Doing Women-Blanket-Basket: Persisting in pleasure despite it all

Doing-woman is “to want to be a woman.” You must be affected by the other and distribute the small and the humble throughout your body. To be a woman is not as fundamental a position as its opposite, to be a man, so instead of thinking of it as a thing to discard, each person must travel toward their inherent feminine plurality, the overflowing feminine existence within. One also needs a biological awareness of being a woman and discern with one’s energy the woman within one’s connections with other objects. I want to be reborn as a woman of another identity every day. In my text, I am a girl today and reborn an old woman tomorrow. I was a blade of grass today and tomorrow will be born a hunting bear. I want to be reborn as a color, a pattern, an image, or a small sign. I am not one woman but a multitude of women, not a woman here but here and there, a woman who makes the here a here-less there. To want to become a woman inevitably leads to empathy on a level of pure energy.1

Doing is an active verb. Here, by saying “doing,” following the Korean poet Kim Hyesoon, I attribute a headless quality to this verb and recognize movement in being. In doing, there is no subject-head that judges the depth, good and evil, and fixates orders. Instead, there is a body-mind – mind is not just in the brain – spirit of “women” that do, generate (life), and keep going in tandem with others. Others here might well appear in blankets or baskets or more. So, we shall explore “doing blanket” or “doing basket” as in doing women in the words of Kim Hyesoon, through doing-art by Seulgi Lee who was born and grew up in South Korea and has been based in France since the age of nineteen. Please let us note that if there is anything identified as Korean here, that it is simply for the doing of it – making it plural – as for doing the other, being “Ixcatlán,” “basket” or “blanket” as Seulgi Lee being or rather doing women must be “affected by the other and distribute the small and the humble” through her body. If this “leads to empathy on a level of pure energy,” I would also let us recognize it as the pleasure of doing, despite of all that tends to oppress it or make it impossible, which the artist evokes again and again.

1.

...each elemental shape slowly becomes a kaleidoscopic whole. Such an experience is not the end, however.

