1.

If you click on the heading “sculpture” on Jean-Claude Ruggirello’s website, you’ll come across almost quaint, pedestal pieces like Chiens (2008) made from kitschy readymade porcelain dog statues enwreathed in a tangle of wire, as well as monumental sculptures like Toi Nuage Passe Devant (2006) comprised of two kayaks bent like origami on tall stands.

Categorized with sculpture you’ll also find King Kong (1998) an installation of two automated projectors that swivel on stands and send rectangles of projected light back and forth across a curved wall. Principe Actif (2004) described as an electro-vibration projection system, appears as a projection of two interlocking geometric shapes that create a split screen shape on the wall.

The day I sat down with Ruggirello in his studio for a generous visit, I was able to see some of his smaller-scale sculptures, and maquettes for sculptures, as well as works on paper, but we spent most of our time talking and looking at documentation and at some of his video work on his computer. I asked about two of his early works that intrigued me when I consulted the copious files he had previously emailed me, His Master’s Voice (1984) and Deux Jours (1984), which he also categorizes as sculpture on the website. The documentation of the performance His Master’s Voice shows several distinct scenes, reminiscent of images in a photo-novella, a genre Ruggirello has experimented with. In one image, we see Ruggirello from the waist, holding a walkie-talkie to his mouth, and in another we see a young man wearing swimming goggles, crouching on a red taped mark on the brown carpet. He holds a walkie-talkie to his ear with one hand and a hatchet in the other. There’s an audience sitting on the floor behind him and a record player on the floor in front of him. The work’s title makes clear the power relationship between the speaker and the listener, and one can easily infer what’s bound to happen. In this early foray into live-performance, Ruggirello hired and directed the blindfolded young man into the space using his voice alone, then commanded him to smash the album (Reggae, Ruggirello is not a fan).

The black and white photograph of the installation Deux Jours shows four tape recorders topped with speakers, each placed on a tall spindly-legged pedestal. They encircle a smaller table set with a radio, a polaroid photograph, and a multi-plug. Each of the recorder stations is individually lit with a bulb that shines brightly in the image. The whole is staged in a narrow space that has a closed door at the back, and electrical wires snake from the ceiling to the stands and across the floor. The image is not very inviting because the space is so cramped, but the somewhat anthropomorphizing arrangement of the devices is appealing. Ruggirello explained that he recorded four people holding a dialogue that he wanted to play across the four machines in a coherent manner. However, the speed of the machines progressively desynchronized and the dialogue swiftly lost its meaning.

...desynchronization and synchronization of image and sound became lasting, guiding principles in Ruggirello’s video work.

Influenced by William S. Burroughs’ and Brion Gysin’s cut-up technique, in which new texts are composed out of fragments, desynchronization and synchronization of image and sound became lasting, guiding principles in Ruggirello’s video work. Take In-Out (1990) a dual channel video in which pairs of hands continuously swap everyday objects lifted from offscreen, or Paysage circonstanciel (1994), where objects you see falling on one television monitor provoke a channel change on the other, or Fade (2013), images of sunsets gathered off the internet that Ruggirello painstakingly joined at the horizon in one continuous montage. There’s a keen issue of timing involved in finding temporal equilibrium and disequilibrium in the gaps between images and sounds, and Ruggirello likes to use those gaps to generate meaning.

