On a frigid January afternoon in London, Julie Béna and I took a walk around Bunhill Fields Cemetery, located just on the fringes of the buzzing Shoreditch district. Encircled by the towering uniformity of glassy office buildings, hipster-filled bars, and commercial Food & Beverage chain businesses, I was surprised at the silence that the contemplative space offered; a welcome respite from a city’s pulsating expectancy. In the cemetery, the seemingly endless routines of work, satiation, and leisure seemed to be suspended and revealed as existential façades. After a pensive stroll, we encountered vested caretakers who were wrapping tombstones in blankets, as if to keep them warm – a tender, considered, if not poetic, gesture that disrupted the city’s alacrity and regularity. This was, they said, part of a conservation process.

For the French historian Michel de Certeau, normalized everyday practices (like walking, reading, or talking) can be tactically reconfigured. These seemingly banal and ignorable practices are far from passive acts of consumption. For instance, readers do not necessarily obey the logic of sequence. Their eyes often improvise and “drift across the page.”1 Similarly, city commuters often demarcate their own ambulatory paths which stray from those dictated by urban planning. Although, as de Certeau argues, these commonplace activities “remain subordinated to the prescribed syntactical forms” and establishments, they also readily “trace out the ruses of other interests and desires that are neither determined nor captured by the systems in which they develop;”2 reminiscent of the deliberate acts of slowness and care by the tombstone conservators in Bunhill Fields Cemetery. Likewise, the politico-capitalistic truancies that de Certeau outlines manifest themselves in Béna’s works, which, in her words, propose “different methodologies to slow down and pay attention to invisible mechanisms in our everyday lives.”3 Our brief stroll through Bunhill Fields proved illustrative of some central concerns in her work, for instance, her concern with alternative rhythms, practices, paradigms, bodies, and sentiments that may go neglected or unnoticed.

Jesters and Prophets

The cemetery is located at a walking distance from Kunstraum, a non-profit art space that engages with its surrounding neighbourhood, comprised predominantly of public housing units. Given the Kunstraum’s penchant for exhibiting experimental performance and time-based artistic practices, it is apropos that Béna had inaugurated her first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom there just the night before our walk in the cemetery, as her practice originates from performance and finds productive and intriguing tributaries in video, animation, sculpture, installation, and research-based texts. Béna’s exhibition at Kunstraum was inspired by the potent liminality of the Bunhill Fields Cemetery, where William Blake and thousands of other nonconformists, writers, and radical thinkers like Daniel Defoe and John Bunyan are buried. The exhibition featured a new installation and animation film titled The Jester and Death (2019): a sequel to Anna & the Jester in Window of Opportunity (2019), which was exhibited in 2019 as part of Béna’s solo exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, Paris.

In these multimedia works, Béna strategically deploys the jester as a double, an avatar, a deceptively light-hearted substitute through which she critically comments on social and political issues. The jester’s jokes, playfulness, and humour are tactical proxies through which Béna sublimates urgent and serious topics including, but not limited to, gender and sexual politics, socio-cultural hierarchies, precarious labour, and the insidiousness of cultural commodification. In his play King Lear, Shakespeare conjectures that “jesters do oft prove prophets,” referring to the instructiveness of a jester’s seemingly inane behavior. Jesters often straddle the fine line between comedy and tragedy, serving as secondary foils to a narrative’s protagonists. But it is precisely their foolishness that uncovers social mores and directs viewers to the moral of the story.

...what is more indicative of capitalistic speed and excess than the sports car, a paradoxical Futurist symbol of death and progress?

Béna’s representational astuteness with regards to the jester’s didacticism is evident in the animation of The Jester and Death, in which we witness the Jester and a virtual version of William Blake participating in a drift-car race in the Bunhill Fields Cemetery. The digital rendering of this outlandish scenario lends a sense of levity to any pensive nihilism that viewers might anticipate; the bombastic flashiness of the spectacle belying Béna’s social commentary. As in Bena’s other exhibitions, the presentation of The Jester and Death in London is accompanied by sculptures and installations; in this instance, miniature jester puppets strung up on the wall behind the video projection, lit by the ominous glow of a lamp placed on the floor, and an electric green model of the sports car featured in the video, which doubles as a seat for visitors.

