Group Show

Artists: Paul Van Der Eerden and Elmar Trenkwalder.

La première exposition personnelle de Paul van der Eerden à la galerie a eu lieu en 1998. Elmar Trenkwalder a participé à l’exposition « e pericoloso sporgersi » en 1997 avant sa première exposition personnelle en 2003. C’est à ce moment que Eerden et Trenkwalder se sont connus et ils n’ont cessé depuis de correspondre, d’échanger parfois de retrouver leurs œuvres

dans des expositions collectives. À l’occasion des 35 ans de la galerie, j’ai voulu mettre en évidence ce dialogue. Bernard Jordan

Among Paul van der Eerden’s recent drawings, there is one – Untitled, as are

many of them – that is striking in its apparent simplicity. At first glance, the schematic outline in pencil, set against an evenly colored, light blue ground, might read as a hand gesturing as a “finger gun”, the index pointing and taking aim. But a closer look reveals that this hand can also be seen as a portrait in profile, the wide-open eye perched over the nose and looking out across the pictorial space. This graphic melding of the hand and the gaze, as in an optical illusion, functions as a commentary on the drawing process. Like partners in crime, the eye and the hand are about to launch into their uncharted trajectory across the paper’s surface.

Paul van der Eerden has stated time and again that he does not work from ideas. “[T]here is no real idea or plan behind it all. I just start drawing and then things evolve and go their own way until it stops, until the momentum is over.1

” But certain images, or themes, do reappear in his work: schematic body parts stacked or arranged to create geometric motifs, repeating faces with wide-open eyes and gaping mouths, butchered, splay-legged women, figures strangling one another, or engaging in some form of sexual activity. Cartoonish and brutal, awkward yet chilling, his drawings explore the full

range of human emotions and behaviors, leaving the viewer at once transfixed and disconcerted.

And yet, for all their violence, these finely crafted works on paper resonate with jewel-like perfection. There appears to be no line out of place, no color or contour that looks incongruous or accidental. Small in scale, the drawings beckon the eye closer, arresting the gaze with their full range of textures, from the glistening intensity of densely overlaid graphite to the veiled haziness of delicately nuanced tones in colored pencil.

In some drawings, the fragile Nepalese paper favored by the artist buckles and creases under the pressure of the pencil point or the felt tip marker, while still infusing the image with a luminous glow.

The inspiration of the day can arise from anywhere. Paul van der Eerden often

begins by tracing a line around the edge of his sheet of paper, circumscribing the space in which the hand will have free rein. A passage from a favored poem or literary work, or a visual recollection from his immense “inner image archive” may spark the imagination and push the hand in one direction or another. Text is present in many of his works, not written as such but drawn, the weight and color of the words becoming an inseparable part of the image, as in I am the eye…. The line from Shelley’s “Hymn of Apollo”, set against a black rectangular ground, suggests an atmosphere of foreboding

while anchoring the composition.

