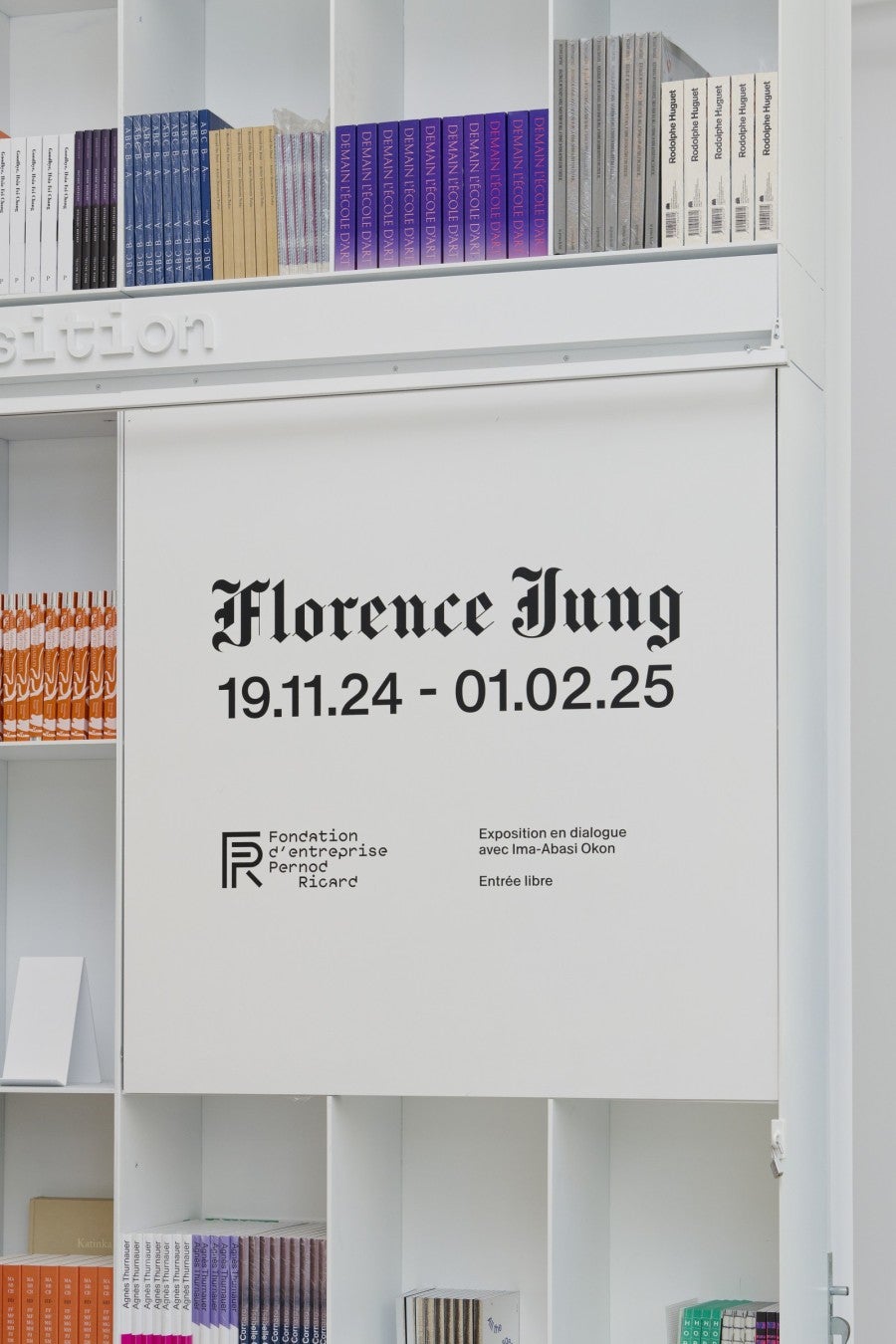

Solo Exhibition by Florence Jung

Florence Jung's solo show in dialogue with Ima-Abasi Okon

The exhibition unfolds ten scenarios, presented around the Fondation and its neighbourhood. Through these scripted situations, Florence Jung explores the lives of those whose paths we cross every day and the invisible ties that bind us.

Florence Jung’s work stands out through its conceptual richness, offering a profound examination of what remains invisible in our contemporary world saturated with images and information. Her approach is firmly rooted in reality, infiltrating daily life and encouraging viewers to question their environment.

My first encounter with her work dates back to 2013, when I saw one of her first artworks at the Salon de Montrouge. At that time, she had rented her exhibition space out to a tavern to fund a “Jung Prize”, destined to be equitably divvied up among all the artists of the Salon. There was absolutely nothing to contemplate on her stand, besides a waitress working away among her organic salads and— apart from the introductory text—nothing indicated either that it was, in fact, art. What might have been perceived as an attempt to thwart the conventions of the art world also served to ironically highlight the perversity of the competitive mechanisms that govern it.

Already, in this period, her approach had aroused my curiosity, as it focused not on visuals or objects, but on narrative, the ephemeral, and the intangible. Following the evolution of her artistic path, the specificity of her approach struck me as increasingly manifest. Florence Jung’s ability to create scenarios that slip into reality, blurring the boundaries between art, life, and the social sphere,

characterises the singularity of her practice. Her works are not confined to the traditional spatiotemporal limits of exhibitions; they extend beyond the immediate environment, integrating as much architecture as individuals.

This exhibition therefore marks an important moment both for Florence Jung and for the Fondation, as we are seeking to question and push back the limits of traditional exhibition formats, while reflecting on the role of institutions within the ecosystem of art.

Antonia Scintilla

Director of the Fondation Pernod Ricard

In plain view

Florence Jung is a poet that dovetails as an artist, one whose work makes the absent operational and relies on the strength of the blank. She does so via the creation of scenarios: constellations of elements and settings that, while seemingly secretive in nature, stand patent in their quiet orchestration of the commonplace and routine. In much the same way, Jung shifts attention away from herself, despite having let strangers into her apartment for one of her eponymous numbered works. Save for her name, Jung deliberately withholds details about her individual person. Instead, she underscores the societal structures in which we are all collectively (and often passively) embedded: not as an explicit goal of her practice, but as the inevitable result of pulling us away from the ceaseless din of our mediated distractions.

A singular outlook from inside the large glass windows of the Fondation Pernod Ricard are the platforms of the Gare de Paris-Saint-Lazare, the first station built in the Île-de-France in 1837. Flows of rush-hour commuters can be seen below heading towards their office spaces in the morning or home in the evening. However, these passing workers cannot easily look high up into the exhibition space. The vitreous container of the Fondation Pernod Ricard remains largely inscrutable from the outside while offering visitors a privileged vista of proximate urban elements from within—the bustle of the train station, street sights, neighboring rooftops—literally, the public domain.

Jung often uses the architectural space of her exhibitions as a viewing device, not so much for her own pieces but primarily of ourselves and our immediate surroundings. The Fondation Pernod Ricard is not an exception. As with her broader body of work, it might seem difficult to see precisely where Jung’s insertions within the city begin or end, even when these are in plain view. Yet it would be a mistake to assume this subtle nuance as anything but a precise call to focus: a clear framing that, like poetry, uses silence as emphasis and history as guide.

Ana María Gómez López