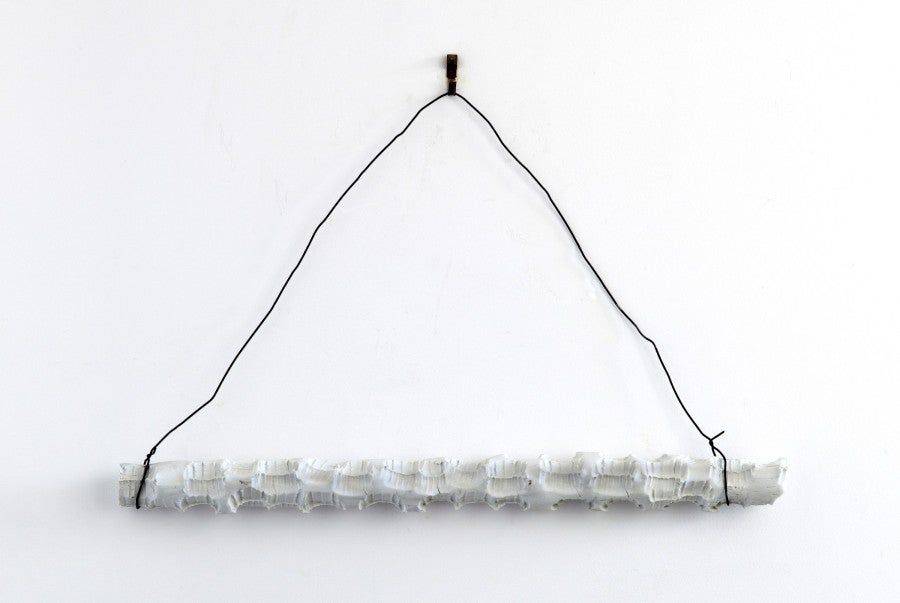

Guided by his commentary I started to see how technological advances shaped his process. I learned he has been teaching at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Marseille since 1999. He studied there, and in 1980, spent time in the atelier of Fluxus artist Claus Böhmler at the Hochschule für Bildende Kunst in Hamburg. He mentioned that access to different technologies and mixed-media practices when he studied in Hamburg contrasted sharply with his restrictive French art education, where he didn’t even have access to a camera, much less a recording studio. He learned to tinker with analog and digital systems, describing the video loop as a “veritable object of desire,” and work with what’s ready to hand. Over the past forty years, his materials have included: videotape, screens, overhead projectors, tape recorders, speakers, thorny acacia branches, ink, uprooted trees, clay, rice paper, curved sheets of metal, glass boxes, pixels, curved strips of wood, paint, automobiles, knickknacks, bees, light, a tortoise, garments, a snail, condensation, crickets, mice, kayaks, and shoes. In a 2011 interview he remarked: “I need an indeterminate mass in which I can cut, tear, zoom to extract a form, a noise, to make a decision, to produce cognitive short circuits. The studio is a space that creates the conditions of a perpetual cognitive bricolage.” After a few hours of cognitive bricolage with Ruggirello, I was saturated with input. I needed time for thoughts to settle and process before I could start writing. Specifically, I needed to try to come to terms with his assertion that his videos and installations, his use of montage and his selection and arrangements of objects, reflect his conception of an image “holding the possibility of a sculpture, of incarnating the same presence as a sculpture.”1

