1.

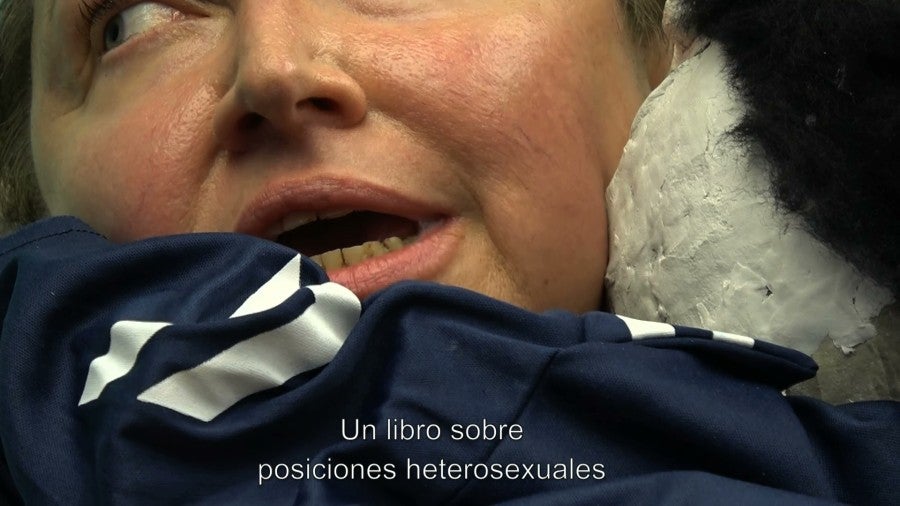

Liv Schulman had hinted at the possible commission of this text to me in the last months of 2023. On that occasion I contributed a piece of writing for a group exhibition at her gallery in Buenos Aires. In that text, I tried not to explain the works but to find some device to talk about them from the writing itself without referring to them specifically. Returning to it now, I find a paragraph inspired by one of her videos. A puppet tells a group of police officers that the idea of identity is a hindrance. That what is important is the flow of exchanges. The matter of the essence of thinking is located at the limits of the body. It is a folded surface. The puppet gives an example: the best model to imagine it is your own sex. Your sex is a surface, it does not matter if it is concave or convex. What matters is that it is designed to be in contact.

Months later, the invitation was formalised with an email from the Pernod Ricard Foundation. They offered a fee of 1500 euros and to pay the costs of a trip that would enable a meeting between the artist and the writer. I immediately accepted. I was interested in Liv Schulman’s work, I felt I had something to learn from it. I couldn’t put into words exactly what it is. I had a virtual meeting with someone from the foundation. Because of her schedule, the artist suggested that the meeting take place in Buenos Aires as she was planning to shoot a video in the city. The foundation agreed for the meeting to happen in Buenos Aires and I finally accepted too, although it discouraged me a little. The fee was less of a motivation than the trip. In order to receive the fee, I would have to arrange the transfer from abroad to Argentina, which involves getting tangled up in several procedures: filling out a form with the invoice to submit it to the bank. The Argentinian tax system does not allow invoicing people who are not registered in the country. Besides, the commission is variable. If the procedure is delayed for any reason, which is always likely, the amount transferred is converted into local currency under the official exchange rate. In Argentina there is a big difference between the official and the illegal exchange rate. The transaction is not only time-consuming with endless procedures, but also ruinous: the 1500 euros fee would end up being 750. How could I explain this financial labyrinth to the foundation, with my limited English or French, without sounding like a criminal? How not to appear overly concerned about the fee rather than the project?

Identity is a hindrance, what matters are the interconnections.

