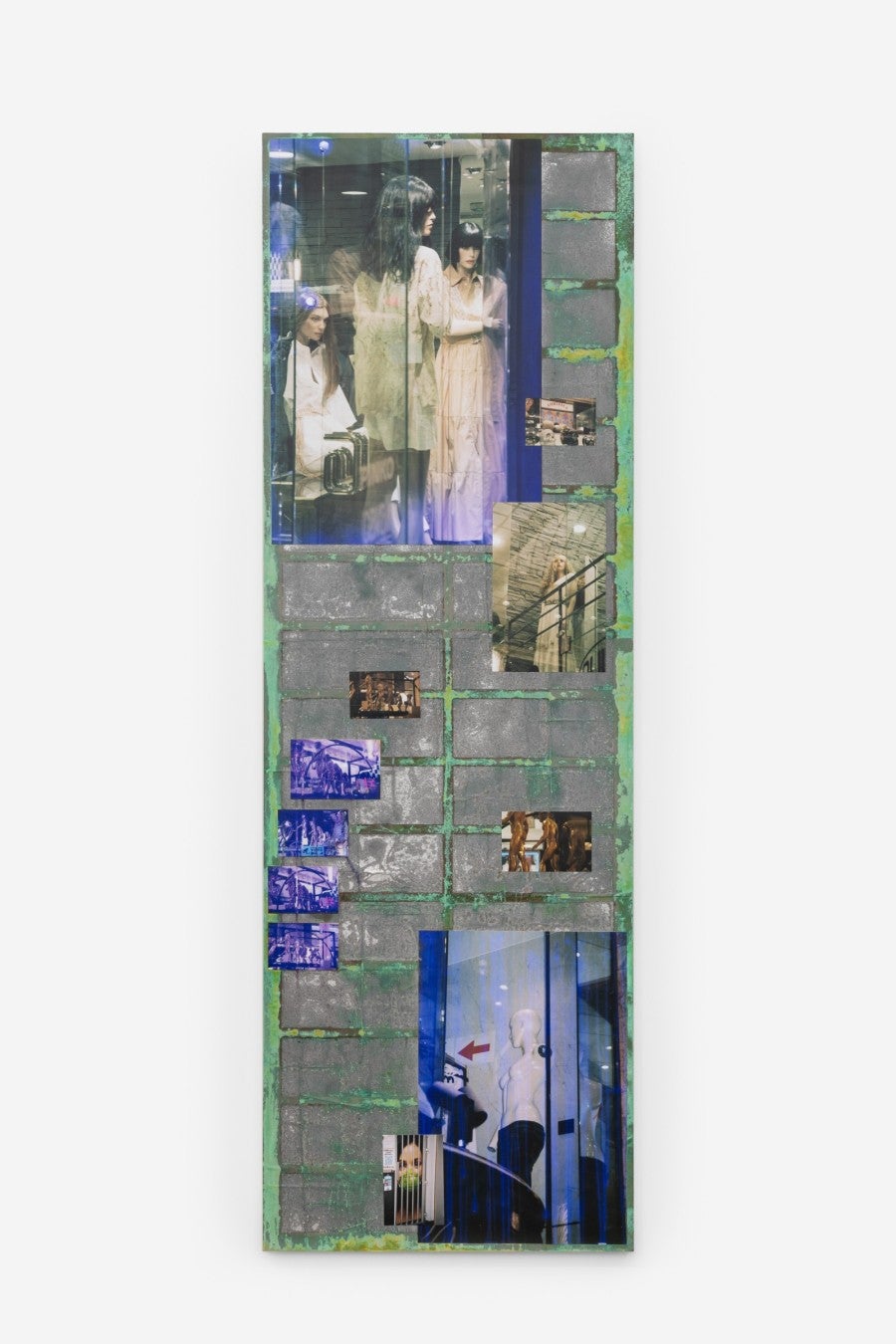

We move through her recent paintings as one might move through an arcade: protected, paranoid. Sheltered from what might come from above—acid rain, radioactive waves, atomic radiation, technocratic plunder, late-capital servitude, the equatorial drizzle of theory and literature, the hard rain of aesthetics and the ash of ecocide, cold love and its loss—as if by some glass-and-iron roof, protective paint or fabric. To pass through an image as though it were a passage. Architectural and yet more than a window—a multitude of frames. Unexposed “to the elements” and yet a visual regime of accumulating exposures. Within her images, we pass dead stock of cheap acrylics, cheap shoes, and city maps. We see mannequins haunting windows, actors statically signaling their lines, their silent meaning, like beacons. We are reminded of the mannequins in the plays of Tadeusz Kantor, transitional entities between object and actor. Or as Jan Kłossowicz once wrote: “Mannequins embody the metaphysical side of theater.”4