In the animation, the jester, dressed in a skintight seafoam jumpsuit adorned with a ruffled white Victorian collar, encounters three non-human interlocutors – a snail, a fly, and a spider – that narrate original texts written by Béna. The trio of creatures play a round of ‘Guess who?’ with the clueless jester. From their enigmatic hints, viewers may or may not discern that the desired answer of the perceptibly frivolous game is Death, the artwork’s portentous spectre. When the Fly offers yet another philosophically dense clue – “From yesterday to forever, you can’t order it!” – suggesting the unpredictability and absoluteness that is the advent of death, the jester simply replies with facetious puns. She asks: “not even with UberEats? Deliveroo? Amazon?”, much to the chagrin of her non-human companions. Moreover, what is more indicative of capitalistic speed and excess than the sports car, a paradoxical Futurist symbol of death and progress? In The Jester and Death, philosophy is debased by crass commodity; the exclusivity of thought interrupted by humour. Soon after, the jester is kicked down a hill by Blake, cementing her delinquent personification. In this work, Béna, through the jester’s mocking of philosophical writings and ironic references to delivery enterprises, adeptly satirizes the superficiality and capitalistic dependency that plagues contemporary society.

The non-human creatures in Béna’s works – typically considered by human beings as insignificant things to be squashed – are given agency and depth. The category of the ‘human’, so fiercely policed by humans themselves in order to hoard some semblance of species superiority, is debunked in Béna’s video. As theorist Mel Y. Chen argues, animality often “bleeds back” into humanness, and has long served as an “analogous source of understanding” for human behavior.4 Furthermore, animality and other non-human vitalities are often deemed “deathly, or otherwise “wrong”,” their value to humanity not recognized and insistently diminished.5 Despite being demarcated as dead, sterile, unfeeling, unthinking, and even immoral figures, the snail, fly, and spider who inhabit the virtual Bunhill Fields Cemetery in The Jester and Death are presented as erudite beings, their consciousness disconcerting their seemingly fitting placement in a space of death. In Béna’s practice, joviality and humour, conveyed through the figure of the jester, provide a clever counterpoint to foreground the expanded capacities and political ecologies of interconnection of other non-human and marginal bodies.

“She became me, and I became her”: Fake and True

Like other works in her oeuvre, The Jester and Death elucidates some pertinent issues that Béna tackles through the comic relief of the jester-as-double. In an interview with curator Laura Herman for her exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, Béna articulates that “the idea of the double—what is hidden or revealed, what is “in front” and “behind” the stage—was [her] reality until [she] turned 25 years old.” Béna’s interest in chameleonic personalities began from childhood. She was an actress from the ages of 4 to 15, balancing school in the day with theatre performance at night. Later on, as an adult, Béna studied at Villa Arson, a fine art school, while working night shifts as a barmaid in clubs to support herself. For Béna, these personae were “inseparable…invisible to each other and nonetheless dependent on each other for their existence.”6

Uncoincidentally, in her practice, Béna transforms into different characters and inhabits expanded worldviews and narratives. As identities become increasingly politicized and polarized, and with good reason, Béna’s practice is a timely reminder to maintain the fluidity of subject positions. Labels, often used for reductive promotional branding, are not as interesting to her as effusive and complex expressiveness. For example, in Have you seen Pantopon Rose? (2017), a video work that originated from an eponymous performance, Béna theatrically re-enacts the character of Rose Pantopon, a minor, forgotten protagonist in William S. Burroughs’ novel, Naked Lunch. Mentioned only in a single sentence in Burroughs’ novel, Béna took notice and delved further to discover who this inexplicable character was, who she could be. Over Skype, Béna tells me that “she became me, and I became her.”7 Personas were mixed: one real and contemporaneous, another fictional and from the past. Reality and surreality are separated by nary a sliver of existence. But are these divisions as concrete and absolute as we think? In the video, Béna brings to life a mute Rose Pantopon, symbolically silenced in history’s records. As a choir of three performers asks her probing questions, Béna, embodying Pantopon’s historical erasure, pantomimes with exaggerated facial reactions and a plastered, enthusiastic grin, rather than responding straightforwardly with words. Advertisements marketing glossy condominiums intersperse these questions, their hyper-smooth sheen underscoring Béna’s saccharine embodiment of Rose Pantopon.