I accepted the commission. I really do feel I have something to learn from Liv Schulman’s work. I began to imagine other ways to solve the problem. One possibility was to ask the foundation to buy me a plane ticket with the money allocated for my fee. I started to devise a plan. A few months ago, I had an affair with Johanna in Buenos Aires. She is a trans woman, like me, and German. She works in political economy and has worked in the German Parliament. Johanna is thinking of doing her doctoral thesis on the subject of the Argentinian debt. She was in Buenos Aires for a few weeks to apply for her doctorate. That is when we met. I remember very clearly the softness with which she spoke, the calm cadence of the rhythm of her voice and the gestures that made the strands of straight blonde hair curl towards her cheekbones, creating a delicate transparency over her green eyes. Her comprehension and expression in Spanish are perfect. I marvelled at the way she understood my way of speaking, so distinctive of the people from Buenos Aires, that confusion between speaking and thinking out loud. But it’s not a simple decision for me to travel to Berlin, where she lives. After getting her attention, seducing her and starting to see each other, I felt strange. I can’t put this feeling into words. In my mind, Johanna appeared as a reflection of myself. The similarities are obvious, but there was something more that I could not quite make out. I think the way she listened to me made me suspect that in her, precisely in her silences, nestled something similar to me but different. In that game of mirrors, my strangeness seemed to reflect back a certain disapproval of my own body, which emerged like the shadow of a question that I thought I had overcome. It is about gestures that I unravel in my reflections, reading her movements when we had sex. Travelling specifically to see her in her city would make me feel vulnerable, helpless on unfamiliar ground.

Embroiled in financial and administrative calculations, in the translations and errors of my emotional exchanges, in considering the risk of my decisions, I return to the words of that puppet in Liv Schulman’s video: identity is a hindrance, what matters are the interconnections. Desire circulates in that liminal space that brings bodies together and separates them.

2.

Transactions, negotiations and losses are recurring methods in Liv Schulman’s work. In her video The Disappearance (2013), she spends the prize money she received by exchanging it over and over again on the triple border between Puerto Iguazú in Argentina, Ciudad del Este, Paraguay and Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil. The action is literally buying money with money, and in that movement, everything is lost. Consumption becomes consummation, in the sense of what is extinguished. The exchange leads to ruin. The anxiety of constant calculation turns into a loss of control. With each ruinous purchase, she feels that her surroundings become unreal, and the only possible link begins to be a paranoid conversation with herself. From the perspective of the French sociologist Marcel Mauss, every exchange functions as a reciprocal gift, a potlatch, a network of solidarities woven from this giving and receiving. But here, this logic leads to the disappearance of the exchangeable, to the sacrifice not only of profit but also of the body that negotiates. The economy becomes an economy of the desire for loss. Following a surrealist reading, we could say that this flow becomes an unconscious and sexualised desire that tends towards loss. This occurs precisely in the scenario of three geopolitical borders. In this unconscious dimension, the border that is crossed is that of the body itself, which is extinguished in each exchange.