Like those mannequins, we are inside the paintings of Echard, or I am. Paintings embedded with photographs of a passage, that is, the Arcades des Champs Élysées, a kind of theatrical stage. Built in the twenties, exactly a century ago, the arcade’s previous acts were as a bathhouse and cabaret. Now, though, the arcade stages bodies consumed by retrograde image references and anxious distances traveled, scenes that suggest surveillance and tourism, flows of deracinated figures and imported waste, brought together by a kind of nonplace. That is, those sites of transitory anonymity in cities and ecologies on the brink, all projects unfinished and dissembling across the frames, the borders, like cheap goods and harassed bodies. Makers and consumers of images all, exposed and unexposed as we are.

Echard’s paintings offer variegated traces of chemical corrosion, architectural ideas of the social, and material histories of institutional mistrust.

Walter Benjamin called his own Arcades Project the “theater of all my conflicts.”5 Today, its unfinished collage of fragments and materials, images and ideas, suggests an unending cinematic montage. Thus we go, though, as across eras, their technologies and metaphors: from theater to film, live performance to the moving image. In his letter to Gershom Scholem, written on January 20, 1930, from Paris, Benjamin elaborated:

What I primarily want to talk about now is my book, Paris Arcades. I am truly sorry that a personal conversation is the only possible way to deal with anything having to do with this book—and, to tell you the truth, it is the theater of all my conflicts and all my ideas, which do not at all lend themselves to being expressed in correspondence … I have been held back, on the one hand, by the problem of documentation and, on the other hand, by that of metaphysics.6

Inside his theater of struggles was Benjamin’s image of an epoch. A kind of painting or window or mirror. “In the background of this theory of the historical image, constituent of a historical ‘mirror world,’ stands the idea of the monad.”7 That is, of some indivisible substance that reflects the order of the world and from which material properties are derived. The Arcades Project was, writes Susan Buck-Morss, “a presentation of history that would demythify the present.”8 What history, what present? One of emergent fascism, in Benjamin’s case, and of the reemergence of fascism, in Echard’s.

For it is impossible to consider Echard’s employment of the arcades without considering Benjamin’s project. Both being concerned with visual regimes and their technologies of collage, montage, and the fragmentary, all urbane flows of information as well as of bodies, and those that would control and exploit them. What orders of what world—sporal and ecocidal, conspiratorial and consumerist, technological and autocratic, holistic and aesthetic—is Echard devoting her own material and metaphysical theaters of conflicts and ideas? What properties does she derive from them? What mirror? What monad? What inheritance? Paranoid materials for Parisian passages, perhaps.

