The Slow and the Magic. A Filmic World Between Waking and Dreaming

When I first started putting this text together in my head, I thought I had the perfect lens with which to contextualise the practice of the Paris-based Lebanese visual artist and filmmaker Ali Cherri. I thought I could use a slightly twisted popular culture reference to entice you whilst exploring some of the recurring and heavier themes in Cherri’s work through a more light-hearted perspective.

I was going to lean on the basic premise of the popular and, as far as I am aware, commercially successful Ben Stiller comedy franchise Night at the Museum (2026 – 2014). The films’ central idea is that things from the past, the supposedly dead and buried, can come back to life and haunt us at night. And in the case of said trilogy, which follows the classic Hollywood tropes, these encounters in the museum may initially seem scary but ultimately they can be funny and often heart-warming.

My rationale to take this approach as a metaphorical entryway into Cherri’s practice stemmed from watching his 2017 video Somniculus, a Latin word that translates to light sleep. In this nearly fifteen-minute work, scenes taken from black-and-white cinema where eyes are being removed (in some cases, seemingly gouged out) flash in front of our eyes as a preface. This brief assemblage is followed by the splicing of various footage filmed by Cherri, including of himself sleeping, interior shots of a number of world-renowned yet empty museums in Paris, such as Musée du Louvre and Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, with Cherri walking across the eerily lifeless gallery spaces. These shots are underscored by a consistent flow of an ambient-like electronic sound softly bubbling under the visual surface, waiting for a final exhale: the steady and clearly audible breathing of a fast asleep Cherri at the end. Inserted between is a static shot of Cherri performing a symbolic act of applying plaster across his own face/head, invoking mummification and the idea of turning oneself into an object, subsequently (and violently) slitting it open to reveal a single (computer-generated) blinking eye. The gentle simmering of soundscape quickly becomes an electrifying track during this scene, demarcating a tonal shift with the rest of the work.

'Somniculus' is a whispered reminder of how museums are also places that house the history of human brutalities.

Composed of a series of quietly assured and captivating gestures, the visual language in Somniculus is careful and meticulously choreographed. As if we are looking through a pair of eyes slowly and intimately scanning across ancient and othered objects on display. As if there is a hand gently caressing the masks, figurines, taxidermies and skeletons. The camera pans and moves at a glacial pace inside museums. The lens lingers on the eyes of those objects, some of which are wide open; others shut close, with a few hollow holes staring back at us. This repetition, the foci on those inanimate eyes, juxtaposed alongside scenes of sleep, weave together a visual tale of how the past, our ghosts, are resurrected repeatedly and lurking in our minds, whether our eyes are open or not. In deliberately situating this narrative within these prominent museums of a Western cultural capital, Cherri taps into the ongoing debate on the need to decolonise the (Western) museum. But rather than constructing a purely pointed and combative critique, Somniculus is a whispered reminder of how museums are also places that house the history of human brutalities. What Cherri has captured and translated through his eyes, and by extension, his lens, is a language of empathy, draped in an air of mystery and dreams. Enveloping the anguished outbursts and stillness of brutality is a tenderness towards the objects on display, and to a certain degree, the darkness that falls on us when we are confronted with the past. But more importantly, and on more than one occasion, reflections of the camera and the person behind it are clearly visible. This brings a sense of reality and honesty into play. It prevents the work from veering too far into the lyrical realm, striking a subtle balance between the imagined, the real life horror of the past and the awakening of such trauma in the present.

In hindsight, I was naïve, maybe too much so. The importance and weightiness of the subject matters in Cherri’s works, unresolved conflicts, unresolved pasts, ecological scars, means there is much more going on here than just a night at the museum.

1.

For the purpose of getting to know each other ‘better’, Cherri and I met at his studio in the outskirts of Paris one summer morning last year. He and his studio team were busy readying a number of sculptures and objects for his upcoming exhibitions in Bergamo, New York and Paris. His team was moving one of Cherri’s creature-like and often larger than life, yet surprisingly lightweight, sculptures in place for an impending shipment pickup.

Cherri works across a range of media from moving image to sculpture, installation and drawing. During my visit, aside from the opportunity of seeing the sculptures up close (and committing the sinful act of touching them), Cherri was generous enough to show me a clip of his then yet-to-be-finished new film The Watchman (2023), a centrepiece of his solo exhibition at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo.