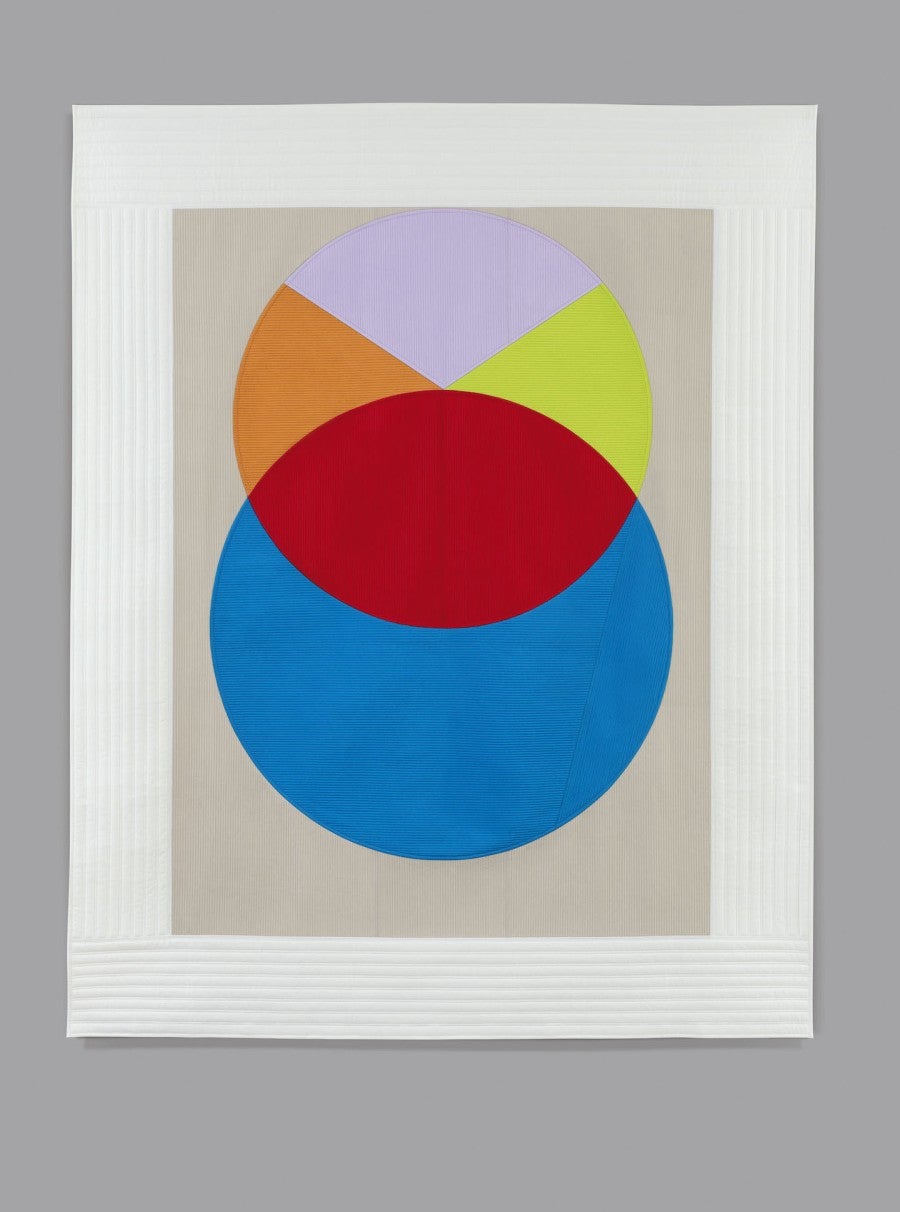

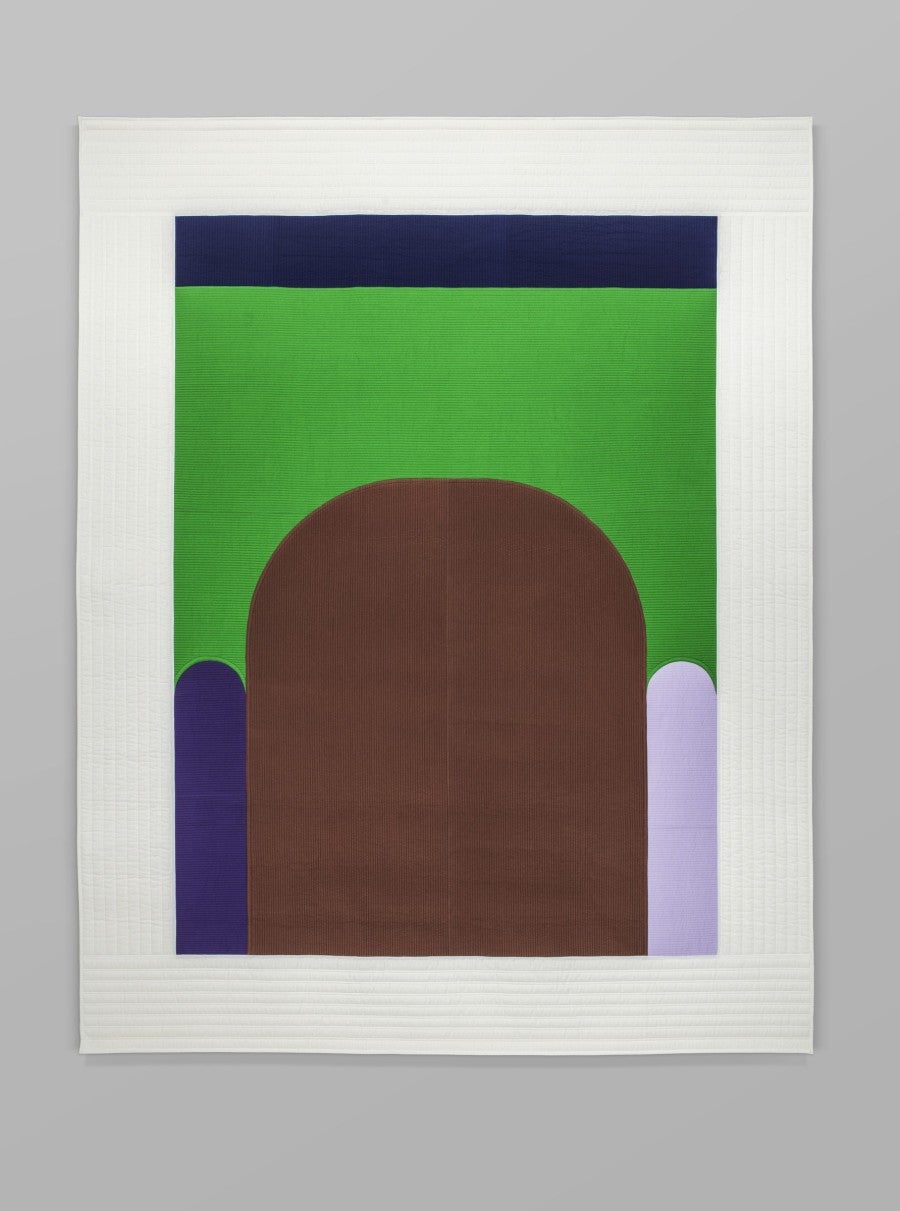

A series of blankets with their particular textures and geometric shapes in bright colors caught my eye. It was in the context of a large-scale international exhibition. They were not hung but laid over low, light-gray pedestals. Besides different shapes and compositions of colors for each blanket, they had in common recognizable, yet subtle patterns made through the threads of fine sewing. Any household in Korea might have had at least one such type of blanket called a Nubi, if not its mechanically produced version, until a couple of decades ago. Sewing was done across the whole blanket over parallel horizontal or vertical lines. It reinforces otherwise fragile silk or artificial silk fabric while still holding its specific gentle and light quality. The shiny surface of the fabric mostly combines different pieces of fabrics of bright colors and gives the room light and character. Sure my family had a couple of them. Ours were mostly for summer use. During a typically very hot and humid Korean summer night, you habitually kick off your blanket and expose your body to the breeze coming from an all-night-running electric fan. Hit by sudden cold air at dawn, you find your stomach aching in the morning, but it is too hot to hold onto your blanket. Yet, having the Nubi ibul (blanket in Korean) prevents you from that likely summer illness. Touching you, it keeps you cool and protected at the same time. It covers you with an elegant breathing space between itself and your body. This whole sensation I have with my own Nubi ibul was evoked when I saw such Nubi ibul in art form. So, I went to look at them closer, as I was curious, too, of what was going on with all these bright colored different geometric shapes. These blankets are part of Seulgi Lee’s ongoing project called Blanket Project U (since 2015).

One can indulge in the varied geometric shapes, each of which is composed of different intense colors. Being geometric and framed by the typically rectangular shape of any blanket, it is the rounded and curved that dominate the scene. They dance, rise up and settle down, expand and shrink by leaving nothing in a shadow – physically impossible but they seem to be possible, all bright, and each elemental shape slowly becomes a kaleidoscopic whole. Such an experience is not the end, however. Drawn to the title of each blanket piece that is either a proverb or customized vernacular expression, you can engage in actively translating the seen visual into the verbal or vice versa. Earlier works of the series mostly held a four-character idiom shared in the Sinosphere and commonly in use in Korea. Over the cover of a blanket, for instance, Dok Su Gong Bang 독수공방 is “written” in a large purple field where a partial oval shape of pastel pink shyly appears on one edge of the blanket. Dok Su Gong Bang literally means keeping an empty room by oneself, usually applied to describe a woman waiting a long time for her husband who