1.

Many of Tatiana Trouvé’s drawings, sculptures, and installations seem poised on the razor edge of elegance and restraint. Immersive, even when they hold us at a distance and don’t allow us to enter, there is something unsettling about the spaces she creates, which seem to place you in the middle of a moment that is already over. Reflections on time, space, and memory course through these works, which open interstitial perceptual zones that collapse notions of interior and exterior, the personal and the universal, reality and fiction, dreams and waking life. It’s fitting, therefore, that my own encounters with Tatiana Trouvé always seem to unfold in states of exception. When I first visited her studio in Montreuil in 2018, I had a searing pain in my throat and had to ask the simplest and most straightforward questions I could to avoid having to speak too much myself. Fast forward two years later and we meet again, this time through a screen in the midst of a global pandemic. By the time that we sat down together virtually in May 2020, the craze of disinfecting one’s groceries had passed but life certainly hadn’t resumed its normal pace. News changed daily and no sooner did an article or statement go viral, like an American ‘doctor’s’ exhortations on YouTube that we soak our tomatoes in bleach, than it was debunked. It’s within this context that I found myself clicking through dozens of high resolution files of Tatiana Trouvé’s most recent drawings while we chatted on Whereby.

Trouvé’s approach to each individual drawing unfolds according to an intuitive logic.