What does this seemingly perfect veneer conceal? Teasingly, the final interviewer asks Rose/Béna: “How do you know I’m real?”, responding to her unanswered question with an equally cryptic claim: “I’m not real. Just like you Rose. I come to this reality. You came for a dream. A time ago.” Reality as a singular phenomenon does not hold steady in Béna’s practice. Dancing robotically in a black jumpsuit, Béna and an invisible narrator repeatedly sing that Rose Pantopon is “not a trick…not a song…it’s a mirage.” Similarly, in Anna and the Jester in the Window of Opportunity, the Jester is a representational proxy for a combination of two figures: Béna herself and Anna Morandi, an 18th Century anatomist and wax modeler. Béna first encountered Morandi’s wax sculptures at the science museum of the Palazzo Poggi in Bologna. Speaking about this particular manifestation of the Jester, Béna ponders: “Anna and the Jester function as one and the same person. Sometimes I wonder if Anna is the Jester, and the Jester is Anna, and if I’m the Jester, then who is Anna? Am I finally Anna?”8 Is one more ‘real’ than the other?

What is worth noting in relation to Béna’s approach is the inevitable crossover between ‘real’ person and fabricated personality

Analyzing the role-playing website and virtual community LambdaMOO, which was founded in the early 1990s, Lisa Nakamura observes how participants were “required to project a version of the self which is inherently theatrical,” leaving their “’real’ identities…unverifiable.”9 Through textual self-descriptions, users could project a virtual self and reality that was completely separate from their lived experiences, begging the unsettling question of a commixture of personalities. While Nakamura’s study focuses on racial passing and caricatures, what is worth noting in relation to Béna’s approach is the inevitable crossover between ‘real’ person and fabricated personality, and the indistinguishable line where real meets virtual and authenticity stumbles on fakeness.

A constructive uncertainty abounds in Béna’s works about who is speaking and who is present. In her feminist theoretical proposition for “teletechnology,” Patricia Clough describes the collective force of poststructuralist criticisms toward the undoing of cultural binaries (human/machine, nature/technology, real/virtual, living/dead, and so on). For Clough, however, “the deconstruction of essentialized identities nonetheless produce[s] a desire for…a politics of identity.”10 In other words, Clough warily broaches an important, and perhaps unsolvable, conundrum around visibility: an identity needs to first be specified before it can be deconstructed, unpacked, or annihilated. To disappear into another’s flesh, mind, and experience, one must first be interpellated as knowable and knowing subject.

Shininess

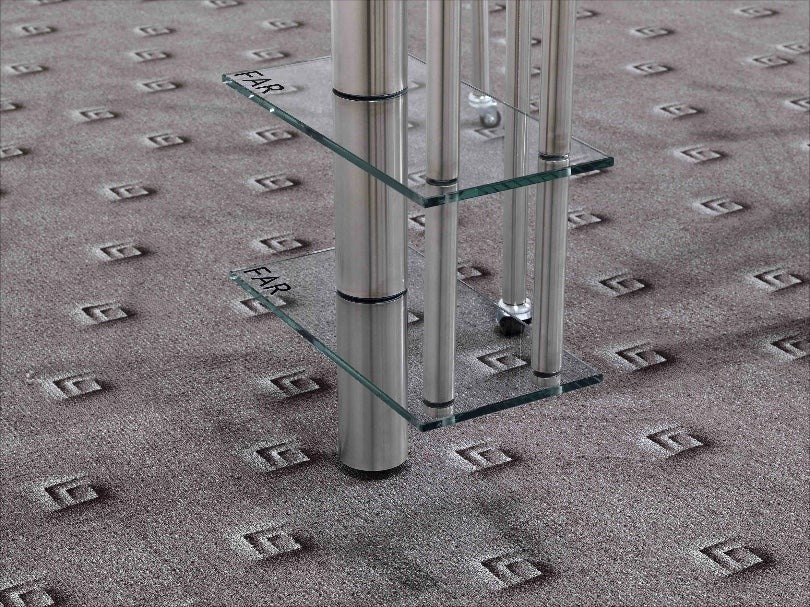

Behind a façade of shine, mechanical beauty, and perfection, Béna intricately weaves together different cognizant selves, literary narratives, and asynchronous temporalities, using storytelling as a means to question where authenticity, authority and power lie. This aesthetic strategy is evident in the animation for Anna and the Jester in the Window of Opportunity, which features Opportunity, an elaborately designed corporate glass desk against which the video’s narrative unfolds. As with the installation components of The Jester and Death, Opportunity exists both IRL (in real life), and in virtual form. Béna’s exhibition at Jeu de Paume was accompanied by a life-sized glass table model. However, in the animation, the table is an entire universe which the Jester traverses on her adventures: she ascends the table’s gargantuan legs, which are transmogrified into stainless steel elevators, and slides down pristine tubes as if on a slide. Through digital animation, a functional table is transformed into an endlessly expanding skyscraper, an entire terrain to be explored.