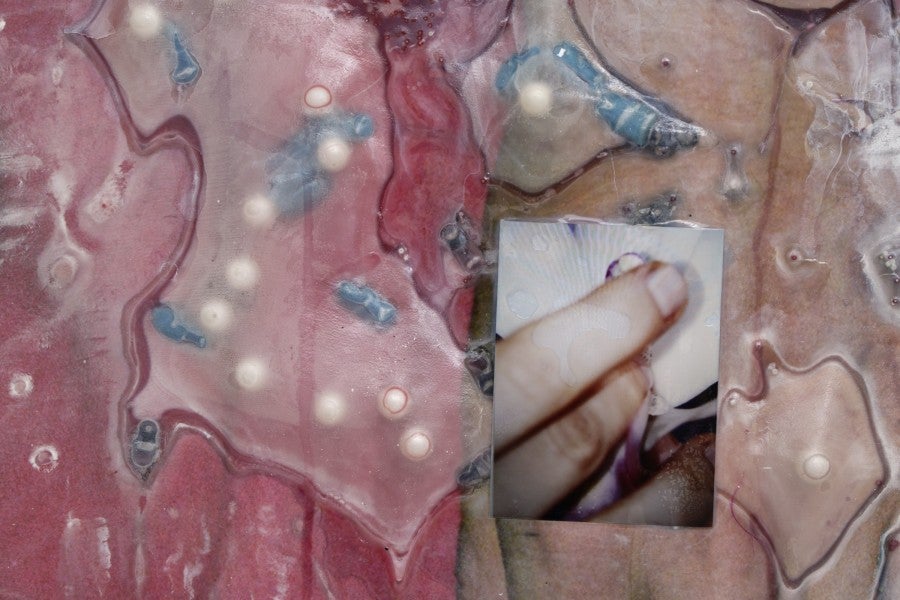

Echard’s paintings offer variegated traces of chemical corrosion, architectural ideas of the social, and material histories of institutional mistrust. The paintings feature grounds of electromagnetic shielding fabric, a conductive material used to create radiation-free enclosures (nuclear anxiety or 5G paranoia). Grids of aluminum foil and images of the arcades overlay them, poor copies or palimpsests. Finally, corrosive liquids are applied that patina the surfaces, bleeding green and silver. Her resulting oxidized tableaux are modular, systemic, cinematic, literary—both exposed and protected, conductive and corroded, all ambient suspicion and material maximalism. An anxiety of influence of the geological earth and its processes, her works are situated in the mineral ruins of the nineteenth century and electromagnetic motherboards of the twentieth and twenty-first.

To be exposed suggests both the vulnerable body—stripped of its defenses or its health or its lies—as well as the photographic image coming into being. To be exposed suggests some truth coming to light, just as it suggests the chemicals and light of the film exposure. What is exposed by light, figuratively? “Lies.”9 What is exposed by light, chemically? Images. All modular structure married to off-the-grid anxiety, some feminine consumerist language to a Pictures Generation-esque advertorial loop between desire and disillusionment, Echard’s libidinal paintings offer us vulnerable surfaces—shiny then corroded, metallic then matte—for permeable bodies. They enact a wish for protection: material transformation as talisman.

The flower of surface, blooming and dying, again and again. A kind of skin, delicate and exposed and eruptive—à fleur de peau. What else? The flower of fear, blooming and dying, again and again. The flower of reproduction, blooming and dying again and again. The flower of hope—like love—blooming and dying, again and again. The flowers of rust, some corrosion of iron oxide formed by the presence of water and oxygen. The flowers of patina, oxidation forming a thin green or brown surface film. Not of images, though. Something else.

Hotel des Mimosas

I have a friend who sends me iPhone pics of yellow Mimosa flowers whenever she encounters them. The images bloom inside my phone, some citrine code for attention. Mimosa pudica, I read, contains psychotropic agents that act as an anxiolytic (low doses) and a muscle relaxant (higher doses). Mimosa is also sensitive to stimuli, to exposure. Its leaflets turn inward when shaken, exposing their thorny stems as defense. But Mimosa is also called acacia. The botanist Carl Linnaeus first noted it down in 1773.

In 1982, Chantal Akerman was asked to direct a film workshop at INSAS, the Brussels film school. The resulting student film constellates the love triangles of a cheap hotel’s young guests and employees. They have come to the big city, Brussels, to look for jobs and love. There is a crisis in both. The hotel is called Hôtel des Acacias; the film, too.

The first weekend of December, I travel to Paris. Echard and I have lunch and then go to the Jeu de Paume to see the Akerman survey. We are both fans. The show is called Travelling, and it features Akerman’s film paraphernalia as well as films, Hôtel des Acacias, among them. A room of eighties-era monitors, boxy and black, features her footage from the Soviet East, each screen dominated by singular hue—blue, green, red—the documentary images flush with the fictive, the affective, the staged. In Hôtel des Acacias, the scenes are defiantly fictive, almost slapstick, the palette vivid and chromatic. A woman in a red dress and red hair stands at a red wall; a waitress in a blue blouse stands by a blue banquet; a young woman in floral waltzes in front of floral wallpaper; a blonde guy in tight yellow pants wears a skinny yellow tie. Color as idea. It ends with a ball, à la Austen, where the characters make up, break up, or flee. One of the guests disappears but leaves a letter, which is read out loud:

Dear friends: Because it’s really friends that I found here, I am leaving. I had come in search of love. I had come to find someone’s love. But what I found here is that everyone is lost looking for it. That’s what life is about. Always and everywhere. I thought my story was unique, that it was mine alone. I’ve grown up with it. And then I meet you all. And I was afraid. For you and for me. Love is always what you don’t have. I am leaving you forever. But I hope that no matter what happens, each of you will find a little happiness.10

But what is nature? It’s a question that Echard’s work seems to ask again and again, positing a world ecology as synthetic as it is biological, the transformative processes mimicking each other, as synthetic hormones often do.

Hôtel des Acacias feels like the younger, impoverished cousin of Akerman’s Golden Eighties, the 1986 musical set in a shopping mall that is one of Echard’s favorite films, she tells me, and a reference for her recent work. We watch it as well, the film’s stylized scenes offering alienated beauties in heavy make-up hoping to be noticed, loved. Arcades as early malls, I think, all transparent frames and smooth surfaces for the flows of bodies consumed with consumption, with visuality, with languages of desire and materiality, economies at once priceless and collapsing.

Echard and I spend hours in the Akerman show, then go have a drink. She takes me to a narrow bar with a completely red interior, the clientele mostly older, dissolute. The bar looks out of a Fassbinder film, or maybe an Akerman. I am wearing dark blue; Echard is in pink. We drink red wine and talk about Akerman’s eighties-era output and why musicals seem to be the genre of choice for moments of technocratic fascism. Weimar, the eighties, and now the present. We finish our drinks and I return to my pale hotel—all white walls, thin mirrors—to sleep.

The next morning we meet again and take the train into the suburbs, to her studio. It is a standalone wooden house evoking some seventies-era pastoral modernism. We look at her recent paintings and photographs and I clock the colors: pink, purple, green, brown, silver, bronze. Colors synthetic, feminine, and advertorial, or of mineral and metal. Hues of resources, natural and not. But what is nature? It’s a question that Echard’s work seems to ask again and again, positing a world ecology as synthetic as it is biological, the transformative processes mimicking each other, as synthetic hormones often do.

We talk about our hippy childhoods in California and France, full of amateur ceramics and natural foods, the withholding of screens and dolls by parents intent on dampening the consumerist or feminine drive. We discuss Echard’s films and zines, the digital and the analogue. Echard’s shelves overflow with plastic balls, mirrored beads, acrylic fabrics, pink boas, all the cheap, girlish-goulish charms of late capitalist trash in some femme adolescent aesthetic. Love is always what you don’t have.

Echard recently installed a public sculpture on top of a 5G mast antenna in Toulouse. She somehow got permission to use it and covered it with images of foxglove flowers, an enormous aluminum charm of a heart, and an LED screen that plays her personal videos on loop. She called it Lady’s Glove (2024), said it was a kind of anti-monument. That growing up, as she did, in New Age environs, antennas were the devil. She had, I saw, cut that image with another kind: something sweet and feminine, yet scaled up so that the cuteness became overpowering, like some female-presenting beacon surveilling the city. The devil is in the details.

I looked again at the gold and silver foils Echard used for her paintings, offering protection from electromagnetic rays, then at the arcade photographs of mannequins baked into their surfaces. The slim, attenuated figures might be characters in Hotel des Mimosas, at once alienated and artificial, between objects and actors, each giving anachronistic glamour, signaling pathos and bathos both. They are beacons of some localized signal, all material language and deafening static. Karen Barad once wrote of the machinations of power, its material constraints: “The body reacts to the forces, manifest as shifting material alignments and changes in potential, and becomes not simply the receiver but also the transmitter or local source of the signal or sign that operates through it.”11

Trances of Fossils

In late January, while LA is still burning, I go to the Peloponnesus to visit the ancient archaeological sites of Mycenae and Messene. In Mycenae, I stand in front of the lions’ gate where Clytemnestra had Cassandra assassinated. In Messene, I touch the cold colonnades, tracked with fossilized vegetal trails of an ancient herbarium. The pale mineral bodies dressed now in foliate motifs like the so-called Green Man. The Green Man is attributed to natural vegetation deities—but again, what is natural, what is nature—but so might the white man of the Doric or Roman column. Although it is more often attributed to some pale, western supremacy, forever being reinvented, reinforced, its terror lurid, tired, and everywhere. My warm hand flat on some cold column traced with ancient vegetal-mineral vines, my mind goes to Echard’s work again.