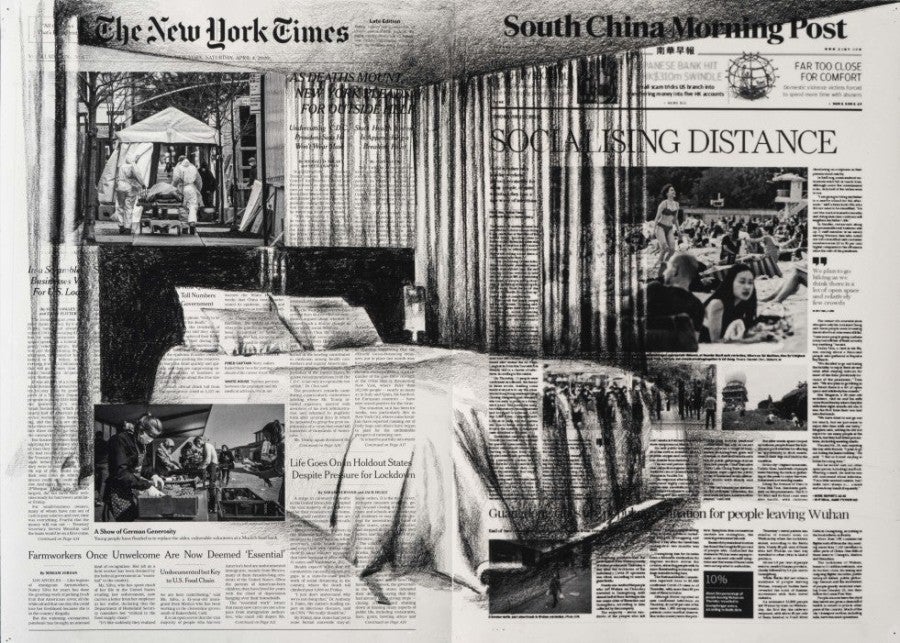

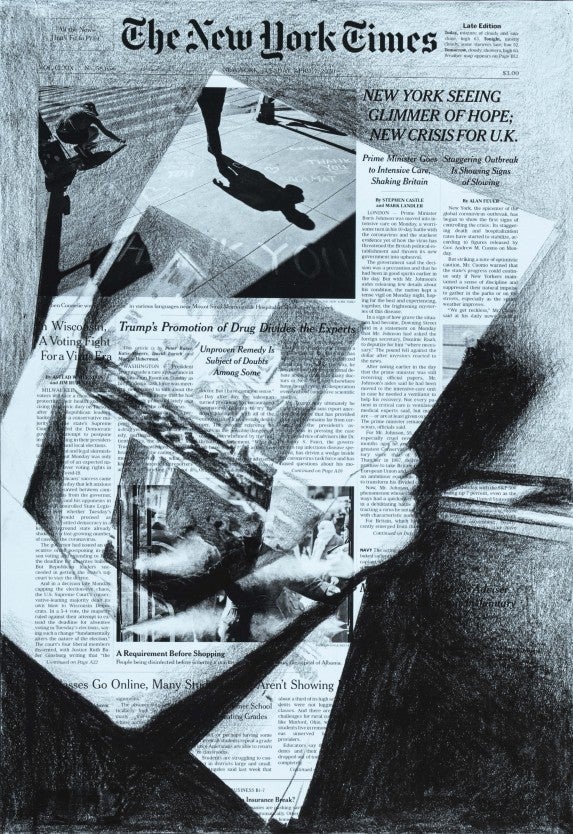

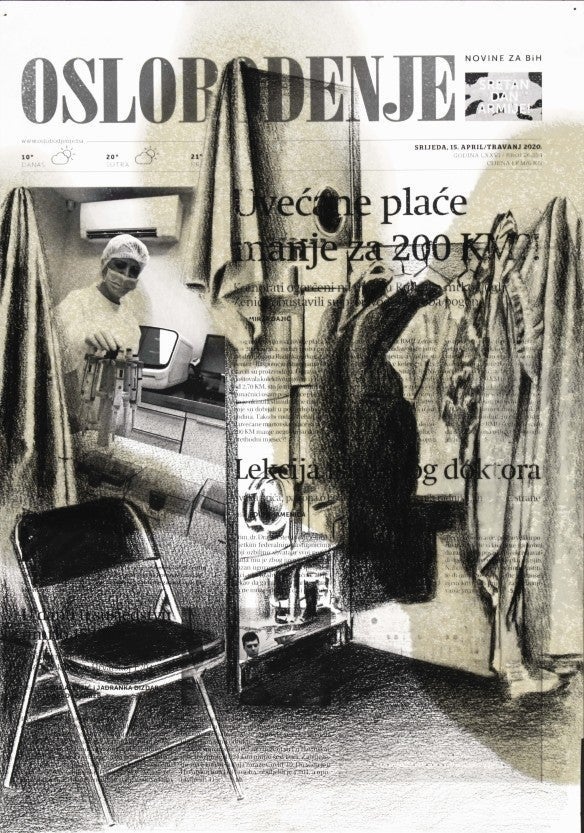

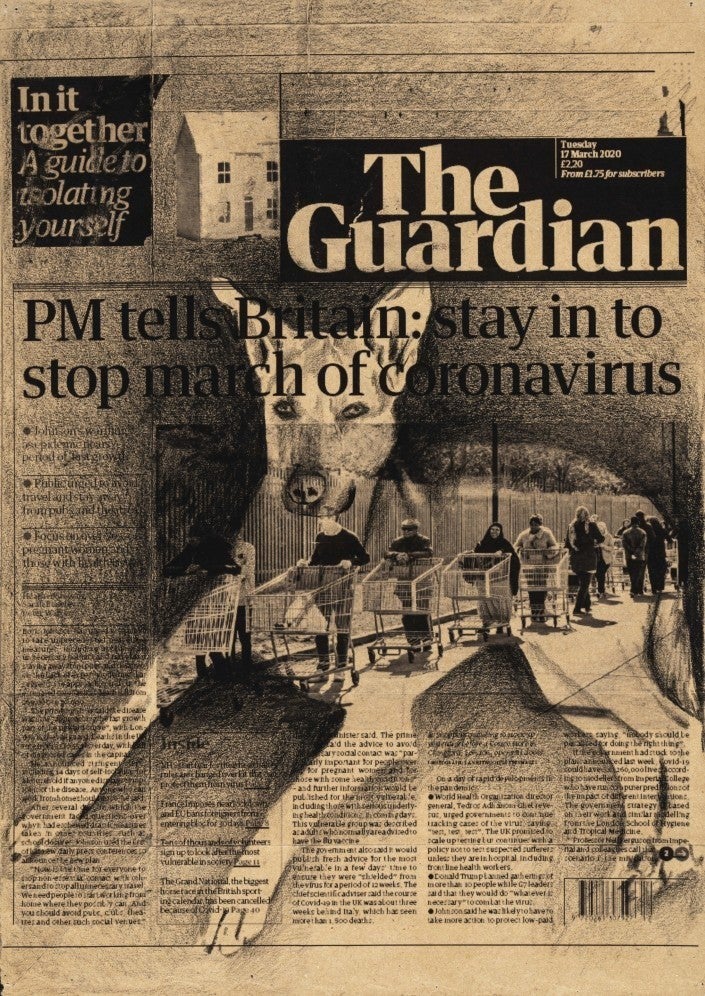

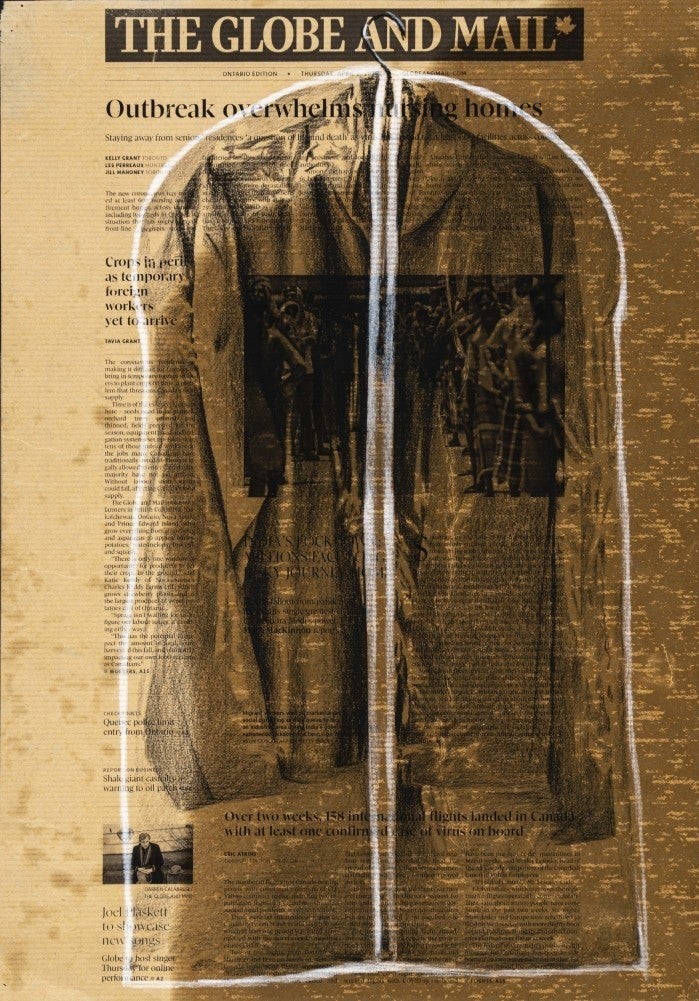

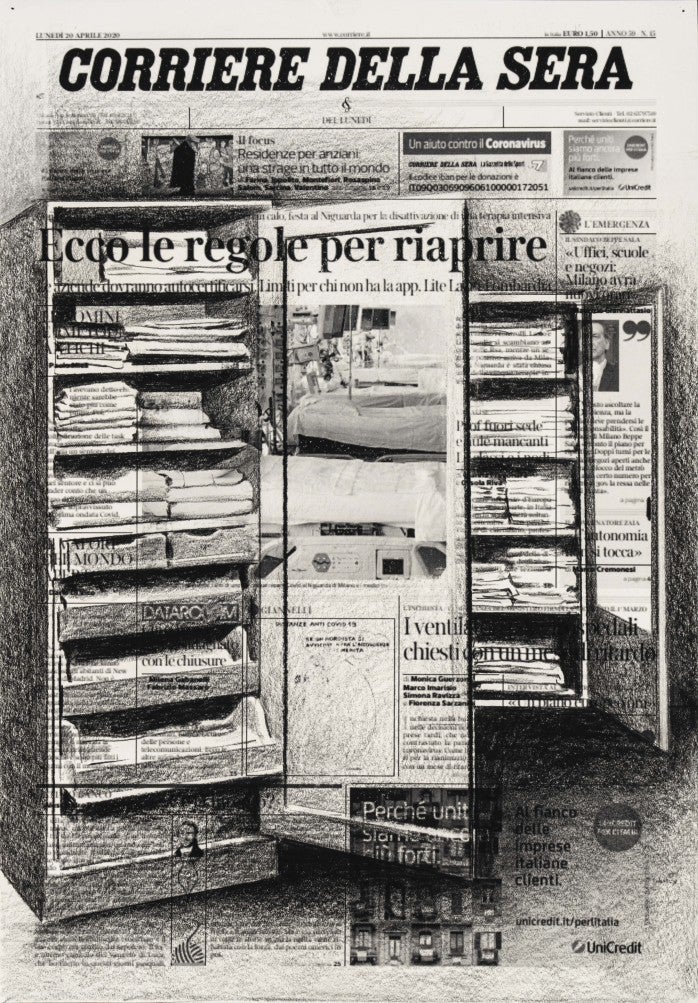

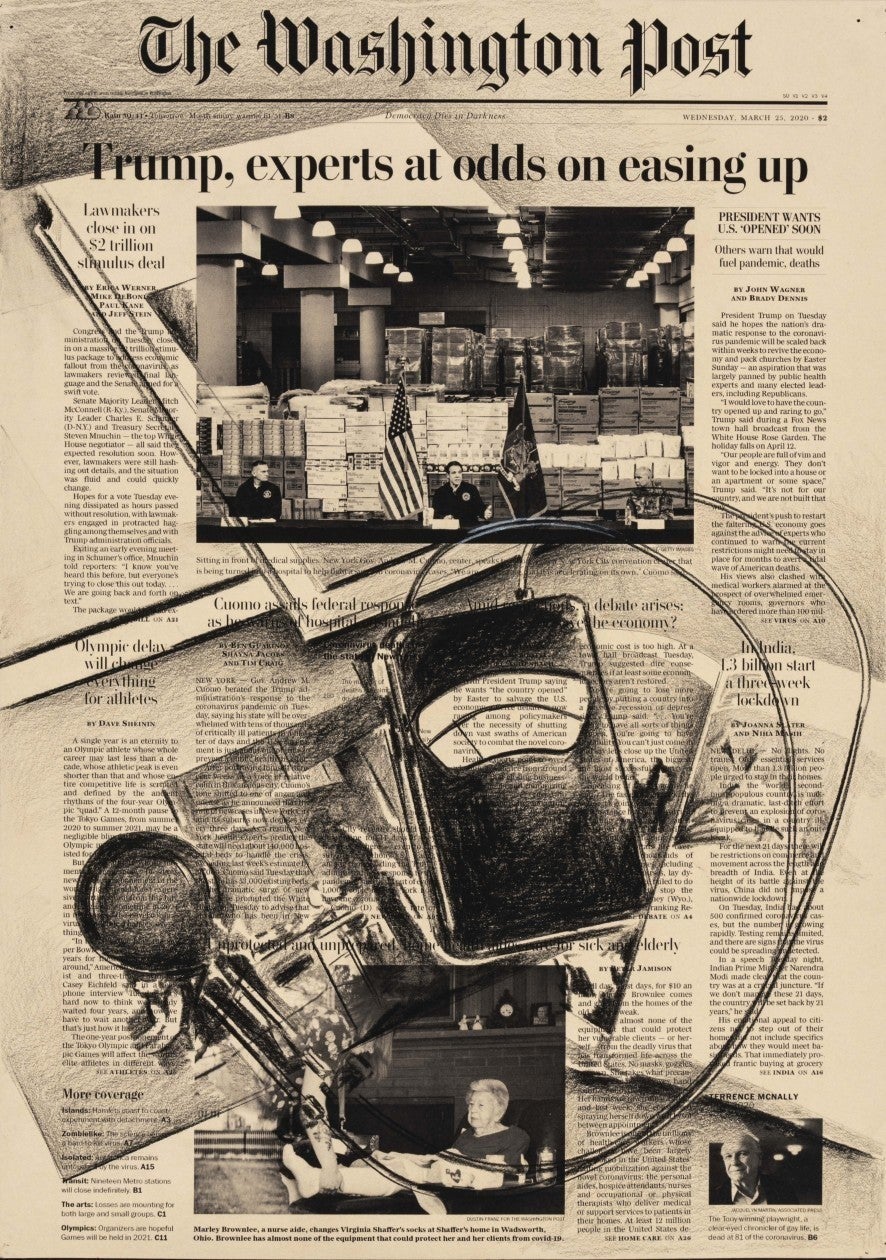

While in confinement at her home in Montreuil, Trouvé created forty drawings atop the front pages of international newspapers from countries severely affected by the pandemic. She started the practice of making a drawing a day the day before the official quarantine began and ended after 40 days, even if the country was still locked down. The first one I opened showed a drawing that extends over the front pages of The New York Times and the South China Morning Post. Each paper strikes a decidedly different tone, with The New York Times reporting on the mounting anxiety leading up to the virus’ peak while the South China Morning Post dealt with questions related to COVID-19’s social impact and how to incorporate social distancing into daily life. Amongst photographs and headlines responding to two very different points on the arc of the virus’ spread, Trouvé had rendered in charcoal a secluded space of repose: an ample bed with a fluffy duvet and floor-to-ceiling drapes. There is something sinister about the comfort and elegance that this minimalist interior offers, particularly in light of the surrounding headlines. In some parts of the composition, her drawing seems to extend into the newspaper’s photographs, creating a quasi-illusionistic space, while in others photographs of hazmat-suited healthcare workers or masked youth preparing care packages create a rupture in the off-putting drawn space of Trouvé’s deserted interior.