has been away. One may wonder, is the purple field the expression of a deep mind’s solitude? Is the emergent or disappearing shape of light pink about the heart that longs for presence in the absence? Certainly there’s no displeasure in doing Dok Su Gong Bang as expressed by the blanket, which may well defy the patriarchal culture underlying the expression. The expression Saak-I No-rat-ta 싹이 노랗다 whose literal meaning is “the sprout is yellow” is spoken mostly by elders to children or youth as a way of scolding their reckless or rude behavior. Rather than cursing anyone to remain hopeless – as a yellow sprout refers to those that cannot grow well – it is a casual expression that makes the situation of nuisance into an everyday farce and therefore lets it pass. For this, a long, oval shape of bright yellow, indicating a yellow sprout – which in reality might be somewhat withered – is positioned against the magenta background. The magenta field may seem to cry out the sensation of scolding or being scolded – unleashing and bearable. If any power is implied in this scene of uttering or hearing Saak-I No-rat-ta, it’s that power that the blanket chuckles away. As for another way of scolding from anyone to anyone, the proverb So Il-ko Wae-yang-kan Go-tchin-da소 잃고 외양간 고친다 refers to the situation that your action is too late to improve at all. So is a cow, Wae-yang-kan is a stable, Go-tchin-da means “repair” in Korean. So seems to be expressed through the brown colored background – an easy association. Requiring a more subtle verbal-visual interpretation, that the cow is already lost, may be clearly expressed in two different shades of purple. We also could take notice that the small margins of these two purple shapes are filled with turquoise. May they tell of a rather belated, hence useless effort to fix the stable? However, it does not matter so much (as doing blanket would suggest)?

Not all the expressions in the titles of the blanket-works are concerned with a troubling situation. However, as gathered here, they together tell how life lessons are taught to and from one another, describing a situation that anyone can imagine. Above all, they function to bring together the common experience of such situations: staying with trouble. Visualized in geometric shapes of colors and materialized into a Nubi blanket, this function seems to even elevate you into a joyful horizon, while dealing with any problematic structure of the expressed situations. They are cheering empathizers, vibrant equalizers – neither simulators nor unifiers – of whatever experience of life, be it hardship, mistake, or underlying inequality and injustice, one is having. They might bring a person into brightness, into vital positivity, and into an eternal movement of acceptance only to re-imagine and create another situation, another identity. Imagine the sensation of being protected by the blanket, resting, and even dreaming under it. This is the moment when one could begin to do a blanket, or rather begin doing blankets!