I think of her ceramic tile fresco at a Geneva maternity hospital (its alarming acronym: HUG). Its constellation of pharmacology also both ancient and nascent: medicinal plants and pills. For it, Echard created 2500 tiles, each featuring a vegetal bas-relief of therapeutic plants—rosehip, horsetail, mallow, moss, fern, ginseng, opium—constellated with pills and tablets. Cast like classical sculpture in clay, the tiles were enameled in copper, zinc, iron.12 All ancient healing elements and processes inherited from places like Messene, with its earth and fertility goddesses, sacred springs and plants, its sites of cult and commerce.

The trance of attention and connection, then loss, then, finally, memory. That is, the trance of the image.

The language of Echard’s Geneva fresco—its minimalist grid and pastel palette—seems pulled from both the binaries and nonbinaries of our health regimes. The natural and the synthetic, healing properties and dead herbariums, fossilized vegetation frozen into some rock-hard surface. The glazes, meanwhile, suggest the pale, flushed tones of an advertised maternity and childhood. Pale pinks, soft greenery, buttery yellows, each strobed with a cornucopia, a pharmacopeia, of properties, bodies, sexes, minerals, the ceramics representing a sense of safe, sterile enclosure via surface manufacture. What processes do this? Clay crystalized, silica melted and vitrified via alkalis and oxides. Exposure to heat, to alkaline earths and metal oxides. Surfaces and their transformations, lucid and burning.

In Messene, the sun burned. Springs flowed down through the site, its temples and treasuries. Such ancient sacred springs were once home to nymphs, oracles. The Romans replicated them, making fake grottos in their villas to symbolize leisure, sacred healing become luxury. Their nymphaea symbolized relaxation, control—though the future, as Cassandra would have told them, cannot be dictated.

In 2022, Echard made her own nymphaeum. A liquid tableau she called Escape More, it invokes both sacred springs and their recent corporate cousins, the minimalist water walls of business towers and shopping malls. Myriad forms of montage were given, from the flow of water to the flow of moving images to the flow of surface to the flow of one’s eyes across it all. Her water colored a faint yellow, like the mare urine used in hormone-replacement therapy; her images—advertorial, medical, gendered—overflowed with water, offering some neo-Impressionist-tinged fluid image. Water not meant to be felt but to be looked at, healing turned into an optical experience.

Montage, collage, palimpsest, surface, distance. Like the Romans, we believe we can improve nature’s processes by virtue of their virtuality, its representation in a new visual regime. Each image leads to another, placed in a flow of formal affinity, conceptual correspondence, material history, unfixed attention. The meaning found in the identification, assemblage, synthesis, corruption, contingency. The trance of attention and connection, then loss, then, finally, memory. That is, the trance of the image—and the ever-smaller returns of its endless recognitions and replacements. The trance of both transformation and stasis they give us, as we watch their advertorial tides go in and out: natural and synthetic, wet and dry, higher each time. Above us, the moon, strobe of its spotlight. As though this site was a set, artificially lit. It might be yet.

Twin Peaks, Splash Mountains

Mimosa writes:

I do feel a bit out of my context, a bit unrooted, which is why it’s interesting to work with photography because it is very free, very fluid… The city is a bit grim… The shows are a bit boring and it feels like everyone is exhausted. I love the shape of the city, the people are crazy and I love that. It scares me, though. I thought about David Lynch. I didn’t expect to be so affected by his death and realized that he was really important to me. The night he died the opening theme of Twin Peaks was spiraling around the East Village from the loudspeakers in a car and it was the most beautiful thing that has happened here so far.13

I remember our visit to her studio, all wood and windows, outside Paris. An artificial approximation of the country studio, manufactured for the creative, natural life. Its wide windows framing the grasses, flowers, and trees outside. Nature become an image of itself, one’s eye enacting the modernist flow of transparency and concurrence. In my memory, Echard’s wooden studio might have been something from Twin Peaks, its stage set of conspiratorial Americana Alpine kitsch and class and gender anxiety. I didn’t recall if we had discussed Lynch, though, or if I had told her that my father had worked with the filmmaker throughout my childhood. I imagine Echard in the East Village, listening as the Twin Peaks soundtrack floats across winter avenues. A kind of script tracing the New York streets. Surface streets, surface scenes, surface tension, all surfacing, again and again.