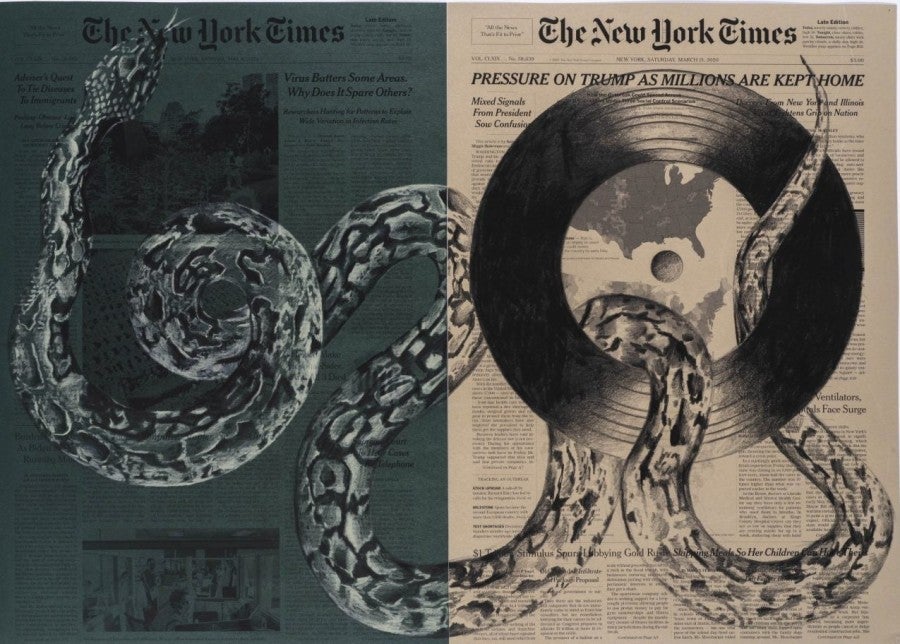

The series has a fleeting, diaristic quality and Trouvé’s approach to each individual drawing unfolds according to an intuitive logic. Some of the works, like an abstract drawing depicting looping coils of black and white tubing that twist and curve around images from The New York Times and Le Soir, seem to respond directly to the paper’s contents, as if to gesture towards how the pandemic foregrounds our mutual biological, environmental, and political entanglement, while others, like a copy of The Guardian from 17 March or La República from 23 April, offer glimpses of Trouvé’s daily life in her studio, shared with her dog Lulu, and the works laying around there.

Trouvé’s own description of the series is relatively straight-forward. Making drawings on international newspapers, she told me, was a way to travel around the world without leaving the confines of her studio. Because she couldn’t buy the physical editions of many of these papers in Paris, she printed out the front pages of digital versions on A3 paper and made the drawings on top of them. This gesture, of course, relates to a long lineage of artists working with the news, projects that range from being staunchly political in scope like Robert Morris’ 1962 protest of Cold War politics in his Crisis (Act of War: Cuba), which submerges the front page of the New York Mirror in grey paint, to more abstract ones like Lorraine O’Grady’s enigmatic 1977 poem sourced from a year’s worth of headlines from the Sunday New York Times or Laurie Anderson’s newsprint weaving of editions of The New York Times and China Times in 1971-79. Trouvé’s recent engagement with newspapers highlights the temporality of the print format as well as its endangerment—threatened not only by the decline of print media, but also the proliferation of fake news within a “post-truth” era. With the accelerated rate of how information circulates and morphs, particularly when following the trail of an international pandemic, a printed newspaper today may risk being outdated before it even hits the newsstands. These recent drawings, therefore, form a kind of time capsule that merges the official version of a public narrative at a fixed moment in time with private, hermetic reflections drawn during roughly the same time span—resulting in a dream-like, at times nightmarish space, where different times and places coexist and are superimposed.

Myriad passages could be sketched through the three decades of Tatiana Trouvé’s practice and the thematically, aesthetically, and conceptually intertwined projects that these years have produced. Yet perhaps it’s worthwhile to linger here on the notion of passage itself, a term that I have chosen quite deliberately in relation to her work because of the unique triangulation of action, space, and affect it implies. Passage connotes an architectural element that connects two distinct spaces, as well as “the action or process of passing from one place, condition, or stage to another.”1 It also refers to rites of passage—formative events that mark the movement from one state of being to another—and the passage of time: its different registers, how we spend it, how it moves quickly or not at all, its materiality, its absence, its dynamic, elusive quality, its preciousness. Trouvé understands her sculptures as “travelers crossing space and time,”2 and indeed throughout the arc of her thirty-year career, we see a preoccupation, as I will explain in this text, with questions related to drifting, wandering, and mapping—but also their associated mental states, which articulate ways of being in the world. I will argue that this drifting, these passages that her work proposes, are not merely forms of travel and circulation, but also denote the movement between interior, mental spaces and the world beyond its bounds. In tracing these movements, Trouvé articulates a new form of space: a space of becoming, a space of latency, a space of possibility.

2.

Born in Cosenza, Italy to an Italian mother and a French father, Trouvé spent her early childhood in Italy and adolescence in Senegal, where her father taught architecture in Dakar. After studying at Villa Arson in Nice, she spent two years in residence at Atelier 63 in the Netherlands and settled in Paris in 1995. Trouvé was awarded the Prix Ricard in 2001 and participated in the Venice Biennale in 2003. A solo exhibition at Palais de Tokyo in 2007 was followed by a site-specific installation for Robert Storr’s Think with the Senses—Feel with the Mind at the Venice Biennale that same year. 2007 also brought the prestigious Marcel Duchamp Prize, which resulted in the solo exhibition 4 between 2 and 3 at the Centre Pompidou the following year.