2.

...she shifted otherwise disappearing or forgotten heritage into the spotlight.

In “doing blankets,” one cannot help but address that both Nubi blankets and proverbs or vernacular idioms in Korea share a similar socio-cultural status. They have been pushed into the margins, less and less used over the goods and language of smooth and fast digital circulation. The crafted blanket is replaced with a mass produced, uniformly stylized one. In place of proverbs or idioms, there are memes. You are learning these expressions less by studying with a textbook than by living a culture, and this culture is what is formed through generations. Nubi stitching is a craftwork that has its own specialization. It is now protected by the South Korean cultural policy as intangible heritage. The disappearance of diversity in our Anthropocene world is not only true in the natural and biological worlds but in language and culture. It is uncertain how many of these, like Nubi blankets and the culture and/or language-specific verbal expressions, can survive. This concern may well allow us to value Seulgi Lee’s Blanket project U from a perspective of cultural preservation, as well. Through her collaboration with a Nubi craftsman in Tongyong, a port city in the South Korean peninsula, she shifted otherwise disappearing or forgotten heritage into the spotlight. Curiously, however, the artist asserts that the purpose of her work is not to preserve a lost language or lost tradition. Then what is it? A recent interview she gave to a Korean newspaper leaves a clue2.

The reporter asked the artist where her idea of combining Nubi blankets with Korean proverbs stemmed from. Seulgi Lee shared an anecdote about a blanket she received as a gift when she first came to Paris in the early 1990s but that afterwards she herself could no longer find to purchase anywhere: “Thus I wanted to make it as an artwork.” And she adds, “I saw the blanket being a common everyday object as sort of a frontier between reality and dream, I’ve imagined that it would be fun to have stories on the pattern of the blanket.” While she continues to elaborate on the meaning of working with the blankets and proverbs, the notion of “fun” remains stuck in my mind, as it is mentioned again and again throughout the interview. In responding to the question of when she became determined to become an artist, she expresses that her thinking centers around how to keep practicing art with pleasure, rather than treating it as an occupation, even though she has wanted to be an artist since childhood. Both of her parents are artists themselves so it’s no surprise that they were a big influence on her, but she was also determined not to take an art professorship to earn a living as her parents did, to avoid doing art as an occupation. As if to confirm this, Seulgi answers at the end of the interview when the reporter asks her to share any habit that is foundational for her practice, “I try to see work not as work but as fun, as plaisir,” she adds in French.

I have come to dwell on the nature of this “plaisir” as she says, as opposed to work, occupation, or job. The overt positivity of the blankets of her Blanket Project U, as aligned with this artistic attitude, has also made me wonder about it, especially in relation to the saddening fact that the Nubi craft is now only a specialized, barely surviving traditional skill. And a vernacular culture of language is also affected by globalization. Aren’t we living in a broken world of increasing destruction, violence and inequality? Having said that, provided that making every blanket in the Blanket project U necessitated the close collaboration with a craft person, I wonder, is this pleasure a shared, and shareable one? In fact, Seulgi Lee’s “work” often involves collaborative process or interactive moments. Amongst her collaborative works, the blanket pieces in particular, which are an outcome of the collaboration between Seulgi Lee and the artisan Sungyeon Cho in Tongyong, have, in the artist’s own words, been loved the most. They have been collected by public museums and private collectors, so widely and for such a long time, as to become a sort of currency for the artist. If this is so, is any benefit, be it financial or symbolic, shared between the artist and her collaborating artisan? Seulgi Lee had no hesitation or difficulty in answering that. She has an ongoing discussion with her by now long-term artisan-collaborator on the fee she offers to him. The collaborator expresses what he considers a fair payment, which they agree upon, premised on the clear distinction as he sees that she and he each deal with different markets. Having her own currency allows Seulgi Lee to “invest” her income into her next project, which gives her a degree of (artistic) autonomy. Still, one can argue the contemporary socio-technological and political condition for pleasure requires some examination with regards to the forms it takes, how it is generated, where the pleasure comes from. Pleasure can easily be a form of escapism, to distract oneself from facing reality, serious engagement and production of meaning. Differently to indulgent pleasure, there is also a pleasure of disinterest, which in the Kantian view was regarded as the defining property of aesthetic judgment and the capacity of imagination, as the aesthetic experience is free either from moral or rational thinking. Yet the matter of art is no longer confined to disinterested pleasure and aesthetics as we have seen the complex mechanism of context and institution, and interpretation and action that have transformed the notion of art for the last century. Seulgi Lee’s art practice should not be an exception to it.

3.