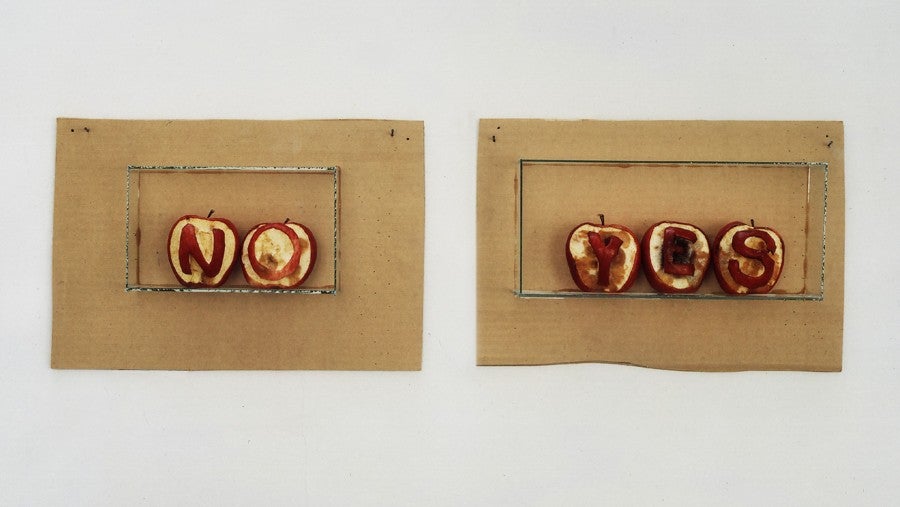

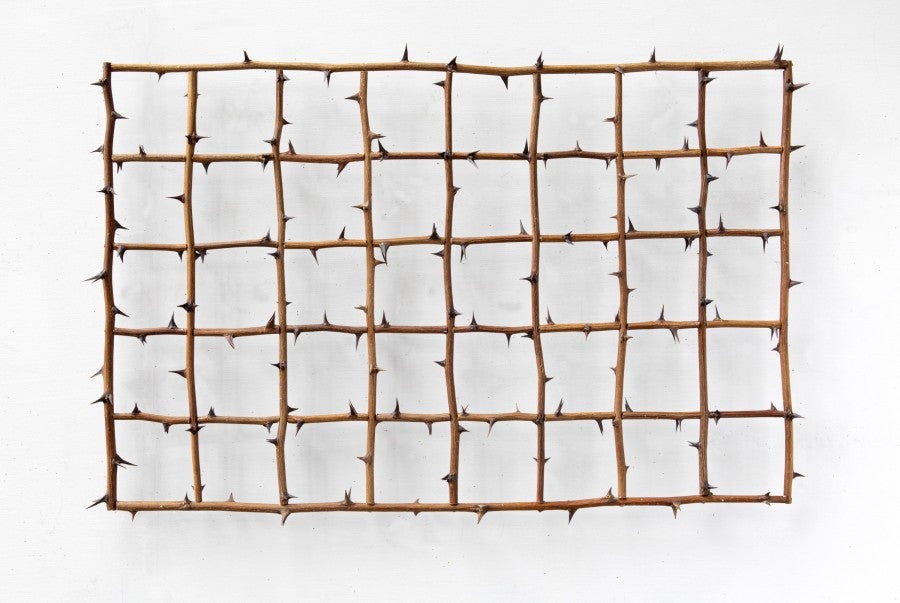

Countless artists since the 1970s have jettisoned an idea of sculpture reduced to the traditional materials and features one associates with the medium. Just think (obviously) of the sculptural hollow cone of light the 16mm projector throws from Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1970)! Exploring the interface between the image, performance, and sculpture, Ruggirello’s work in the 1980s incorporates recording and projection devices into sculptural installations that demarcate a territory in which sculpture intersects with other media and its environment, and in that way, it is very much of its time. But despite his foray into intermedial practices, sculpture conceived of as a three-dimensional object situated in time and space still features prominently in his work. Not unambiguously, however. Several titles of Ruggirello’s recent work indicate a tongue-in-cheek stance with respect to the contemporary history of sculpture and sculpture’s possible obsolescence. There’s the Crisis al Minimalismo series (seven wall pieces made from manipulated thorny Acacia branches between 2017-2019) and the bitten glazed porcelain pieces in the Mémorial for Body Art series (1992 and 2022).

Jean-Claude Ruggirello, King Kong, 1996, light projectors, motorized turntable. Muhka Anvers, 1999. Photo: Carine Demeter.

2.

It doesn’t seem incidental that Ruggirello titled his 2022 exhibition at the Galerie Papillon, which included sculptures, drawings, and video works from the 1990s up to the present, Lingua Morta, or Dead Language. The title Lingua Morta undoubtedly references Italian sculptor Arturo Martini’s 1945 screed against monuments Scultura, lingua morta (Sculpture, a dead language), written shortly before his sudden death.2 I couldn’t help but associate art historian and critic Rosalind Krauss’s influential 1979 essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” with Ruggirello’s practice. There, she outlines the “waning logic of the monument” that has occurred since the late nineteenth century and traces the expanded positions, beyond the monument’s fixed site in relation to public space, that modern and post-modern sculptors could henceforth explore.3 Krauss’s theorization of the medium as “a set of conventions derived from (but not identical with) the material conditions of a given technical support, conventions out of which to develop a form of expressiveness that can be both projective and mnemonic”4 has long resonated with me. I also couldn’t help but wonder, inconclusively, about possible ideological or historical connections between Ruggirello’s use of this title and current debates and controversies around decolonizing public monuments. My intuition that the connections are purely circumstantial was later confirmed when Ruggirello said he’s not interested in reducing his work to messages: “I am not interested in giving lessons, I’d rather create the conditions for another form of intelligence, for other cognitive circuits, to emerge in the face of my work.”5

Lingua Morta is also the title of a short video of Ruggirello’s shown at the 2023 International Film Festival Rotterdam, the second of his films to be featured there.