The clip was essentially the opening sequence of the film. It consisted of a soldier standing guard in a watchtower-like space during a hot sunny day, alone and wordlessly. When we were watching it, we talked about the geopolitical tensions in Northern Cyprus, where The Watchman is set, and other similarly contested parts of the world such as the Korean Peninsula and the Taiwan Strait. We discussed how these decades-long tensions could easily slip into an everlasting sense of inaction, laying the foundation for an involuntary yet inevitable feeling of boredom to sink in. While we spoke, I also noticed how Cherri’s camera lingers on the somewhat bloodshot and seemingly unblinking eyes of the soldier. Without knowing the significance of those eyes and the soldier’s attempt to keep them open at the time, these shots planted this image of a sleep-deprived soldier in my head. As I began to draw mental parallels between this image of a tired soldier with scenes of a sleeping artist from Somniculus, our conversation naturally drifted towards the importance of ‘sleep’ and ‘dream’ in Cherri’s works. This was how the idea of tapping into Night of the Museum took shape. In addition, given how most of our exchange that morning centred around his films and videos, I made the suggestion that I would focus this text on his filmic practice.

Ali Cherri, The Watchman (extract), 2023. Video HD, color, sound, 26'. Courtesy the artist, Fondazione In Between Art Film and Galerie Imane Farès, Paris.

2.

Cherri’s moving image works are incredibly varied. Be it by genre, style or tone, attempts to group them under one simple classification is futile. This is not to say that they’re devoid of any common themes or subjects. On the contrary, they often share similar concerns regarding the consequential impacts of violence, trauma and senses of loss across space, time and cultures. Whether they are historic or contemporary, and whether large institutions such as a state have perpetrated them or results of nature’s way of realigning itself, the themes of Cherri’s works frequently address, imagine and symbolise how these impacts affect and dictate our way of life. Even when they are no longer visible or barely remembered, in Cherri’s filmic world, violence, traumas and loss from past and present are deeply ingrained matters. They intertwine with the habitual flow of our daily existence, only to re-emerge when we drift towards an idle state of mind. Their traces are buried and imbedded in our environments, in the earth we walk on, in the water we consume, in the sounds we hear, and in the inanimate objects we create and use, all of which are waiting to be unearthed, waiting to be seen and heard.

Just like how Somniculus evokes the idea that museum objects are carriers and reminders of our memories, the histories of (invisible) violence yawning to be resurrected in our dreams is a major thematic concern that recurs and permeates across other works by the artist. In his short The Digger (2015), a man watches over the ruins of a necropolis in the United Arab Emirates, walking across the desert to inspect the hollow holes, day in and day out. As the vista of the seemingly boundless landscape bleeds into the man’s quotidian solitude on screen, both visually and sonically, the vast emptiness of the natural world amplifies the nothingness. This nothingness is then heightened with footage of the displaced physical remnants of those losses put on view publicly in the clinical spaces of a museum, making the absence of loss and death in the now emptied graves materially felt.

...the land is traumatised, both figuratively and literally.

In Un Cercle autour du Soleil (2005) and The Disquiet (2013), Cherri has turned his gaze on his homeland, war-torn Lebanon. Taking on the role of a narrator via accompanying voiceovers, both of these intimate and fiercely personal visual meditations embrace a more documentary and video essay-like quality. And while both deal with and, to a certain extent, attempt to reconcile the country’s decades-long upheavals and devastations through its natural and built environments, the scars and traumas of war are keenly embodied and represented.

As we watch the clouds pass over a bright moon in the sky of Beirut in Un Cercle autour du Soleil, Cherri begins speaking:

‘During my early years, I loved darkness. Especially during the fighting, I used to close the curtains in my room, turned off the lights and get under the bedcovers. It was my way to create my survival environment, where nothing is necessary to me and everything could be invented…’

Night quickly becomes day, Beirut wakes for another day. Cherri’s voiceover flows across the images and the camera stays on the densely built capital city, tilting slowly at times. The scars of war are visible in some shots — a hollow abandoned shell of a building, holes and gunfight damage. Yet, what we see is also an ancient urban city standing still in the passage of time and histories, anticipating for the sun to set and the moon to rise again soon. Underscoring these visual and spoken layers here are the mundane sounds of the city: the honking of cars, blowing of wind and chirping of birds.

The sun also rises and life goes on in Cherri’s three-channel film projection Of Men and Gods and Mud (2022). Filmed at a traditional brickyard near the Merowe Dam on the river Nile in northern Sudan, the camera patiently follows and traces the routine of a group of brick makers. The dam is one of the largest infrastructure projects in Africa and has resulted in devastating environmental, political and social impacts in the region, including the displacement of thousands, unrest and forced acclimatisation. But in spite of this, the bricklayers still go to work in a muddy field, digging, hurling and moulding mud into bricks. They cook and they eat, they watch television and they play with their mobile phones. They rest, they sleep and they wake again for another day. The female voiceover, like the voice of god, walks us through myths about mud, of how we are all made of mud. There is a fable-like tone and quality.