Seulgi Lee’s pleasure-seeking, or her art giving pleasure, is far from passive surrender or cowardly escapism.

A conclusion one could make effortlessly is that Seulgi Lee’s pleasure-seeking, or her art giving pleasure, is far from passive surrender or cowardly escapism. If we are being attentive to the (art) “works” by Seulgi Lee, however, we can say it is rather an intense yet non-obtrusive refusal of any looming or imposed cloud, shadow, darkness, or stillness, especially when they come to block, capture, deaden, and enclose a state of being. It is a kind of pleasure consciously or even disciplinarily sought after and claimed through the act of making, articulating, and doing it together. What it is making is the basis of life. What it is articulating is the common and elemental knowledge of life, which is surviving despite it all. It is not necessarily a denial of it when she asserts that her work is not about preserving lost language or tradition. There seems to be the larger cause that is to form, or even constitute a way of living as to be found in and to adapt to these intergenerational, old, “surviving” forms of sustaining life and living together, that are simple, haptic, grounded with care and relational. Not an exuberant, singular artistic expression but a step away from everydayness, towards a sustainable state of it as a verb, a kind of verb that keeps up a radical openness. Therefore the blankets as conceived by Seulgi Lee with no order or authority, move us to the “state” of doing baskets, too, as we will shortly see. A practice against all those that come and hamper our doing them, which actively maintains ways of being empathetic, non-judgmental, even forgiving, and generative of joy3.

4.

….