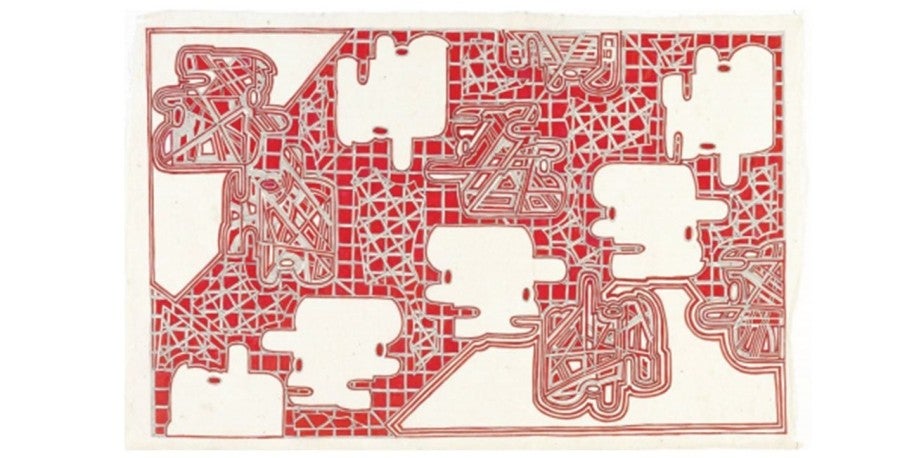

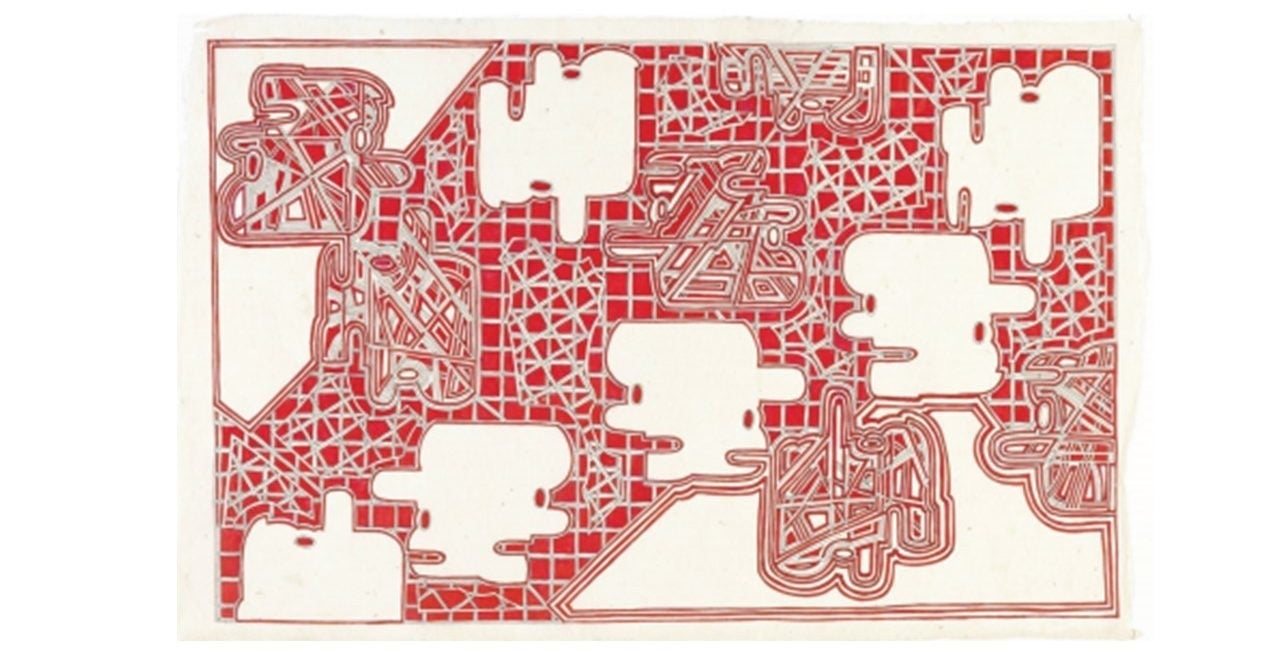

Other drawings abound with references to artworks and images as diverse as

medieval manuscript illuminations, Renaissance drawings, early 20th century modernist painting and comic book illustrations. The memory of “something medieval” led to the making of one of several larger Untitled works, drawn in ink, colored pencil and red felt tip pen. The repeating image of a dragon-like creature tumbles across the sheet of paper, its curved contours contrasting with the underlying geometric pattern and generating a sensation of perpetual kaleidoscopic movement. Throughout this series of drawings in red felt-tip pen, the viewer will again see schematized images of angry faces with wide-open eyes and gaping mouths, of splay-legged women and finger guns. But what ultimately interests the artist, beyond the emotional charge of these images, is the resolving of compositional problems that arise when making them, and the exploration of the infinite possibilities of drawing.

It’s perhaps this passion for process and craftsmanship that links Paul van der

Eerden’s work to the drawings and ceramic sculptures of Elmar Trenkwalder. Symmetrically composed, architectural in scale, Elmar Trenkwalder’s sculptures display a proliferation of phallic and vulvar forms, interlocked in a kind of ideal and ornamental uniting of the masculine and the feminine. Rigorously constructed yet profoundly intuitive, they entice the gaze into a disturbingly sensual, three-dimensional fantasy-scape.

The highly detailed and modeled surfaces retain the tactile presence of the artist’s hand.

Human figures, body parts and plant-like arabesques appear to be continuously morphing, as if infused with the energy of their making. In a small pencil drawing from 2002, WVZ 1124(2) , Elmar Trenkwalder may well be making a statement about his creative process. The drawing represents a hand, sensuously rendered in overlaid lines. The tips of the fingers have been transformed into glans, and embedded in the palm is a form suggesting both an eye and a vulva. It’s the hand that sees and feels, transforming sexually charged creative energy into visual and material form.

Beyond the omnipresence of sexual imagery in the work of both artists, a unique fusion of mastery and intuition characterizes their respective practices. Each artist produces works that are highly finished while leaving palpable traces of process. The kaleidoscopic spatial organization of Paul van der Eerden’s red felt-tip pen drawings echoes the symmetrical profusion of details in Elmar Trenkwalder’s sculptures. Like Paul van der Eerden, who begins his drawings by tracing a line around the edge of his sheet of paper, Elmar Trenkwalder often begins with a geometrically shaped base. Working upwards from a circular, square or rectangular slab of clay, interlocking figures and opulent details gradually emerge throughout the building process.

His recent, impressively tall sculptures appear to explicitly reveal this working

process. Deities or other strange figures are enthroned high upon columns or pedestals that are ornately adorned with abstract geometric patterns or human body parts. The sculptures are entirely glazed in white, inviting a play of light and shadow that accentuates the textures of the richly modeled surfaces. “Normally, says the artist, when I am building from the bottom upwards, I notice from a particular height onwards that the forms are coming together and that everything is just as it should be, just like an equation in mathematics. [Each part refers to every other part and yet is constantly changing], because while I’m working, I’m always making new decisions.(3)

” The columns, or the bases of these new sculptures, can be seen as the foundations of the creative process itself. Upon these foundations, raw material undergoes a metamorphosis to become the embodiment of a spiritual presence.

Diana Quinby

(1) Paul van der Eerden quoted in Patty Wageman, « Read while looking slowly » in cat. Sad Alchemy, Eelde, Museum De Buitenplaats, 2018, p. 65.

(2) Instead of titles, Elmar Trenkwalder identifies his works with an « inventory number », WVZ, or Werkverseichnis in German.

(3) Interview with Dorothee Mesmer, « Improvisation is part of it, as well as a lot of freedom », in Elmar Trenkwalder, Snoeck, 2012, p. 7.