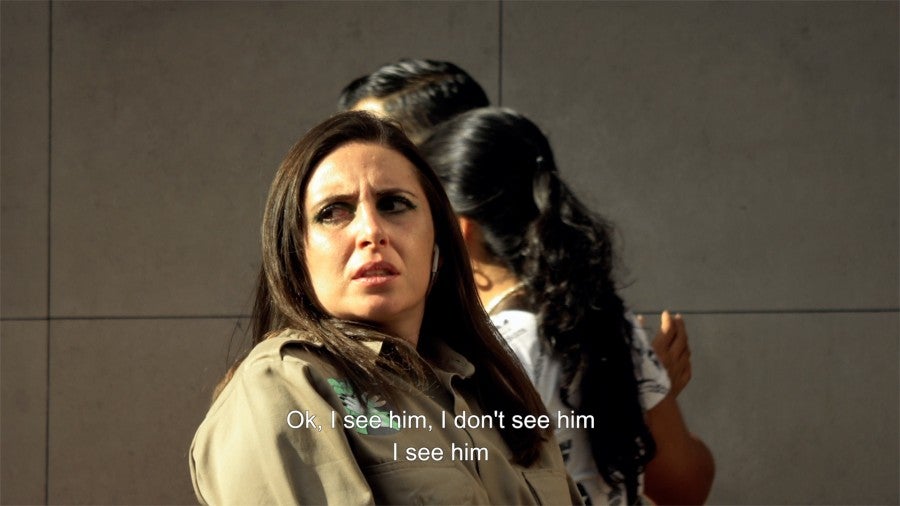

The border and negotiation reappear in the video A Somatic Play (2019). The scene includes two customs agents wandering around Mexico City watching a myriad of legal and informal, conscious and unconscious trades, on a division of territories that is not clearly perceived. Walking through popular markets, hair salons, street food stalls and different corners, they control the passers-by. Mental health crises, peasant uprisings, Louis Vuitton wallets, fetishism, “privatised fantasies”, anxiolytics, debt bonds, jeans trafficking, undeclared narcissistic tendencies: the agents list these things consecutively. They also discuss a group of women who sell and buy Avon products from each other until they generate a rotating energy of buying and selling. The products gradually increased in price and then shrank in size until they disappeared. The dividends plummeted; this circuit consumed itself. The agents regulate the libidinal economy, export desire and illegally import anxiolytics, flooding the black market. The border that is always transgressed is that of the body and its fantasies. Again: identity is a hindrance; it is the interconnections that matter.

3.

Liv Schulman, A Circle That Rolled Away, 6K video, 35' min, 2024. Courtesy of the artist

I meet Liv Schulman in Microcentro, the financial district of Buenos Aires. The streets are filled with the conversations of those walking, and a series of voices seems to create a pulse that marks the pace of everything: change, change, change. It is the sound of illegal dollar traders. The reason we met there was that we were planning to take the same urban tour seen in her latest video, A Circle That Rolled Away (2024). The project started from an observation: people in this city express themselves in the streets. They narrate what they are going through. They talk about their emotional states but they also seek to get the other person to settle into a particular mood. They give and seek something in return. This reflection by Liv Schulman is possible because of distance, this space that has opened up since she moved to Paris. The characters in her film are many and they are scattered among the regular people who walk along the street. They are so many that sometimes it is unclear who belongs to this fictional universe and who doesn’t. Altogether, they form a kind of choreography and soundtrack of a continuous dialogue that shapes a thought spoken out loud, which seems to belong to the city itself.

As we talk, Liv Schulman stops in front of various buildings. Her gaze seems to reach them. As I watch her, a few gestures spring to mind: I run my fingertips along the lintels, the cornices, the lines of windows and pillars I see from a distance. It is like touching them, it feels good; the distant is somehow within reach. By caressing them in this way, shapes are formed in the air, geometric drawings that evaporate in seconds. To touch them in this way is a caress, a slight touch in which you feel them close. Speaking is also a caress between the lips. No matter what is being said. The pleasure that Liv Schulman feels, that I feel, that the people who talk while passing by feel, is comforting.

We continue walking down Calle Florida and reach Avenida Corrientes. We see the corporate logos crowning the skyscrapers, each a promise of security, welfare, fun, joy, surprise, novelty. The city speaks, it always speaks. We can let it lead us to the excitement it promises us. In A Circle That Rolled Away, two office workers talk and one tells the other that she has the ability to feel through other people, that they can feel through her and she can feel them feeling her. The office worker says that everyone has an ability and a need. That woman is one among hundreds of thousands who could be in any of these windows Liv Schulman and I are looking at from street level. The office worker could be like a space of confluence of all this collective conversation we are witnessing. A meeting point for all the exchanges. The vertex where everything that is given, promised and demanded in the city comes together.

Do you know the German restaurant? You’re going to love it, says Liv Schulman. We leave our tour, enter the hall of one of these glass buildings and go up to the twenty-first floor. Through the windows we can see the skyline of towers over a green and ochre mass of trees that precedes the continuous brown plane that forms the Rio de la Plata. Liv Schulman mentions that she used to come here to write the script for the video. The towers reflect each other to the point of confusion. We lose the concrete measure of their limits. From this height the city looks like a series of circuits, conduits, interconnected modules. A soft and porous structure like a fabric, a weave of reflections. I look at the horizon and think: this is the material infrastructure of all our exchanges. The space that brings our bodies together and separates them.