I climb underneath the ash

my country is beyond the horizon

all plains all river

the edges can be crossed with care

you might say that language is

harsh

but it is an ancient beauty

a life that rolls and sings

and we’re singing we’re singingI wake up to a woman

wading through all birds

heart shaped leaves

with perfect breasts that hang

long and heavy

scars along her chesther basket is safety

everything worth holding in two hands

has a perfect basket to respond

first you must begin

with the grasses

first you must tend the blades

the sweet small shoots

first you must make healthy the soil

care for this place

tend with fire

carry the seeds

first you must make the land right

first you must love your motherwhat you care for will care for you

when you are ready

you will understand

how to make a basket4

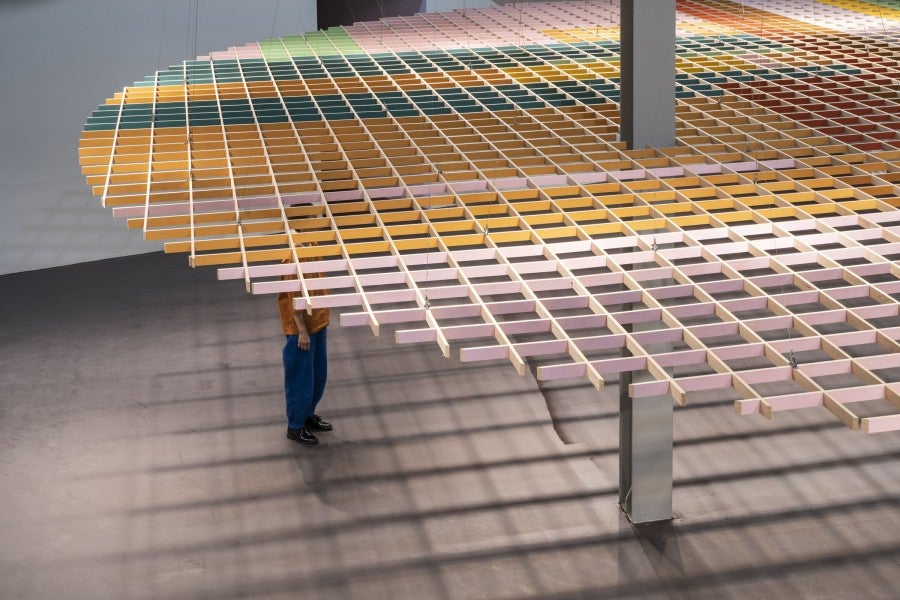

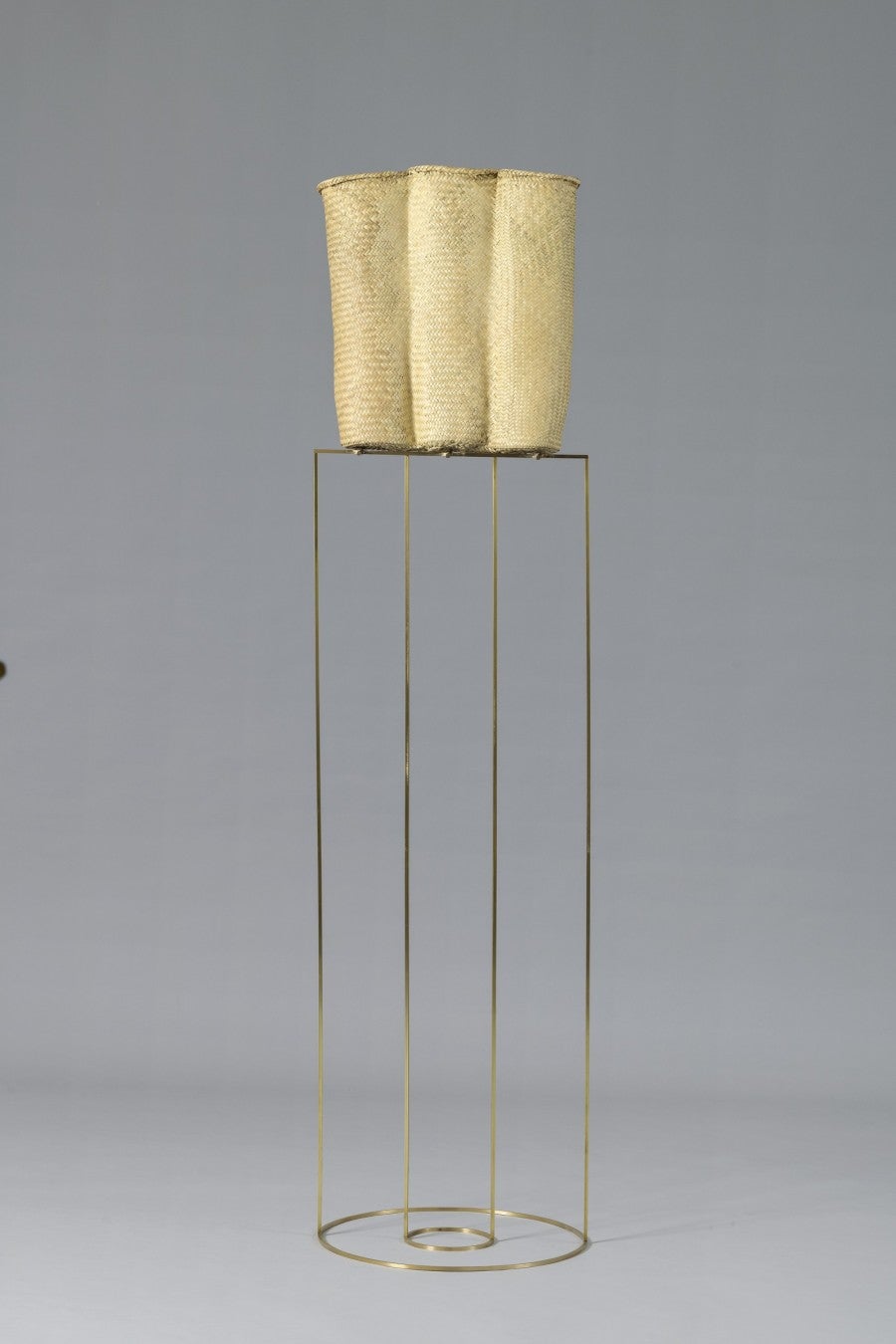

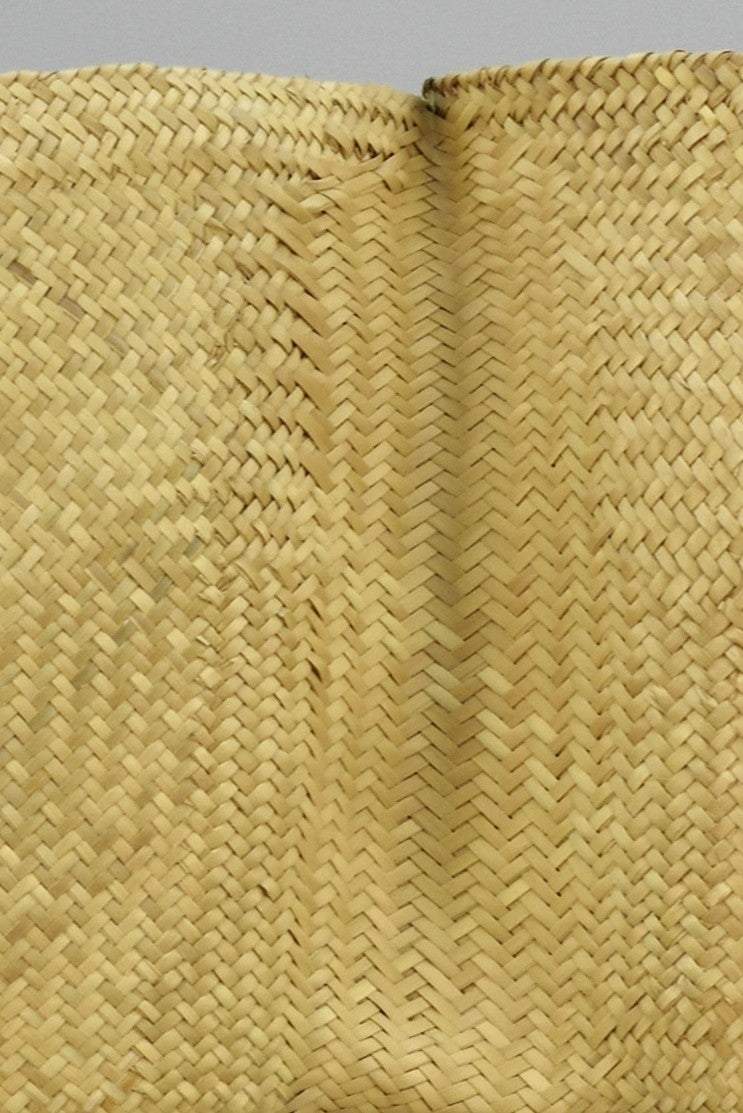

“Doing basket” is something else and yet akin to “doing blanket.” Here I refer to Seulgi Lee’s Basket Project W (2017). It might well be said that this project has evolved from Blanket Project U not only chronologically but in the conditioning and conceptual approach. Taken up a few years later, it was with the income generated through the Blanket Project U that the artist could self-fund a trip to Mexico to meet and possibly work together with artisans. This time, it’s an old form of basket and the tradition of basket-weaving with local palm leaves in order to have its forms adapted. A basket, like a Nubi blanket, is another useful, old, everyday object specific to a culture, whose forms and skills to make have existed for generations and have been replaced by machine production with plastic materials. The similarities between the blanket project and the basket series include also the element of language. Whereas each blanket expresses a (Korean) proverb or vernacular expression, each basket expresses a descriptive word(s) of the surrounding environment and customs in the language of the village of the basket weavers, which however is rarely spoken as it has been replaced by Spanish, the language of colonial power. In fact, the majority of about 200 villagers are not able to speak Ixcateco, the indigenous language of the small village of Santa María Ixcatlán in the present-day state of Oaxaca. Such language is now spoken by the baskets whose shapes are not as usual as adapted from the common forms through the collaboration between Seulgi Lee and the Zapotec weavers. They are not big or lengthy words so one might learn to practice: duchdi is rain, hwagutchaku is sunset, ʔu²sa²chã³ is coyote, sa² la² kwa²shu1ngu² la² shhũ¹ itzie ske², means young girl with neat hair, sa kwa²ne² sa² ra² thwã¹, to