[Bureau of Implicit Activities], which can be considered the fundament of Trouvé’s engagement with questions of time and the archive, examines the creative process in its most expanded sense...

In 1997, Trouvé began working on her breakout work Bureau d’Activités Implicites [Bureau of Implicit Activities] (1997-2003), a series of thirteen archival, architectural ‘modules’ that chronicled her early days as an artist. She once described Bureau of Implicit Activities as a kind of brain, “a large-scale portrait of a life.” And indeed, this work, which can be considered the fundament of Trouvé’s engagement with questions of time and the archive, examines the creative process in its most expanded sense—by providing not only a space for her unrealized ideas, but also for past projects that have never seen the light of day and ancillary activities like searching for a job or preparing a grant application. The various modules of Bureau of Implicit Activities emerged from the impulse to give the ‘unproductive’ and seemingly inconsequential moments related to the creative process an architecture and, moreover, a logic. I’ve not had the opportunity to experience the work physically, but when looking at the dimly lit photographic documentation of the work’s presentation at CAPC in Bordeaux in 2003, I can imagine that wandering between these open-plan modules, which have been displayed publicly both as small constellations and in their entirety, imparts the feeling of drifting between different states of attention: there is time for thinking, time for remembering, time for daydreaming, time for waiting.

Each module seems to possess a different aesthetic mood, as if to externalize different facets of an interior world. A simple structure festooned with colorful, vertical felt stripes and large windows forms the series’ Administrative Module (1997-2003), the bottom of which is lined with the artist’s various identity cards, partly documenting her search for a job. There is something slightly ramshackle, yet festive about this construction when compared to other modules. A glimpse inside one of its windows reveals plastic-sheathed strips of paper sampled from numerous rejection letters from job and grant applications while passport-sized portraits of the artist are organized within a grid of thick rubber-bands, defaced by the addition of small metal grommets or scratches.

The curved, reflective walls of the Reminiscence Module contain an archive of sealed-off memories written on tiny slips of paper, while the archive module Secrets and Lies from 2003 resembles an ominous workshop or dystopian industrial kitchen. Black metal shelving units and water coolers flank a double-tub sink structure and shiny textured metal floor to create a semi-enclosed space. Long strands of brown twine dangle from small holes in one of the walls and skim the bottom of the exterior wall. On the interior wall, black gridded, open-plan shelves house spools of twine and three small freezer units opposite a shelving unit teeming with small, lumpen objects: secrets and lies that had been whispered into balloons, scrawled on paper, or written on tags before being cast in cement and wrapped in cellophane. My first time hearing about this work immediately sparked vivid mental images. I could clearly imagine the respiration of Trouvé’s words causing the balloon to swell with meaning and intention, only to be deflated by time, to disappear without a trace. Perhaps the lifespan of most secrets and lies are roughly the same as a latex balloon, which takes six months to four years before it biodegrades. Yet the relevance of some last much longer, taking a lifetime or even generations to process or undo. Some of them seem more significant than they really are, while others may seem so ingrained in daily patterns and understandings that they seem inconsequential, or even invisible. Memory and language, like the material of the balloon that this coupling fills, are both elastic after all.

Trouvé’s Bureau of Implicit Activities emerged on the French art scene during the heyday of “relational aesthetics” and a wave of event-based works that created platforms for ephemeral interpersonal exchange. But while the practices associated with Nicolas Bourriaud’s term focused on the dynamics of human relations and their social context, Trouvé’s work at the time took a much more hermetic approach and was more inwardly focused, instead honing in on the dynamics within an individual and the systems she encountered. Bureau of Implicit Activities chronicled a rite of passage, the early days of identifying as an artist, as well as the slippages between different identities that one experiences over the course of a life. An unwieldy archive, it not only served as a receptacle for recovered moments of different aspects of the artist’s life, moments deemed insignificant or inconsequential, but also an extension into other lives in that the Bureau functioned as a kind of narrative machine that allowed Trouvé to experiment with different roles and identities. During this period, most of Trouvé’s installations were on a scale that couldn’t be used. They invited participation, yet from a distance—demanding a form of mental travel similar to what we experience reading novels. The sealed modules of the Bureau of Implicit Activities not only called latent projects and ideas into being, but it gave form to the intangible spaces within a person. The Bureau, in the artist’s own words, is a space “at the heart of which disappearance would not only be tangible, but also produce forms almost in spite of itself, against its own grain. I organize disappearance; I archive this void.”3

3.

Walking in and of itself is not a political act, but the pilgrimage and the march are two forms of movement that show extreme depths of devotion...

“To walk is to lack a place,” writes Michel De Certeau, “it is the indefinite process of being absent and in search of a proper.”4 The pendulum swing between orientation and disorientation that De Certeau described here forms the foundation of a number of works in Trouvé’s oeuvre that relate to walking. For her 2015 work Desire Lines, a commission by New York City’s Public Art Fund, Trouvé undertook an extensive mapping project in which she traced the routes of every official pathway in Central Park, ranging from major thoroughfares to secluded walkways. She transferred the length of these routes into colored cord, each of which was then wrapped around a large wooden spool. During the course of the exhibition, pedestrians passing by Doris C. Freedman plaza in uptown New York were confronted by three large racks housing the 212 colorful spools, which resembled outsized sewing bobbins. Each bore two small brass plaques, one with the name of the path whose length the spool contains and another with a historic march, song, artwork, or piece of writing that Trouvé had associated with that route, ranging from the activism of the American civil rights and suffragette movements to the writings of Guy Debord and Baudelaire or the music of Frank Zappa. The work derives its title from the only paths that Trouvé had actually left unmapped: the desire lines, unofficial routes ground by foot traffic that take shape in spite of planned trails or paved pathways. Enrapturing and infuriating landscape architects and urban planners in equal part, desire lines often “record collective disobedience,” as Robert Moor observes, charting a refusal to follow a path as planned.5 Frédéric Gros refers to walking as “life scoured bare” and, indeed when one commits to walking for pleasure they embrace a form of slowness that allows them to merge, albeit momentarily, with their surroundings.6 Gros goes as far as to claim that walking offers an escape from identity and history, and in a way it does, as a meditative act—a space where one can get lost in their thoughts, dream, and drift. Yet walking also has a social dimension that is inextricable from questions of identity and history, particularly when we consider its political and religious significance. Walking in and of itself is not a political act, but the pilgrimage and the march are two forms of movement that show extreme depths of devotion and commitment to a cause, whether spiritual or political—and both of these forms of collective walking are means of claiming public space through the movement of the body.