Béna brings to the fore characters, bodies, and personalities that have been historically marginalized, and grants them complexity and agency. This digital rendering of Opportunity houses the Mermaid, the Groom, and the Cyclops: three of the jester’s interlocutors in the video who are modelled after Morandi’s wax fetuses of stillborn or biologically deformed babies. The Mermaid, for instance, is a floating apparition with a tail, the Groom has two extra pairs of hands, and the Cyclops a shiny reflective gazer for eyes. But rather than fixate on or exoticize these differences, Béna gives voice and form to forgotten, unwanted, and invisibilized figures who are unassimilable by society’s normative standards of being. Digitality proves a useful medium where the excitement of subjective ambivalence and plurality plays out. Béna says of her animated characters like the jester: “I didn’t want to embody them or to project them into the “real world.”…[Through animation] I could make them speak and act but they would always remain somewhere else, in their own world.”11 Reminiscent of Nakamura’s argument, the digital realm, rather than a ‘real’ life of flesh and bodies, has the potential to be a social arena, a place of greater subjective possibilities and interactions.

Digitality therefore allows Béna to represent bodies and worldviews that do not yet exist within comprehensible and narrow categories. Ascending in an elevator with the jester, the Groom muses about existential questions: “Does the existence square with the prior understanding of the subject? Have you stretched your existence enough to help you solve your problem?” These esoteric questions shore up Béna’s fruitful use of digital technology as an artistic medium to expand the registers of visual representation to include non-normative subjects. Opportunity, a matrix perceived to be utilitarian, industrially and efficiently produced, and regularized, in fact allows multiple possibilities and is inhabited by bodies that have been ostracized by the dictates of society. Glass, once clinically exclusionary, now becomes a home for Others.

Speaking about this work, Béna says: “I offer you something shiny to show you what is fucked up. I offer you some comedy to show you a tragedy. I’m always interested in this double bind.”12 The blindingly bright and reflective glass surfaces of Opportunity come to mind. For historian Tom Holert, shininess is “characteristic of surface effects, of glamour and spectacle.” It “pretend[s] transparency while offering glistening opacity.”13 The asinine exclusivity of superficiality-as-aesthetic warrants attention and analysis. Glass is emblematic of this paradox. The material of choice for corporate skyscrapers, like those that glimmered condescendingly above the unassuming Bunhill Fields Cemetery, glass reveals as much as it conceals. Its material transparency gives only an appearance of accessibility, truth, and authenticity, while blocking access to the inner workings and hierarchies within the structure itself. In Anna and the Jester, Béna turns this paradigm on its head: revealing glass and its infinite transparency as conditionally opaque, using it to house the very entities that it keeps out of its border.

Disobedient Desires

...desires, sexualities, and eroticism can also be produced, not just material things or goods.

What bodies are allowed to speak? In what form, context, and with what lexica? These are some key questions that come to my mind when experiencing Béna’s artworks. These tensions of visibility and articulation are brought to bear in Who wants to be my horse? (2019), a video work featuring five performers whose soliloquies, musical performances, and theatrical recitations express pluralistic perspectives of sexuality and bodies. In this work, the impulse for recognition meets a creative desire for complexity. Master of ceremony Shanta Rao begins by proclaiming that “each minute [of this experience/video] will be a minute of pleasure,” there will be “partners with free hands and free mouths.” Noticeably, Rao does not list biologically essentialist tropes of sexuality, for example, by talking about genitalia. Instead, she suggests an openness and liberal reterritorialization of bodies reminiscent of Paul Preciado’s dildotectonics, wherein he proposes alternative erotic scenarios and “deviant and non-normal uses of the individual body.”14 Analyzing the work of Elizabeth Grosz and Deleuze and Guattari, Clough conveys that “bodies are what desire assembles in order to do something.”15 They are not empirical entities affixed to certain registers of knowledge. They can be readily reassembled to suit stray and individual urges. Through the juxtaposition of discursive feminist texts, delivered as soliloquys, and the explicit portrayal of bodies, Béna strategically plays upon the currency of sexuality to address the expansiveness of desire and eroticism.