The video consists in a fixed shot of a horizontal procession of objects—a foam topped wine glass, a burning candle incrusted sideways into a rock, a polished pair of brogues chopped in half at the lace guard, a split wine bottle, a plaster cast hand flipping the bird—pulled, suspended, and levered by hooks and strings across a parquet floor, mostly from offscreen right to offscreen left. Ruggirello’s procession kicks off with the image of a crumpled white food wrapper resting atop an object, both of which are pulled by different strings, one white, one brown. The brown string tugs the paper away, the white string stays tautly attached to a rough clay reproduction of a well-known image of Joseph Beuys (from in his iconic 1974 performance I like America and America likes Me) that shows the German artist wrapped in his signature felt with curved cane aloft, attempting to commune with a coyote. After a second, the miniature Beuys slides away.

The pulled and manipulated objects make the noises you’d expect, but the synchronized sound rings as if dramatized, and added post-production. There are moments of humor and a few visual surprises: a splodge of foam magically disappears right before it gets squashed by a hag stone; a pair of men’s arms strenuously handstand walk across the parquet right after a pair of truncated porcelain dog legs pass by in the opposite direction. Just as you get used to the video’s structure, and your attention starts to predict that a new item will appear from one side, Ruggirello inserts a twist that thwarts your anticipation. Lingua Morta closes ceremoniously with a knobby suspended rock extinguishing a taper candle, momentarily recalling the candles aflame in numerous Gerhard Richter paintings. The final image, especially in association with the Beuysian grand marshal, tempts one to interpret the cortege as a memento mori, a reflection on the death of sculpture, or a certain idea of sculpture as a site-specific, material bounded, three-dimensional static form, and, in any case, as a marker of the passage of time.

Jean-Claude Ruggirello, Lingua Morta (extract), 2020, video and sound, 11 min. Courtesy of the artist.

3.

Ruggirello’s editing of shot and found footage hints at narrative but is perplexing.

Lingua Morta’s pace and rhythm lull you into a false sense of spectatorial security. Its surreal juxtapositions only occasionally raise your eyebrows. In contrast, Ruggirello’s 2021 video Bruits de fond thrusts you into a bizarre scene of unhurried commotion. After an establishing exterior shot of a blossoming tree followed by an interior shot of hands struggling to open a padlock, we cross the threshold to witness an upheaval in the making. A dapper white-haired gentleman wanders like a confined bird in an apartment, his nose frosted from the fraisier cake he keeps nibbling from his hands but seems to find hard to swallow. Art hangs on the walls: a drippy scribbled painting of a bright pink dick, a Morandi still-life reproduction, a painted three-quarter portrait of a woman, another female portrait surrounded on either side with paintings of fried eggs. The real and portrayed natural world is also visible but contained: a foliage filled trompe-l’oeil wallpaper provides fake perspective, a nature program about primates plays on the tv screen, flowers are tucked into vases on the dining table set for a meal, as well as on various side tables, and a tree stands alone in the loft-like space.

The gentleman proceeds to remove a flat brick from the refrigerator and lobs it onto the table, the first in a series of deliberate, repetitive gestures of object-led demolition, that cause the apartment to become filled with shards of detritus, puddles of liquids, smears and smudges of food, torn fabric. Crickets invade in a haphazard, cockroachy way, a poor tortoise appears, struggling to right itself, chimps screech noiselessly from the tv. Now and then, cutaway shots introduce younger male characters, weirdly laughing, grossly feeding themselves and licking food off fingers or gesturing ostentatiously. Rising water surrounds a bald male head encased in glass. Ruggirello’s editing of shot and found footage hints at narrative but is perplexing. Are any of these secondary, “offscreen,” actions “real” or are they all in the protagonist’s mind? Meanwhile, throughout the video, an off-key cello plays a languid tune. Crunching and spilling and whipping background noises that don’t necessarily cohere with the action augment the tawdry atmospheric confusion. The gentleman concludes his calamitous shuffle by taking a seat in the easy chair facing the television. That destruction is an additive and cumulative process is one clear interpretation of this work. Others are so ambiguous they might as well remain secret, subject to plausible deniability.