4.

A character wanders through a commercial area of Buenos Aires, passing through street markets, talking to anyone from street vendors to dogs. He starts crying over a poster on a wall. This is how one episode of the series Control a TV Show (2010–17) begins. As he roams, he develops a theory postulating the advent of a new collectivism: the Middle Ages still exist today, only no one knows it, dear friend. In his theory, individuality dissolves into a permanent being together. CIA agents are the new relational artists, only no one knows it. Taxi drivers are existentialists, only no one knows it. Migrant bodies belong to the state, only no one knows it. Neoliberalism would paradoxically be the emergence of a collective body made up of exchanges. As he continues to speak, he starts caressing everything within reach. Lying on the ground, he runs his fingers through the cracks in the tiles. He also touches the hair of a street vendor while he continues this monologue. Another character caresses a fashion magazine in an old factory. She says that neoliberalism is the new shamanic resistance, only no one knows it. She explains it in these terms: at some point someone invented a system of simultaneous agency and exchange that would later take the form of an exacerbated conversation. As they wander through the city, the figure of a ghostly collective body emerges, present only in the murmurs of various paranoid theories about the secret. The body is an illusion, my dear friend, only no one knows it.

5.

I see Liv Schulman and think of the collective bodies that appear in her works. To me they look like organisms gathered by soft bonds that keep them in contact.

I see her standing still looking at a frieze composed of groups of swirling bodies, overlapping with each other. The frieze is arranged in different frames, like a comic strip. With great attention Liv Schulman pauses on the surface, lingering as if she could touch it. We are at the Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires, observing the twelve panels of the conquest of Mexico, painted by Miguel Gonzalez in the seventeenth century. I am struck by this human group that unfolds as if it were the same entity at different times. A group in which it is difficult to distinguish the central characters. They all form a large interconnected body that shapes this frieze of history. I see Liv Schulman and think of the collective bodies that appear in her works. To me they look like organisms gathered by soft bonds that keep them in contact. These bonds are filaments that place them in juxtaposed, always uncomfortable, positions. The characters look tired, a bit out of it, dizzy. They expose a kind of collective conversation in which they seem to be mere interpreters.

A group of visitors listen to the explanation of one of the museum guides about the artwork. I can imagine her repeating it several times a day. I imagine the way she chooses the words, how she selects her gestures and movements in the room. We sit down and watch her. Liv Schulman explains to me that the gestures of her actors always pass through her own body first. Later comes the stage where they make proposals, which they negotiate until that finally crystallises on the screen or in the exhibition space. The work starts with research, different resources that Liv brings into contact with the performers and their bodies. One needs to start somewhere, she says. She uses a writer’s method: interviews, conversations, archives, documents, theories, techniques, everything can be assembled. The important thing is that these materials serve as a foundation to then let oneself go. To start from something in order to get lost. A source she always has at hand is the art world itself – its references, emblematic works, logics of circulation, its statements and the things that are left unsaid or suspected.

We continue to wander through the museum corridors. Tired, we end up sitting on a bench in front of a painting by Jorge De la Vega: Intimidad de un tímido [Intimacy of a Shy Person] from 1963. The canvas shows a series of intertwined shapes that create strange and dislocated forms. We are struck by the use of folded and wrinkled fabrics that contort the surface of the painting. On one side there is a character folded in on himself, the folds of the fabric are tighter. From there another figure emerges connected by a kind of umbilical cord. The latter has a big jaw and is painted in strident colours. A little distracted, we start talking about random things. I surprise myself confessing to her that before transitioning, I found it very difficult to seduce people. I was shy to the point of being paralysed. My theory is that the gender role I was expected to play always made me feel inadequate, stuck in a place that prevented me from taking the initiative. When I was able to fully embrace myself as a trans woman, the act of flirting, of having lovers, awakened a new awareness in me. In the game of seduction, the surface of an elastic space unfolds, enveloping us all. The logic of sexual exchange brings us together in a soft space of folds and juxtapositions. Liv Schulman listens to me and responds that, for her, it’s also like that – exchange is always self-knowledge. Even if the results of that inquiry hurt us. Maybe you couldn’t play that game before because you hadn’t set up your own stage. She repeats: it is very important to set up your scenario. Once you put yourself in that place, your body finds its gestures, its words, and can arrange things in a way that feels more possible, more effective. What is important is not the identity of these bodies, but their location, their tactical place.