eat an egg. We come to read them, or even speak them through the baskets whose shapes are now altered and thus enliven to speak. The baskets are now made longer or wider than usual and are joined together in three. The smaller and shorter ones make a set of twins. Some other baskets either in single or as duo or trio have one or two smaller basket(s) attached on the sides. It looks as if they have ears or a nose. Actually, they are the bodies and faces; thin golden metallic structures hold these baskets when the artist exhibits them and form the bodies and in turn allow the faces to appear.

If the blankets of Project U were creating kaleidoscopic movements, these do a gymnastic dance. It’s from there that the sense of joy or pleasure arises. The “everyday” scene of the Ixcatlán baskets as they are shapeshifting. And it’s from here that the moment of “doing baskets” comes. They are no longer by-gone utilities or useless craft to preserve but the living one, asking you to move along, doing it, doing them, to doing duchdi, doing hwagutchaku, doing ʔu²sa²chã³, doing sa² la² kwa²shu1ngu² la² shhũ¹ itzie ske², until sa kwa²ne² sa² ra² thwã¹.

...is what we could call decolonization and indigenization taking place?

The risk of collaboration in the making of the basket-works might have been higher than in the Blanket Project U since Zapotec culture, or even Mexican culture, is not the artist’s own. Never mind Ixcatec, Seulgi Lee does not even speak Spanish. Although she is not from Tongyoung, the Nubi culture, until recently, was broadly shared in Korea. The artist’s foreignness to Tongyoung is not in the framework of the settler colonialism versus the indigenous sovereignty relationship either, even though the depreciation of the craft of stitching Nubi and the Nubi blankets might be considered something of indirect colonial influence. Here the artist may have come as other Spanish, European, or urban settlers, and used “cheap” weaving labor to make an art project of high (financial) value. Therefore it is important to note that the artist limited the making of this series of works to the time of her stay during which she, as well as a couple of her friends who went there with her, joined the process of making; the collaboration was with a cooperative of women weavers which requested the appropriate fee; the artist met all agreements with cash payment. Besides, the works indeed serve to honor the work undertaken by the women and remember and recognize the value of the disappearing language, in an attempt to preserve it. Or rather beyond honoring, we had come to learn “doing basket” – that is with or becoming weaving hands, weaving subjects in a manner of being empathetic, moving, and generative of and with pleasure, despite it all.