As an operation deeply linked to thinking and cognition, walking appears again and again in Tatiana Trouvé’s work. A historical line could be drawn from the research of radical pedagogue Fernand Deligny and his notion of movement as a coherent system of self-expression in children deemed hors parole (outside of language) through the psycho-geographic dérives of the Situationists and to Trouvé’s own engagement with roaming. In her series Wander Lines, metal rods trace irregular lines in three dimensions. Routes and pathways that the artist associates with dates and places are inlaid in the rods, giving tangible form to past wanderings. In a related work, Les Indéfinis (2018), metal rods form a kind of zig-zag enclosure for a slim plexi-glass crate. Bronze casts of stones wrapped in twine and a precariously balanced radio provide counterweights for this seemingly unstable composition. Two high heels and a gentleman’s dress shoe flank the bottom of the structure, while one shoe perches atop the crate with its laces dangling. Shoes also appear repeatedly in Trouvé’s work, suggesting human presence, but in the absence of their owner they have a slightly macabre air like a single shoe found on a dusty path or the side of the road. Such objects found out of context generate countless questions and possible narratives. Where did the owner of said shoe disappear to? How are they making do with only one shoe? Were they harmed?

As a metaphor, the expression “walking in another person’s shoes” has long been raised to elicit empathy and understanding for the other—as if retracing someone’s path you could come to understand them. Although trite, such a metaphor, and the notion of re-walking or re-doing a path, opens up an interstitial communicative space that brings together myriad affects, sensibilities, temporalities, and affinities. Movement and its relation to sense-memory thus gives rise to meaning and form. “For me, walking is really a construction of a space,” Trouvé explains, “so is drawing, as it also delimits a space. It’s the first thing you do to make a map.”7 Walking is a productive force—a form of being that opens you fully to your surroundings. To roam is to be between two points, the sky and the earth—suspended between two worlds. Trouvé gives fleeting form to this absence, unfolding, like the walk itself, as a space of enunciation—a long poem full of shadows and ambiguities.8

4.

The body is always absent in these assemblages, as if someone has suddenly hauled off and left the scene, yet the objects they leave behind consistently reference the body and its needs...

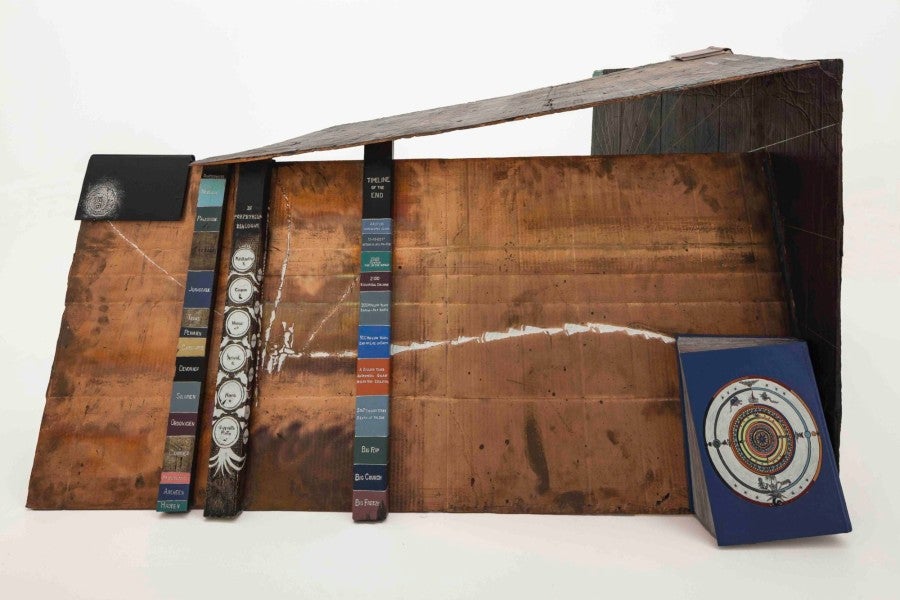

Trouvé’s work with mapping reclaims disorientation as a generative space, and as such, parallels can be drawn to Rebecca Solnit’s description of losing oneself as a form of “voluptuous surrender”9—a state of immersion and presence so intense that one’s surroundings seem to fade away. Upon first glance, the rudimentary constructions of Tatiana Trouvé’s Great Atlas of Disorientation (2018) appear to be comprised of cardboard and thin planks of wood that lean together to form a rough-hewn shelter. The humble aesthetic of these makeshift constructions are accented with additions like geological timelines, phylogenetic trees, celestial maps, and migration routes. Hardcover books adorned with mandala-like paintings are draped over the tops of walls or leaned against them, slightly deformed as if the volumes were bent by the pressure of other objects that they encountered over the course of traveling. However, nothing is quite what it seems. The cardboard, a humble and ubiquitous material with a wide application of uses, turns out to be metal, and the books are not found objects adorned by the artist’s hand, but rather intentionally fabricated artifacts that merely look as if they are special relics from another time. Even questions of scale play tricks on you: the blankets and plastic bags that have appeared numerous times in other works by Trouvé, appear here in an almost comically miniature form, attached to the sides of the walls like tiny talismans. These structures form a kind of relational-architecture that tells stories through traces left by human agents. The body is always absent in these assemblages, as if someone has suddenly hauled off and left the scene, yet the objects they leave behind consistently reference the body and its needs; for care, for shelter, for warmth, or protection. Trouvé’s huts shift between different registers of space and time, collapsing history and linear time into a decrepit structure vulnerable to the elements, yet nonetheless capable of providing a radical form of care and protection. Despite their designation as a form of atlas—something typically associated with order, clarity, and direction—these works elicit a sense of spatial and temporal confusion. What exactly are we seeing here? Is this a structure from the end times or the roots of civilization—a ruin or an accomplishment?