My own childhood seemed scored by Angelo Badalamenti’s beautiful, creeping compositions, Julee Cruise’s angelically weird voice. As a kid, I wore a Twin Peaks lighting department t-shirt to bed. One night my father had found me crying: I had picked up a script whose opening scene described a car accident in the desert, wild dogs eating the strewn and mutilated bodies against jumping flames. It was Wild at Heart. “This whole world is wild at heart and weird on top,” as Lulu says in the film, clutching her cigarette in some hotel bed. Weird on top: suggesting the importance of surface, its chromatic or corroded meanings. The heart below it wildly pumping. How to differentiate between the histories of images and the ones we produce anew, rates of acceptable exposure to various material?

Now I consider Lynch’s ludic surrealism versus Akerman’s social autofictions, though she played with gender and genre too, and in less patriarchal ways. In Paris, Echard and I watched a projection of Akerman’s first student film. We had never seen it before. A chubby, childlike Akerman—manic and charming—comes home to a tiny apartment, where she cooks, eats, and cleans, then blows herself up. It could not be more different from her first full work, News from Home, with its diaristic tracking shots of a dusky, color-soaked Manhattan. It is one of my favorite films, and Echard’s too.

Mimosa writes:

I thought about News from Home a lot… At some point I want to film the Times Square screens in extreme close-up (I already made a little video like this) and add a text, subtitles, something very intimate. Like a collage, like News from Home… I’ll send you a little extract…But I don’t know if it’s a good idea. I love the idea of working with just the movement of the advertisements, like synthetic tides.14

She gleans material culture and the surface of things—compelled by materials and their economies, chemicals and their properties, images and their histories, technologies and their translations, paranoia and its erotic reasonings.

The technologies of gender, of transportation and information—flows all—are embedded in the brick-colored surfaces of Akerman’s News from Home. Babette Mangolte’s poignant shots of the city subways, avenues, storefronts are recorded in a palette of deep blues, dark greens, rusty reds. As the camera moves smoothly across the city, mimicking the movement of cars and subways, so Akerman’s script moves, composed of letters by her mother. Perhaps it is this epistolary, maternal montage, with its deracinated displacements, that speaks to Echard, its ardent flow of both image and language—narrative and nonnarrative both. The infrastructures of communication and transportation synthesized by the film’s layered aesthetic structure, placed on the same filmic surface, then set in motion.

In News from Home, Akerman’s mother writes:

Dear Chantal, I sent you some summer clothes because it must be warm there. I hope I have the right address. I didn’t receive a letter this week. Last week three letters, and this week none. I hope you did receive my letters … I hope the shop will pick up a little. We have already started the winter collection. The son of one of my nieces is studying medicine. Why don’t you go see his parents in the Bronx? They know you want to make films.15

Under this anxious missive are images of some downtown corner, men and women hanging out on chairs in the violet dusk. A storefront of dark green glass, geometric and modernist, evokes a dime store Le Corbusier. A woman, sitting alone, arms crossed over her green dress, abuts a signal that reads in red: DON’T WALK. Akerman’s gleaning of her environment—her traumatized mother’s letters for her script, the city for her images—is an economy of means reflecting a larger world order striated by currents of connection and electricity, limits and thresholds, material poverties and virtuosic transformations. It is at the flow of such information that her lens is aimed, as at some surface.

Echard appears to work likewise. She gleans material culture and the surface of things—compelled by materials and their economies, chemicals and their properties, images and their histories, technologies and their translations, paranoia and its erotic reasonings—for the information of their transformations, that which slowly emerges, corroded or in bloom, in anxiety or in ecstasy, in eros or its advertisement. Her ethos appears to be the inevitability and intelligence of change, which comes—like water, like radiation, like love, like loss—in waves. We are penetrable beings made of electrical currents; everything moves through us, visually, physically, emotionally, chemically, fluidly. Our surface transformations the only information communicating the real change going on below, the images of history being eroded or exposed.

