Group Show Respawn

Artists: Stefan Bertalan, Nicolas Deshayes, Francesco Gennari, Karen Kilimnik, Gianni Politi.

« There are many ways to define God. But there is one among them that seems to be the most appropriate to actually explain the cycle of life and death. Assuming that in any religion God is first and foremost a piece of information, then the dizziness we feel when trying to look beyond this life, in the abyss of the unknown, tends to fade away. If God is a piece of information, so is death. The mystery surrounding it is part of that information regarding God, the same way as sleeping is part of life, and our hand is part of our body.

Death, according to Marcus Aurelius, is part of life – or, more precisely, is ‘part of nature’. And, we would add, we are allowed to know death only through this latter. In book IX of his Meditations, the Emperor-Philosopher writes: ‘As thou now waitest for the time when the child shall come out of thy wife’s womb, so be ready for the time when thy soul shall fall out of this envelope’. Then, in order to persuade us that it is actually possible to have a stoic attitude also when departing this life, Marcus Aurelius invites us to think about those who don’t share our same values, from whom by dying we will finally separate. Hence: ‘Come quick, O death, lest perchance I, too, should forget myself’.

From the idea of death seen as an end we move to that of death as a relief, or respawn. The rebirth of Super Mario Bros, archetype of the video game and epitome of the eternal return, doesn’t depend upon the programming (architecture of information as such) which “respawns” it indefinitely, but upon the player who imparts to Mario some of his skills, joining in for the the game. Apparently, if nobody plays ‘with’ him, Mario is only virtually alive – here it comes again the soul that ‘shall fall out of this envelope’, a typical detail of the many Last Judgement of the Renaissance age, starting from the one painted by Michelangelo for the Sistine Chapel. As a matter of fact Mario is dead anyway, also when he runs towards his objective, because contrary to the player he is a projection of, Mario neither has any notion of himself, nor he could ever have one.

This is the same cognitive effort that we make each time we try to overcome the ‘levels’ nature uses to challenge our survival instincts, isn’t it? It is within ourselves that we keep on looking in order to verify the world of information we are immerse in, starting really from that regarding God.

Stefan Bertalan (Răcăştie, 1930 – Timişoara, 2014) represented Romania at the 46th Venice Biennale in 1995 and he returned to the Biennale in 2013, the year before his death, as guest of the Central Pavilion. He spent his professional life looking for metaphors to depict the act of thinking and its structures. His field of research was the human being, within whom he tried to find a path in some ways similar to the one that Nicolas Deshayes is also looking for (Nancy, 1983). The discourse between interior and exterior, which has been characterising the work of the French artist since the beginning of his career, reveals a more and more humanistic nature, rather than a formal one. Colour, form and material are expressive tools at the service of dualisms – for the most part asymmetric ones – aimed above all at exploring the self.

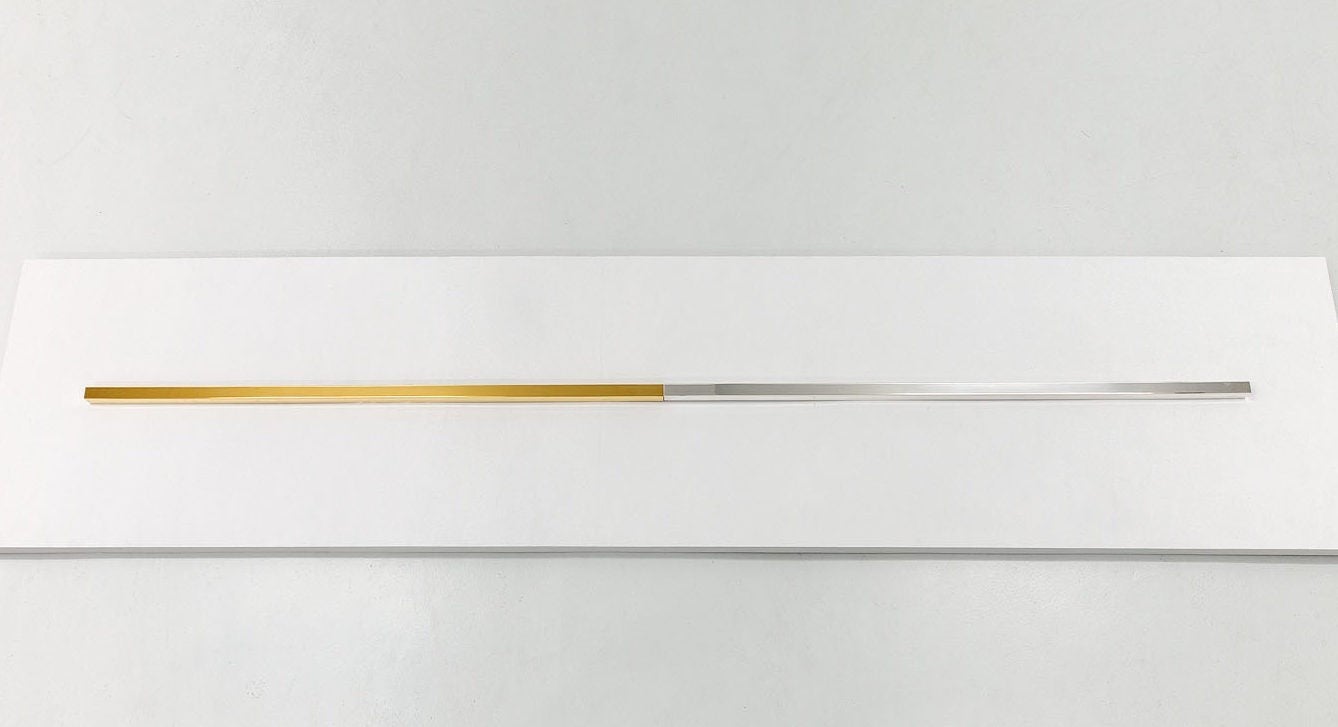

Karen Kilimnik (Philadelphia, 1955) remains within the realm of painting. Here she is represented by a symbolic canvas, gently suspended between night and day. What at at first glance could seem a waterfall of yellow colour, painted on the right side of the canvas, is in fact a paw floating on the undergrowth in a rather inquisitive way. Where am I? Where am I going? You can ask these questions only to yourself, and this is also the same field Francesco Gennari (Pesaro, 1973) coherently has been working on for a very long time. Sempre io/Still me, this is how the work on show is titled, is a formal challenge to the idea of the double, which Gennari interprets as two long metal rods, a gold and a silver one, placed on the floor one next to the other. There is an idea of infinity that runs in between. As Kilimnik’s animal stands on a soft ground, so the firm horizontality of the metal implies that of the support that hosts the rod.

The painting by Gianni Politi (Roma, 1986) hangs on the wall, and is clearly summed up in the title the artist gave it. The ego at issue is not absolute, but a personal and intimate one. What he is talking about concerns only who lived it. The piece of information thus becomes a diary. But the snake framing the painting reminds us that the present is the only thing that truly exists. »

Stefano Pirovano, 2019