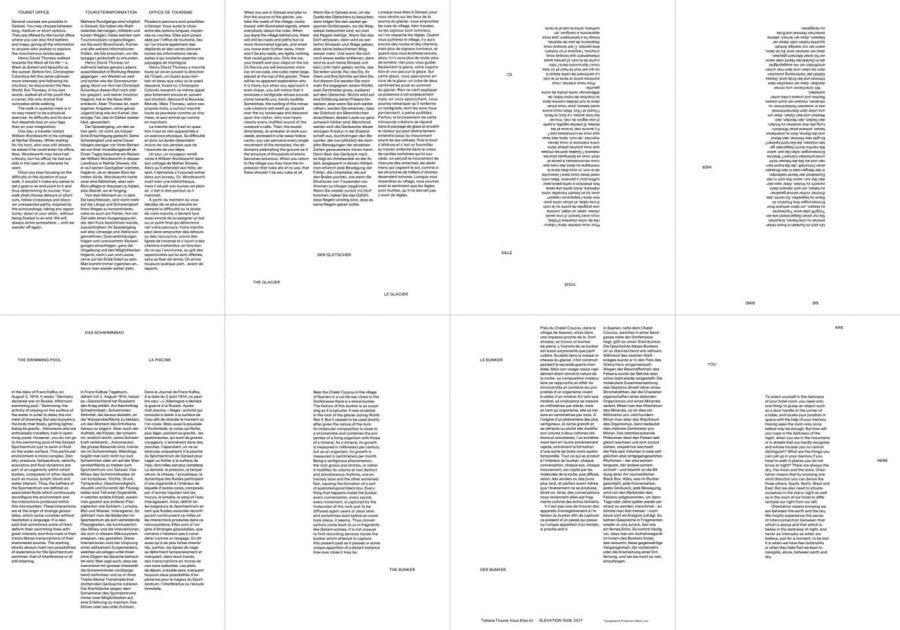

There is a spectral porosity in the scenes that Trouvé’s works create, almost as if they propose a kind of portal where you can be in two places, or moreover, spaces at once. It’s a sort of inverse universe. You Are Here (2017), a site-specific project for Gstaad, Switzerland takes the form of five disorienting experiences installed throughout the town that can be accessed via a fictitious map. At one of the locations, a swimming pool, Trouvé undertook a collaboration with the sound artist Grace Hall, whose composition Obsidian Cloud plays underwater. The motif of the pool reappears in an installation entitled The Shaman, for the exhibition On The Eve of Never Leaving at Gagosian’s Beverly Hills location in November 2019, in which a liquid dimension serves as a gateway to another world. Water pools in a gaping depression within a cracked concrete floor while a bronze cast of an uprooted tree rests in the water, with droplets trickling from its roots. Next to the tree, a sawhorse laden with pillows and blankets rests upon another smaller pillow on a partially submerged concrete slab. Gnarled tree roots rest tenderly atop pillows and a large key ring bearing dozens of keys hangs on the side of the sawhorse as if they could unlock any number of alternative realities. Two works from Trouvé’s ongoing series The Guardian survey the scene from opposite sides of the room.10 These particular iterations of the series presented in On the Eve of Never Leaving bear witness to a blurring of the boundaries of the “natural” world and the built environment via an encounter that seems to have resulted from a mysterious disaster, testifying to a recent, developing interest in Trouvé’s practice in cross-species entanglements and the heterogeneity of space and time that such assemblages produce.

A shaman is a figure who passes between realms, uniting the terrestrial with the spirit realms; human, animal, and plant life; and different spatial and temporal dimensions. The focus on altered states of consciousness in most discussions of shamanism often misses the collective imperative of the shaman’s quest. The state of radical interiority that shamanic journeying requires is generally in the service of a common good. Hunter-gatherer shamanism, for example, was predicated on a wide range of what scholar David Lewis-Williams calls “institutionalized states of consciousness.”11 Through their access to alternative realities and convening with invisible forces, shamans would track the movement of animals, intervene in group conflicts, and chart migration paths for the community. The importance that the co-evolution of plant, animal, and mineral life has taken in Trouvé’s recent works has developed in tandem with an increased attention towards examining forms of mapping that fall outside of the bounds of “traditional” cartography, which has historically been complicit in colonialism and the consolidation of Euro-centric power relations. Perhaps the roots of Trouvé’s interest in mapping—as well as the passages between different dimensions—can be drawn, in part, from her life experience. Growing up in Senegal, Trouvé encountered stories of the supernatural djinn. Part of the Koranic notion of the al-ghaib—which refers to the invisible, the unknowable, and the unseen—these shape-shifting spirits are neither good, nor evil. According to the Koran, djinn were created by god alongside the angels and the humans, and many people believe that they co-exist among us, they are simply made of a different material. Much has been written about Trouvé’s interest in the djinn as they relate to the dreamlike, often chilling atmosphere of some of her earlier sculptures and installations. Yet I see the djinn, to which Trouvé devoted an artist book in 2007, as related to the broader questions of passage that her work tackles, particularly as it pertains to her interest in forms of mapping that derive from collaborative systems of relation—whether aboriginal dream maps, the movement patterns of children explored by Fernand Deligny, or the mental maps of the oral historian griot that Trouvé encountered during her youth in Senegal. In On the Eve of Never Leaving, Trouvé’s Guardian sculptures gesture towards travel to other realms with their transistor radios, bags, pillows, blankets, and shoes—yet they also serve as protectors of a complex form of intelligence. The passages between realms that The Shaman and The Guardian stage seem to insist upon a mutual accountability, a life in common.