6.

Six women are gathered around a table. It is not clear whether they are at a work meeting or are part of a Narcotics Anonymous meeting. They recount their lives: travels, studies, significant dates, exiles, friendships, lovers, partners, exhibitions, artistic trends, aesthetic theories, manifestos and interpretations. They do so in different languages. Sometimes they talk peacefully, other times they argue, get angry, lose control, explode, enter into episodes of paroxysm or revelation. In the work Le Goubernement (2019) these six women represent an archival investigation into artists who have often been marginalised in art history. These are women artists, lesbians, queer, trans or those who rejected the gender identity assigned to them. They were all active in Paris between 1920 and 1970. The research for this work began with Liv Schulman’s investigation into the Marc Vaux Archive, which belongs to the Kandinsky Library. There she found over 130,000 plates documenting the artistic life in Montparnasse, a district of Paris, during those five decades. These images recover destroyed, lost or forgotten works; studios that had never been recorded before; and exhibitions that were previously unknown.

Historical documents merge with fiction, chronicles from different past eras mix with contemporary references.

We could say that a sort of anti-museum is staged in this work; a place where whispers, cries, confessions or arguments represent voices that have not been preserved from the decay of time. Liv Schulman’s research encompasses almost sixty artists but did not assign each of the performers fixed identities to represent. Marie Vassilieff, Claude Cahun or Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, for example, can assume the bodies of different actresses or the same one simultaneously. Their voices unfold or overlap. It is not so much about personifying them as if developing a character, but about giving body to this frieze of history made up of all these intertwined figures. Thus, a kind of paranoid revisionism unfolds, where theories are set against each other and biographies are reinterpreted a thousand times through speech. Historical documents merge with fiction, chronicles from different past eras mix with contemporary references. It’s as if the actresses embody a body of work, they wear some of the images from the archive printed on their clothes, they show photographs that they take out of folders or that are printed directly on their skin. They are people, they are talking objects, documents arguing with one another, an open set to multiple interpretations where the identity of each biography blurs to the point of becoming indistinguishable. Once again: identity is a hindrance, what matters are the interconnections, the new interpretations.

7.

The brown horizon line, the Rio de la Plata, is as wide as the sea. Between the water and us, a shore of stones and mud. Looking closer, the stones are pieces of cobblestone, fragments of brick walls, whimsical shapes of concrete and river stones. This beach is a still decaying old rubbish dump. An intense smell cuts our breath away, coming from hundreds of gutted fish between the stones and the soil. This city grows over its remains, thus gaining land to the river. In the distance are the buildings we saw on our first walk. The mirrored towers reflect each other, some of the company logos visible from afar. On this land, real estate development had built a new city of corporate buildings and rental flats. The voraciousness of the real-estate world was imposed on a modest piece of land where now plumes, stunted shrubs and other weeds grow. For thousands of kilometres, the river carried the seeds that germinate here. On this green strip of land, we could see the river and the city from afar. This unusual terrain, a border space, allowed us to contemplate more clearly the sediments of different eras, evident like the rings of a cut tree trunk.