Jean-Claude Ruggirello, Bruits de Fond (extract), 2009, HD video and sound, 19 min. Private collection. Photo: EMaillet . Steve Calvo.

“Like a lunatic you endure the day with ceremony.”6 This phrase echoed later with my experience watching Bruits de fond. In an episode of our months-long conversation, Ruggirello recommended I watch the 1960 film The Savage Eye in connection with his practice. It was Edward Hopper’s favorite, he remarked. The line from the film is delivered by the male disembodied narrator, credited as “the Poet,” to the female protagonist Judith, whose marriage has recently fallen apart. Left cynical and disoriented by her husband’s affair, Judith succumbs to an existential crisis in 1950s Los Angeles, filmed in a ruthless documentary style. While living on “bourbon, cottage cheese, and alimony,” she converses with the omniscient voice in her head. The aged male protagonist of Bruits de fonds could also be seen as enduring his day by enacting a ceremony of premeditated decomposition. Or he could just be an artist rehearsing a performance. Watching the video over and over, pausing it to focus on details, I endured moments of revulsion and feelings of distaste, and grappled with my own spectatorial blind-spots, including a gender-bias against this male artist’s view on a man’s world. I must withstand all this again as I undertake the durational ceremony of writing about Ruggirello’s work. Then again, isn’t enduring the day with ceremony, whether with lunacy or without, an apt enough description of what we do when we try to maintain a creative practice, like making art, or like writing?

Lingua Morta and Bruits de fond both feature works Ruggirello has made or elements of his work in a death parade and ruinous ritual, but he still has a stake in keeping sculpture alive and kicking. He insists that whenever we think, say, or do anything, we produce a “hors-champ,” or something off-screen, out of shot, unseen, out of range and that this is his primary interest in images and in sculpture. He illustrates this with his work Martingale (2007) a dual screen video projection portraying a slowly spinning, horizontally suspended, customized sports car paired with a slowly spinning, horizontally suspended, uprooted autumn-leafed tree.

Jean-Claude Ruggirello, IN OUT (extract), 1995, video and sound, two screens and two video players, 7 min loop. Collection of Musée de Nantes.

“Why shouldn’t sculpture move?”

Here Ruggirello claims the projection approximates sculpture by virtue of producing space and capturing time. It produces space and captures time via the “hors-champ” that literally surges in the windscreen’s reflection as a secondary image. The “hors-champ” also appears the moment the top and the base of an uprooted tree enter the line of the spectator’s vision. The top and the base of the uprooted tree, usually hidden to our field of vision, also represent the sculptural blind spot (l’angle-mort). Statements like these about sculpture and video get repeated in the interviews and texts about Ruggirello’s work. Whenever I tried to clarify what he means when he says the video image is akin to his conception of sculpture, his explanations took a speculative turn. “There’s a porosity between the materials I use,” he said, “and the objects emit a frequency, a kind of telepathic wavelength.” This reminded me that Joseph Beuys once said: “for me the formation of the thought is already a sculpture.”7 More practically, Ruggirello asserted “why shouldn’t sculpture move?” Indeed, why not? Sculptures often do. Consider Lastream (1996), a video loop composed entirely from close-up footage of crunched up food wrappers and other sorts of packaging unfolding and unfurling, each used and crumpled wad taking its own sweet time to emit cacophonic, crackling sounds.

Ruggirello’s non-video series “Etudes des trous” (2018) seems to similarly want to capture and portray sculptural relationships between spaces and times, to test the relative frequencies of objects. He inserted colorful inflated modelling balloons into the ancient holes that water and time have eroded into hag stones. The hole study gets “activated” by the progressive deflation of the balloon; the juxtaposition of two materially and temporally distinct elements creates the conditions for the sculpture to exist, but the co-dependency of the materials is what causes the sculpture to mean something (let’s bypass the penetrative sexual connotations, too obvious to linger on). To better make a point I was struggling to grasp in a phone call we had while he was in Rome visiting the Vatican museum, Ruggirello sent me a photo he had taken of a detail from a Bernini portrait bust of Cardinal Scipione Borghese. The detail shows two buttons on the cardinal’s robes, one of which is coming undone or has been poorly fastened.