5.

One day the gentlemen in grey appeared from another dimension, well dressed and ashen-faced. Although they said very little, they were nonetheless tremendously persuasive. Time, something that previously was expended freely, thereafter became something to be hoarded and saved. Gone were the languid days spent tending the garden or conversing with a neighbor, replaced instead by the ethos of “saving time.” And the gentlemen in grey were there to help. They stored time for the people, compressing it into desiccated, compacted lotus blossoms. And at the end of the day, after their work was done, the gentlemen rolled up these dried flowers into thick cigars. Then they put on their dark glasses and began to smoke.

German novelist Michael Ende wrote about the gentlemen in grey—time thieves who number among the twentieth century’s most chilling and subtle literary villains—in his 1973 novel Momo. Despite their elegance, there is something ordinary about these men who traffic in other people’s time. They are not villains with exceptional super-powers, but more like ingenious bureaucrats who have developed elaborate systems to extract, materialize, process, store, and imbibe time. Although ostensibly a story written for children, a seething critique of the post-war German efficiency culture can be read between its lines.

What might Tatiana Trouvé’s work have in common with such a story? Like the gentleman in grey, Trouvé is a collector of time(s) and she also creates elaborate storehouses of its residue. Yet her activities as a collector of times runs counter to the self-optimization preached by the gentlemen in grey. Instead, she creates architectures and scenarios that channel reflective moments, the time spent wandering, or the passages between realms. “Time has to be thought of in terms of its imperceptible movements, either because they are too fast for us to gain a clear image of them, or because they are too slow for us to discern their movement,” Trouvé explains, “If the time in which I am interested produces neither a clear image nor a perceptible movement, it also leaves few traces and does not appear in any historical register. It does, nonetheless, have the capacity to unite what was, bringing about movements like those of an echo.”12

6.

...tracing the different passages through Tatiana Trouvé’s work during a time when my own movement was so limited enabled another kind of movement and connection, one attuned to interiority, possibility, and dreams...

It seems fitting that my second encounter with Tatiana Trouvé took place during a moment when time seemed to stand still. On one hand this state of exception seemed completely ordinary—as a writer, I’m no stranger to extended periods of time at home working. Yet confinement nonetheless drastically altered my conception of time, space, and crisis in other ways. For those like myself—meaning those fortunate enough to not fall ill, lose their income, or drown under the weight of balancing unpaid care work with securing their livelihood—the COVID-19 quarantine could best be described as a collective mind fuck that fundamentally, albeit temporarily, changed our perspectives regarding the limits of our bodies and, particularly, about the safety of objects and interstitial spaces. Passages between private and public space suddenly seemed fraught with potential danger. Media reports repeatedly stressed how long the novel coronavirus was capable of living on surfaces and these estimations varied daily. Inanimate surfaces seemed to teem with life—and the perceived possibility to bring us harm. The doorknob, the cereal box at the grocery store, the pole on the bus, anything once handled without a second thought became a repository of touch, a storehouse of contagion. What was so disorienting about this time was how we shared different registers of a similar experience of confinement simultaneously around the globe. Yet tracing the different passages through Tatiana Trouvé’s work during a time when my own movement was so limited enabled another kind of movement and connection, one attuned to interiority, possibility, and dreams—drifting, between enclosure and space.

Tatiana Trouvé, “Complex Forms of Intelligence: A Conversation with Tatiana Trouvé,” Sculpture Magazine, October 30, 2019: https://sculpturemagazine.art/complex-forms-of-intelligence-a-conversation-with-tatiana-trouve/ (last accessed July 23, 2020).

Tatiana Trouvé and Richard Shusterman, “Body Without a Face: A Conversation with Tatiana Trouvé and Richard Shusterman, in Tatiana Trouvé (Cologne: Buchhandlung Walter König Verlag, 2008), p.121.

Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1984).

Robert Moor, “Tracing (and Erasing) New York’s Lines of Desire,” New Yorker, 20 February 2017: https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/tracing-and-erasing-new-yorks-lines-of-desire (last accessed 15 July 2020).

Frédéric Gros, A Philosophy of Walking (New York: Verso, 2014).

Interview with the author, May 2020.

See Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life. “The long poem of walking manipulates spatial organizations, no matter how panoptic they may be: it is neither foreign to them (it can take place only within them) nor in conformity with them (it does not receive its identity from them). It creates shadows and ambiguities within them. It inserts its multitudinous references and citations into them (social models, cultural mores, personal factors). Within them it is itself the effect of successive encounters and occasions that constantly alter it and make it the other's blazon: in other words, it is like a peddler carrying something surprising, transverse or attractive compared with the usual choice. These diverse aspects provide the basis of a rhetoric. They can even be said to define it.”

Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost (New York: Penguin, 2006).

The series of sculptures entitled The Guardian were inspired by the folding chairs often used by guards in museums, and Trouvé’s own experience of working as a guard at Centre Pompidou when she first arrived in France. These anthropomorphic works give a sense of the person who might sit in such a chair through the objects they leave behind, marking presence through absence, but also engaging questions of care. “I wanted to make a sculpture that takes care and is dedicated to other sculptures,” Trouvé explained to me during our conversation in May 2020.

David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002).

Tatiana Trouvé, "The Longest Echo” exhibition catalogue, 2014.