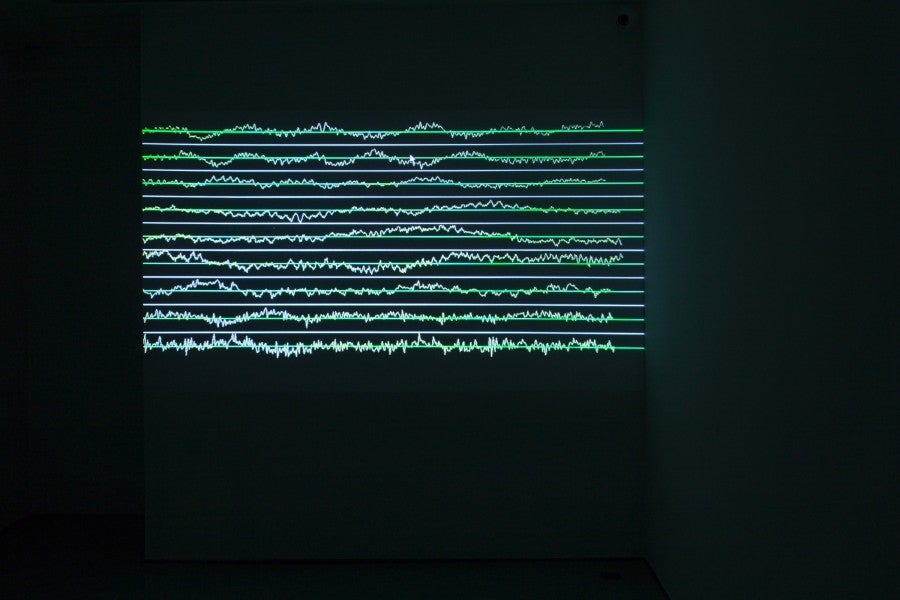

Whereas in The Disquiet, rather than capturing the traumas of Lebanon’s contemporary conflicts directly, Cherri opts for a metaphorical approach. Geologically speaking, the country stands atop of three active fault lines. These fractures have caused catastrophic earthquakes throughout history and continue to send shockwaves across the country on a daily basis. Using this as an anchor point, the main visual aspect of the work consists of POV shots of Cherri walking the land (of Lebanon). This first person perspective creates the feeling that we, the viewers, are there walking alongside Cherri as he scans the landscape. This, coupled with archive images of past catastrophes, the aftermath of earthquakes and filmed footage of seismometers and seismographs, weaves together a visual enquiry into the psychology of living on a land of traumas. In The Disquiet, the land is traumatised, both figuratively and literally. So, while an earthquake can permanently alter the landscape, other scars could be just as deep-seeded, waiting knowingly for the next catastrophe to strike.

Cherri revisits this notion of living in a (psychological) limbo in his most recent short The Watchman. Set in the United Nations patrolled buffer zone between the Republic of Cyprus and the mostly unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, the film depicts the internalised fear of a soldier stationed there. The soldier struggles to stay awake when standing guard. Nothing seems to happen, except being present (trapped) in this perpetual place of possible violence with the vastness of its landscape stretching endlessly ahead. Yet, in a surrealist fashion, the history of this troubled region is manifested through a group of impossibly tall zombie-like soldiers lurking in the hills, marching towards the watchtower when darkness falls upon the land. Although we see these creatures on the screen, I cannot say for sure if they are only supposed to be a figment of the soldier’s imagination, existing solely in the dreams of the protagonist. Nevertheless, this surrealist turn brings forth a more ambiguous dimension in which an inhabited fear is allowed to formally materialise.

3.

Cherri’s moving image works often embrace the fantastical, whether he is operating in the documentary or fictional realm.

However, despite these thematic common grounds, as a filmmaker, Cherri remains fluid in his visual and stylistic approach. Though some of his films are more narratively concrete than others, he persistently shifts between different modes, crossing back and forth between the documentary, the fictional, the investigative, the allegorical and the experimental, and at times, blurring, fusing and straddling boundaries in one single filmic expression. Yet another potential frame of reference that unites them, is their artistic affiliation to the the traditions of ‘slow cinema’1. Whereas most of the films associated with this movement are typically known, even celebrated, for their use of long takes, which doesn’t always or necessarily apply to Cherri, his works do otherwise attain and exhibit some of slow cinema’s other characteristics and aesthetic tools. Take Cherri’s employment of a minimalist and observational manner in capturing and constructing visuals and narratives. His never intrusive camera serves as a pair of keen eyes, quietly witnessing and retaining what it sees. Rigorously composed and framed, the camera only ever moves so slowly as not to disturb its subjects. These highly intentional gestures offer the freedom for scenes to unfold unhurriedly, and sometimes, wordlessly across the screens, opening up the possibility of a contemplative space for us to reflect upon.