how to make a basket (2021), a poem by Jazz Money, a poet and artist of Wiradjuri heritage, tells us more about the meaning of “doing basket” and how, despite the catastrophic, man-made wildfire that happened in her own ancestral land in Australia. Imaikalani Kalahele, a Kanaka Maoli /native Hawaiian musician, poet, artist, and activist, makes sculptures with basket weaving. He speaks of his ongoing basketry sculpture series with the following: “We are not just making baskets to hold something but to resemble something. We are making them to look like something else, to represent something else, and to hold something.”5 Although not of the Ixcatec’s own initiative and the works are not authored as such, Basket Project W seems to echo what these indigenous artists speak of baskets. In doing women, doing blanket, and doing basket, is what we could call decolonization and indigenization taking place?

5.

I would like to repeat the question but ask differently whether doing women, doing blanket, and doing basket contribute to decolonization and indigenization, and how. The reason for this shift lies in that the artworks by Seulgi Lee seem to resist any big words, conceptual, and academic notions, even though the works led me to arrive at those. Or perhaps it’s because the artist is in the position that saying them is not a simple matter. This position may well come from having been born and growing up in South Korea, a country that was once colonized and is still in a long process of decolonization, while it is now also the colonizer even if it is still at war, a complex legacy of colonialism. Indigenization is not a familiar word either in a common sense or in critical discourse that the artist may belong to, as the word came with the western colonization. Korea was the colony of Japan, the “empire” which ironically took an anti-colonial stance against the west in its colonial venture into Asia. Still, the artist would not agree with any of this identification. Nor is it what we may get from doing blankets or baskets.

Seulgi Lee acknowledges that living in France as a woman who was born and grew up in Korea until she came to Paris in her late teens made her question who she really was. People had kept asking her where she came from. Tired of the same questions over and again, one day she even replied, “I come from Africa.” It might be a problematic response as it could other “the Other” again. But what if it is only to be and do “the other”, among many others, and that’s what she or her work would keep doing? In that regard, it becomes even more relevant that the artist invited the figure of mischievous monstrosity in her earlier works. The work PLUIE (RAIN) (2005) is an example. It rains from the hair of a woman whose face we are not able to see, which makes a fountain. What does the fountain imply? Water falling from the head into the fountain promises a cyclical and continuous movement that does not define a beginning or ending, isn’t this what woman – doing women – represent? In the artist words,

I’m interested in shaping this state of in-between, transformation of the heap (amas) of hairs like vegetative mass, into a liquid state. I’m trying to keep this state in suspense, the water flows as much as it can, it is a fountain functioning in a continuous loop. The sound of the water blurs our perception of time in a repetitive movement, leading us in an endless time. Or even restful, introducing a grotesque dimension on a head without voice. […]

The name PLUIE is coming from this visible movement from top to bottom, and it is a fountain emphasizing the transfigured link. I take the rain for a fountain, I like to imagine things being upside down, such as the relationship with others...6

IDO (2009), which sounds like the French word hideux, meaning hideous or ugly, introduced a hairy monster on the façade of a public bus and let it run across the city of Bordeaux. It “transfigures” the everyday vehicle as well as everyday roads with humor, surprise, and pleasure. What is called ugly is only to cut across what is already designed, constructed and fixed which are enabled by power like a nation state or colonial regime that conveniently makes use of identification and categorization, even to determine what is human and what is not. If indigenization is a long process that needs somewhat painful unlearning of our possessive, predatory, extractive, and productivist habits, Seulgi Lee’s work gives support for us to undertake that process by unsettling the status quo and whatever becomes objectified, and even almost lost for that reason, animating them, bringing movements to them, or rather doing them. In doing, not ceasing at a being, we must be “affected by the other and distribute the small and the humble” through our bodies. This would lead us to “empathy on a level of pure energy,” in which we find pleasure despite all the challenges, and a fountain for an endless loop, that is the continuity of such empathetic movements. By the way, do you know, it’s said by the beloved and respected elder and scholar of indigenous epistemology Manulani Aluli Meyer, that the synonym for indigeneity is continuity7? As I have learned, the notion of continuity is found in intergenerational stories, stories of ancestors, stories of lands that feed us people who in turn take care of those lands, and languages and cultures living them. It is not about identity or racial distinction but the daily practice of loving: that is continuity. So now we may know where our doing with pleasure goes.