What records of information do Echard’s works offer? Chromatic, contaminated, communicative, full of biological resonance and synthetic matter, material histories and paranoia, eros and its slippery longing for capture, forms transforming and traveling, on loop. Like letters, communicating distances, longing and its languages, change or stasis. Surface flows as sacred springs as epistolary flows, as narrative and its technology both. From the flow of water to the flow of images, from the poor image to the rusting, oxidized surface, the synthetic pills to the healing plants, the libidinal to the sterilized, the charm to the antenna, the binary to the nonbinary, the protected or unprotected childhood to its most consumerist vision, material cultures to the prismatic orders of the immaterial.

Such is our news from home. Our most intimate, florid, and yet formal communication technologies. Information gleaned from the world, gorgeous and unstable and dying—for death is also a process, a transmutation of matter without conceivable end (we were all once stardust, remember). So. Information gathering, sharing; information overwhelm, its nascent ecologies. For sure: nature only exists if we consider ourselves outside of it.16 While the artificial only exists if we consider ourselves able to improve nature’s most intrinsic systems. Thus our attempts, also without end, to approximate this temporal and material flow, its images and seasons, matter organic and ambient, fake and fluid, because time, it seems, is so short. How to possess it. To slow it down through our record of its virtuosic changes. As with the seasons, glitching and glancing, by which we mark our most epistolary of exposures, our most formal (at least on the surface) of letters.

Mimosa writes to me:

I hope this finds you very well … sending swirls of snow from New York.17

I write to her:

It was lovely to meet in Paris, see the Akerman show together in December. Hope you and your partner are enjoying the city. Send news.18

Mimosa Echard: Sporal (Les presses du reel / Palaise de Tokyo, 2022) and Mimosa Echard: Mauve Dose (FCAC Geneva, 2018).

Email from the author to Mimosa Echard written on January 16, 2025.

Email from Mimosa Echard to the author written on January 29, 2025.

Jan Kłossowicz, Tadeusz Kantor. Teatr / Tadeusz Kantor. Theatre (Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1991). Quoted in “The Dead Class—Tadeusz Kantor,” in Culture.pl, at: https://culture.pl/en/work/the-dead-class-tadeusz-kantor

Walter Benjamin in a letter written in 1930 to Gershom Scholem. Quoted in Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (MIT Press, 1989), 36.

Walter Benjamin, The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin, 1910–1940, edited by Gershom Scholem and Theodor W. Adorno, trans. Manfred R. Jacobson and Evelyn M. Jacobson (University of Chicago Press, 1994), 359.

Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, “Translators’ Forward” in Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (The Belknap Press / Harvard University Press, 1999), x.

Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (MIT press, 1989), 36.

The title of Mimosa Echard’s exhibition at Galerie Chantal Crousel, October 15–November 16, 2024.

Hôtel des Acacias (1982). 16mm, color, 42 min. Directors: Yves Hanchar, Pierre Charles Rochette, François Vanderveken, Isabelle Willems, under the direction of Chantal Akerman and Michèle Blondeel. Production: INSAS—Institut National Supérieur des Arts du Spectacle et Techniques de Diffusion, Brussels.

Karen Barad, “Getting Real: Technoscientific Practices and the Materialization of Reality,” in Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Vol. 10 (Summer 1998), 87.

Christian Gonzenbach, “Parietal Pharmacology,” in Mimosa Echard: Mauve Dose (FCAC Geneva, 2018).

Email from Mimosa Echard to the author written on January 29, 2025.

Email from Mimosa Echard to the author written on January 29, 2025.

Letter taken from the script of Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1977).

Paraphrase of a line by Ailton Krenak, “Our Worlds Are at War,” in Amazonia: Anthology as Cosmology, eds. Kateryna Botanova and Quinn Latimer (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2021), 18.

Email from Mimosa Echard to the author written on January 29, 2025.

Email from the author to Mimosa Echard written on January 16, 2025.