Through their performances, which range from rope-tying to musical compositions and spoken word, the actors in Béna’s video work itself complicate any superficial impressions that audiences might have of their personas and bodies. Madison Young, one of the key performers in Who wants to be my horse?, was a superstar of early 2000s American BDSM porn. In the video, Madison muses on sexual possibilities of scenarios such as having swingers as neighbours or setting up a nude housecleaning business, proceeding to expertly tie herself up with rope; her physical exhaustion becoming more apparent as time passes.

Upon first viewing, Young might be perceived as straightforwardly re-enacting and conjuring a voyeuristic sexed experience. However, through the abovementioned cues, she touches upon the sexual economies of labour that underpin Béna’s practice and the broader field of gendered work and precarious artistic labour. Discussing the post-Fordist labour of Bangkok’s exoticized ‘pussy shows’, Ara Wilson states that “capitalist modes of accumulation have always been intertwined with modes of intimacy and pleasure.” Wilson argues that “subjectivity (knowledge, desire, affect) has become itself productive, not merely co-opted by capitalism, but immanent to it.”16 In post-Fordist frameworks, desires, sexualities, and eroticism can also be produced, not just material things or goods. Young’s literal, corporeal exhaustion from her self-constriction with ropes, for instance, makes apparent to audiences the ineffable labour required to generate her sexual currency.

In his book Testo-Junkie, in which he recounts his year-long experience on an unapproved self-prescription of testosterone, Paul Preciado writes that “the real stake of capitalism today is the…entire material and virtual complex participating in the production of mental and psychosomatic states of excitation, relaxation, and discharge.”17 In his biopolitical analysis, Preciado argues that the neoliberal pharmaceutical industry produces rather than provides for transgender subjects, regulating their dependency on essential, life-giving drugs like testosterone. For instance, testosterone should not be dispensed to those assigned female at birth, or genderqueer and non-binary people who do not wish to undergo sex reassignment surgery. By (mis)using testosterone and experimenting on himself without an end-goal in mind, Preciado asserts his subjective agency through what he calls a “micropolitics of disidentification,” subverting the dictated usage of the very molecules meant to produce and control a whole host of bodies.

Similarly, like Young, Béna, who performs in many of her own videos, is very conscious of her self-presentation, (self-)exploitation, her navigation within a seemingly hierarchical power dynamic, and the labour-intensive preparations for her performances. In the Netflix documentary After Porn Ends Part 3 (2018), which follows the lives of ex-porn stars, one performer wistfully ruminates that “the Internet is completely and totally forever, and you can’t take it [explicit depictions of yourself] back.” Others echo this sentiment. Hotel heiress and 2000s icon Paris Hilton, arguably the (unwilling) originator of the celebrity sex tape genre, recently confessed that she “thought everything was taken away from [her]” when her now infamous sex tape, 1 Night in Paris, was distributed without her prior consent and proliferated into an eternal invasion of privacy. Instead of viewing exposure and precarity as permanent insult and injury, a loss of power and agency, Béna and the performers of her video underscore Wendy Chun’s theoretical proposition for the right to loiter, to be publicly seen, and to engage with a “multitude of exchanges,” physical, virtual, sexual, or otherwise.18 Like Chun, Béna in this video work mobilizes the openness of orifice and nudity as avenues to channel radical sensitivity and feminist community building. Virality, of sex or contagion (at the point of writing, the COVID-19 coronavirus has elicited global and regional panic and re-ignited racial vitriol), can present opportunities for collective action rather than encourage the perpetration of paranoid persecution.

Tentative Forms

...“in retelling the origin stories, we will learn to subvert the myth.”