According to Ruggirello, Bernini’s decision to sculpt imperfection, to portray the flaw, highlights the sculptor’s finesse, but also captures a sense of movement, of embodied gesture, caught in a moment. I study the picture. “Maybe it also catches a moment of indecision,” I think. In relation to one another, the two buttons produce a kind of recursive ground of signification, loaded with potential meaning. Scrolling and clicking and zooming into images in folders on my computer desktop, I’m left wondering whether such a recursive ground of signification could be similarly located in Jean-Claude Ruggirellos’s expanded intermedial field of sculpture, this modular space-time environment replete with objects and images whose projective and mnemonic capacities he seems to need to reject, yet keeps returning to, like a detectorist. What do you think? Convinced?

Epilogue

The first time I ever heard of Jean-Claude Ruggirello was when TextWork invited me to write about his work. I am certain we had never encountered each other during the decade and a half I lived in Paris, the location of his gallery and where he is partly based. Some quick online research reassuringly presented an artist who has been working across media (video, sculpture, sound, drawing, installation) for forty years. Based on the duration of his career alone, which developed during the heyday of Western postmodernism and persists in our pluralist, globalized present, Ruggirello appeared to be someone with a confident practice, routines established and tweaked, consistent opportunities, and materials deployed in ways I thought I could relate to.

The matchmaking process that TextWork is founded upon, whereby international writers are commissioned to write about artists of the French scene they are unfamiliar with, felt fraught to me from the outset, in part because of everything I didn’t know and everything I couldn’t possibly get to know about this artist in the limited time I have for writing parallel to a full-time job in art education. I don’t get back to Paris much, and most of what I would learn about Ruggirello’s long artistic career would have to stem from my (unreliable) analysis of slews of digital files consulted at my desk rather than from sustained first-hand encounters with his considerable oeuvre. What emerged throughout this hyper-mediated telematic process of learning about Ruggirello and his work was an unsettling feeling of deep (affective and cognitive) ambivalence about interpreting his output and producing this text. By ambivalence, I mean classic ambivalence: mixed feelings coupled with simultaneous attachment to multiple objects or objectives and an incapacity to choose between them, the kind of ambivalence that Paul Eugen Bleuler in 1910 considered a symptom of schizophrenia, but which is no longer psycho-pathologized as such.

As an art writer, one might cope with ambivalence and avoid the sort of equivocation that delegitimizes critique by doing a close reading of the work and the discourse that surrounds it, or by swiftly attempting to establish an order, by genealogically classifying and situating the work in relationship to a broader context. One might nudge it into a cozy literary or theoretical framework, maybe one that has been hinted at by the artist or offered by a curator of that artist’s exhibition. In the face of interpretative insecurity, I turned to the late Eve K. Sedgwick’s essay, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay is About You,” which offers an analysis of critical modes that became standardized in literary and cultural studies, that have a parallel in contemporary art writing too. There she traces a defensiveness and suspicion at the heart of what she calls “paranoid” interpretations of culture that aim toward some sort of mastery of a subject. She advocates for a reparative approach to reading that centers hope and surprise as the reader “tries to organize the fragments and part objects she encounters and creates.”8 I’m not sure, but in finalizing this essay I’ve come to think that ambivalent reading could be situated somewhere between these two poles.

As I approached this text work, I struggled to figure out how to focus on the fragments and parts or consider the generalities of Ruggirello’s output when experiencing such a large collection of it as data on a screen, from a distance. Without being able to trust my felt experience, my habitual, embodied, solitary (or social) way of experiencing visual art, without the circuitous dance it sometimes incites me to do, I got stuck at my desk and in my head. Banging around up there, I also had to contend with the fact that these days many of the epistemological, methodological, and classificatory modes for experiencing, thinking, and writing about art have been thoroughly examined, criticized, and found wanting. Furthermore, contemporary art world pre-occupations (with, say, identity politics, collective and community art practices, blockchain and NFTs or Artificial Intelligence) are not those of Ruggirello. Out of necessity, I’ve opted for an ambivalent reading that sits uncomfortably and with uncertainty about what I can know about this artist's practice and how I can describe and interpret it. I hope this ambivalent reading does some justice to the persistent ambiguity I sensed about the status of sculpture in Jean-Claude Ruggirello’s work.