Taking advantage of this landscape, I suggested to Liv Schulman that we talk about economics. I reminded her that her works often mention Avon products and that several of her characters caress Tupperware containers while they talk. Both products are emblems of what is known as multi-level marketing, a direct sales marketing system. It is a world of part-time saleswomen who use the spare time from their domestic tasks or primary jobs to earn some extra money that would allow them to make ends meet. To join, they need to get into debt, pay for franchises, recruit other people from their close circles. This is how capitalism slowly infiltrates spaces where it had not been present in that way before. It becomes parasitic – on ties, spaces and situations that previously corresponded to the realm of family life, friendships or a neighbourhood. It made me think about these substrates that form the edge of Buenos Aires. The waste of the city, what it expels, was constituting another territory that later proved fertile for the city’s own expansion. Liv Schulman’s mother was an Avon Lady. She also made her daughter attend numerous casting calls for television, film and advertising. Liv Schulman was once cast in a chewing gum commercial. Years later she asked her mother what she did with the money from the commercial. ‘I fed you for a month with it’, she replied. We found the image amusing – that Liv Schulman ate thanks to the advertisement for something you chew but don't swallow. Between jokes we discovered a common generational experience: as girls we experienced how the structures that divided work and family life, men’s and women’s tasks, friendships and work were altered, retracted and other exchanges grew out of them. These new links expanded like a soft and flexible web, occupying every possible loophole. Like this old landfill we were talking about, once an abject and separate space, later established as a suitable place for the growth of these mirrored towers that blur into one another. Neither she nor I can escape this landscape that surrounds us; we live, think and feel within its perimeters.

While talking and looking at the brown horizon of the river, the image of a strange and disproportionate body came back to me, looming over the whole landscape. Its figure appeared to me, feeding on its own excrement, as if folded over the path from its mouth to its anus. Feeding on its waste, it grows bigger and bigger until it covers everything. This body no longer needs to walk or pick things up with its hands. It loses its shape; its only movement is growth. In its development it fractures the divisions that organise our life: sleep and wakefulness, work and leisure, food and waste, viscera and skin. Its sex is only a surface, it no longer matters whether it is concave or convex, it is designed to be in contact.

8.

How do economy and sex, word and jouissance, the illegal and fantasy, the city and the body, the viscera and the skin link together?

We walk back to the city, talking about anything and everything. Once again, I tell her about my romantic ups and downs. I tell her I was thinking of travelling to Berlin to visit Johanna, the German trans girl with that soft way of speaking and her blonde hair, transparent over the green of her eyes. I talk about my conflicts with my own body and the possibility of seeing a reflection of myself in her. I also mention my idea of exchanging my earnings for a ticket to Berlin. Liv Schulman suggests that she could ask the foundation to transfer the money to her account in Europe and buy the ticket. I thank her for the offer, I feel like we are exchanging. My dedication to writing this text as best as I could would be rewarded by this gesture. Are we becoming friends? Together we established other solidarities that extend beyond the limit of institutional assignments.

Once I drop Liv Schulman off at her bus stop, I walk on and ponder what this experience had meant to me. I wonder what I had gained from it all. I have a feeling that some experiences bind us together. The figure of someone who was forced to give herself to a nomadic, sometimes lonely path often appears in my mind. In her escape, she left behind the things that were closest to her, things as diverse as learning to recognise the hidden intentions of the most familiar phrases, the way meals are enjoyed or the entertainments we were taught in childhood. Leaving all this behind, she began to make other connections, other translations. What once seemed natural, or self-evident, began to lose meaning. As she wandered, she rehearsed a general theory of the world: How do economy and sex, word and jouissance, the illegal and fantasy, the city and the body, the viscera and the skin link together? And speaking aloud, immersed in a thousand digressions on the subject, now exhausted, she suddenly noticed the touch of her lips, her tongue, her palate, and her teeth as she pronounced these phrases. She became aware of the rhythm of her own breathing. She looked at the environment around her and seemed to caress it with her eyes. She settled in a certain pleasure of the here and now; she found a shelter in the vibration of her words. This perception made her question her boundaries, she went beyond what she could have imagined. She was struck by the impression that she can sense what others feel, becoming a fold within a fabric where her body is just another form in a landscape so vast that its limits fade into the horizon.