As Young performs, she recites a script written by Béna, which was influenced by Donna Haraway’s seminal essay A Cyborg Manifesto, in which Haraway argues for the “pleasure in the confusion of boundaries” and demystifies the “belief in the “essential” unity” of identity.19 At the end of her monologue, Young surmises that “in retelling the origin stories, we will learn to subvert the myth.” In Who wants to be my horse?, performative repetition engenders productive difference, not a stalemate of identity. Béna is introduced by artist Dita Lamacova with the refrain: “This woman may look like Julie Béna, and act like Julie Béna. But don’t let that fool you, she really is Julie Béna.” The other performers are ushered into the frame in similar fashion. These tautological articulations achieve the opposite of their desired effect: the concerted efforts at self-consecration may ironically backfire, leading the spectator to question the reality of the persons, stories, and situations presented in the video. Analyzing Judith Butler’s “notion of performance [that] refer[s] to the body as an imaginary matter,” Patricia Clough speculates that the intervals between the performative repetitions of identity present “risks and excess” which “threaten to disrupt the identity being constituted.”20 For Butler, “bodily matter is dynamic, more an event or a matter of temporality.”21

This tentative in-betweenness lends itself as an enriching force of destabilization in post-porn politics, a sex-positive, feminist movement and important source of theoretical influence for Béna. Elizabeth Stephens, artist and partner-collaborator to Annie Sprinkle (who incidentally wrote the foreward to Madison Young’s memoir, and whose texts Béna also draws influence from in the video), opines that “if post porn really has a political dimension it should include any age, race, and gender. Today you can see porn imagery of every kind of body on the Internet.”22 The virtual space of online networked technologies changes the relations between bodies, the associative links between a body and its cognisant inhabitant self, and the very naturalised constitution of bodies as a whole. Extrapolating these sentiments as an interpretive lens, Béna’s artworks can be viewed as a practice that creates alternative imaginaries of the body that embrace pluralistic notions of desire, vitality, and value. Peeling back their surfaced treatments, Béna’s personae and characters reveal layers of representation that attempt to confound a quintessential form of identity.

Certeau, Michel de, The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988, xviii.

Ibid.

Transparent surfaces, opaque bodies, A conversation between Julie Béna and Laura Herman, in Julie Béna, Anna & the Jester in Window of Opportunity, Jeu de Paume, Paris, CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux & Museo Amparo, Puebla, 2019, p. 23. Available on www.librairiejeudepaume.org/ebook/9782915704860-julie-bena-anna-the-jester-dans-la-fenetre-d-opportunite-laura-herman-irene-sunwoo/

Mel Y. Chen, Animacies, Duke University Press, 2012, pp. 89, 99, 102.

Ibid, p. 2.

Béna and Herman, Julie Béna, Anna & the Jester in Window of Opportunity, p. 23.

Skype conversation with the artist, November 2019.

Béna and Herman, Julie Béna, Anna & the Jester in Window of Opportunity, 27.

Lisa Nakamura, Race in/for Cyberspace: Identity Tourism and Racial Passing on the Internet, in The Cybercultures Reader, Routledge London 2000, p. 297.

Patricia Clough, Autoaffection: Unconscious Thought in the Age of Teletechnology, University of Minnesota Press, 2000, pp. 138-9.

Béna and Herman, Julie Béna, Anna & the Jester in Window of Opportunity, 25.

Béna and Herman, Julie Béna, Anna & the Jester in Window of Opportunity, 21.

Tom Holert, “Politics of Shine,” E-Flux Journal, January 2015. Accessed on www.e-flux.com/journal/61/60985/editorial-politics-of-shine/

Paul B. Preciado, Contra-sexual Manifesto, Opera Prima, Madrid, 2002.

Clough, Autoaffection: Unconscious Thought in the Age of Teletechnology, pp. 132-3.

Ara Wilson, “Post-fordist desires: the commodity aesthetics of Bangkok sex shows,” Feminist Legal Studies 18(1), April 2010, p. 57.

Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, Feminist Press, 2013, p. 39.

Wendy Chun and Sarah Friedland, “Habits of Leaking: Of Sluts and Network Cards,” differences Vol 26, No. 2 (2015): p. 19.

Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto, Socialist Review, 1985, p. 16.

Clough, Autoaffection: Unconscious Thought in the Age of Teletechnology, p. 120.

Ibid.

Elizabeth Stephens, Annie Sprinkle and Cosey Fanni Tutti: Post Porn Brunch, in Post Porn Politics; Queer_Feminist Perspective on the Politics of Porn Performance and Sex_Work as Culture Production, B_Books, Berlin, 2009, p. 99.