This slowness is no doubt mentally demanding or even challenging to many contemporary audiences, but it has become even more pronounced in the artist’s more recent works. Perhaps it is a sign of Cherri’s growing confidence as a visual storyteller as he refines a very specific kind of aesthetics. And I suspect this development is, at least partially, due to how the language of slow cinema has the natural tendency to occupy the lyrical zone, arguably more so than most of the other cinematic traditions. On the other hand, the influence of ‘landscape theory’ on Cherri seems probable, even palpable. Also known as ‘fukeiron’ and devised by the film professional Masao Matsuda in 1969, landscape theory is a radical Japanese cinematic movement that explored and utilised images of the common everyday landscape as a site to expose invisible social and political structures. This strategy is certainly akin to landscape’s critical role in visualising the no longer visible histories and violence in Cherri’s works. But more importantly, like the surrealist conclusion in The Watchman, Cherri’s moving image works often embrace the fantastical, whether he is operating in the documentary or fictional realm. This penchant propels Cherri’s films into the terrain of magic realism. For instance, his first feature length work, The Dam (2022), is teeming with supernatural elements.

For this film, Cherri returned to shoot in the area of the Merowe Dam in Sudan. Based upon similar thematic and spiritual veins, The Dam can be viewed as an expanded companion to Of Men and Gods and Mud. Here, it centres on the life of Maher, an individual brick maker. The film opens with wide shots of the desert landscape and a panning shot of the dam. As the camera pans across the screen, we see a small group of makeshift hut-like structures in the shadow of the enormous dam. This is when and where we first encounter our protagonist. Maher is sitting on a rock, replacing the batteries of a battered radio. Music and news soon take over the soundscape as Maher and his colleagues get ready for the day. Once again, Cherri’s restrained gaze resurfaces to capture the mundane activities, and news of ongoing protests elsewhere in the country slowly gives way to the sounds of water boiling in a kettle and a river rushing through the metal tubes of the dam. Settling into the rhythms of the day and working alongside others, Maher digs, hurls and moulds mud under the heat of a shining sun. But each evening, as the night begins to descend, Maher is seen building a mysterious structure with mud and tree branches in the desert alone. Gradually, the structure grows in size and takes on an otherworldly presence, consuming the life of Maher and all that surrounds it.

It is a world that conveys senses of compassion and tenderness towards its subjects and the environments they inhabit.

Magic realism is a literary device most associated with novels written by authors such as Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Salman Rushdie. However, its quality of inserting ‘magic’ elements into realistic narratives has also been utilised in cinema. Magic realism can be an artistic proposition that represents and tackles histories or socio-political events too difficult or implausible to comprehend in real life, a quality that deeply resonates with Cherri’s films and videos.

The Dam, for example, has been compared to the magic realist films of Thai artist and filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul by some film critics2. Weerasethakul’s films such as Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) and Cemetery of Splendor (2015) allude to the historical and recent political traumas of Thailand through fantasies, myths and folklores. But I would argue that the film Still Life (2006) by the Chinese director Jia Zhangke, one of the leading figures of slow cinema working today, is an equally warranted candidate for comparison. Deploying a three-fold interconnected narrative structure, Still Life takes place in a small town on the banks of the Yangtze River during the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, an enormous and controversial infrastructural project not so dissimilar to the Merowe Dam. While the core narrative is an emotive human story, the film is a visual meditation and a humanist expression on (urban) displacement and the loss of a certain way of life, as the town goes through the process of withering away due to the building of the dam. It also exhibits a touch of marked magical (surrealist) fantasy such as a building rocketing to the sky like a spaceship and the surprising appearance of a UFO, bringing about a sense of the absurd, an escape of a fated reality. And even though the magic in Jia’s film is decidedly fleeting and less pointed, critical or imperative than those developed and realised by Cherri in The Dam or The Watchman or Somniculus, it is worth mentioning since such gestures, no matter how small or big, can be a way to visually speak of the invisible and the rather forgotten.

By now, it would be easy for me to say that the filmic world of Ali Cherri is an interpreted tableau of traumas, a world populated with monsters, creatures, ghosts and (super)natural forces when darkness falls. But what Cherri has managed to imagine and construct is not a cinema of despair or doom. With his lingering camera, the attentive gaze, and the gentle and considered pacing of images and sounds, Cherri has instead created a slow and magical world. It is a world that conveys senses of compassion and tenderness towards its subjects and the environments they inhabit. Of course, there are moments of darkness. How can there not be when we confront the scars and traumas of war, violence and displacement? Yet, those moments of darkness are precisely there for the mundane to take root, for the flow of life and time to take place, and for the scars and traumas to become visible again.