In the Body, in the Room, in Space

When I was invited to write this essay on Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, I thought: I could begin anywhere. In the body, in the bedroom, in outer space. I could begin outside the locked door of a hotel room. I could be on the beach or on another planet, waiting in a port or performing onstage. Perhaps I should begin in a tidy, green European park, encountering a series of strange large incongruous objects: a lump of volcanic rock; a slender modernist bench; a lamp post. Or I could begin in a dislocated exhibition space, walking on a polished concrete pathway through a white hangar which is gradually filling with the complicated, intense sounds of a tropical rainstorm. I could go back to the past, meeting a flickering vision of Marilyn Monroe as she dances alone in a darkened space. I could cut forward to the future, lying on a metal bed-frame inside a bunker in a disused power-station, surrounded by reproductions of famous sculptures that have been strangely swollen by apocalyptic rain. I could begin inside my own body, listening, tasting, smelling, blinking: a room infiltrated by a musky scent; a gallery flooded with the sound of a recorded aria; a pattern of moving lights that respond when I move. I could begin at the greatest distance imaginable from myself, disembodied, floating in a virtual reality that is suspended in deep space.

Gonzalez-Foerster is an unusual artist: it’s hard to find the work that can act as synecdoche because it’s all so different. People who visit her shows, or look across her career as an artist – from the first solo exhibition in the library of the art school of Grenoble in 1986, to the current intervention at Serpentine Galleries, London – have noticed a tendency towards everything. Her titles suggest sweeping spaces and long timelines: chronotypes & dioramas; Endodrome; Exotourisme; Solarium; Temporama; Cosmodrome. Gonzalez-Foerster was born in Strasbourg in 1965, but the span of her life’s work is summarized more accurately in the title of her 2015 Pompidou Centre retrospective, addressing as it does the timeframe of the works, 1887-2058. She crosses continents, living between Paris and Rio de Janeiro. She mixes media, making projections and music, objects and performances, sculptures and scripts. Her works include an opera, and a personal appearance in the guise of Bob Dylan. A long film without action or narrative, that floats through urban spaces, and a brief narrative film in which a woman awaits the ferry that will take her away. A dressing-up room, and a script for a manga character. Museum dioramas from the deep future: abandoned books in a synthetic landscape. A succession of stories about the artist’s experiences of producing work for the Venice Biennale over several different years. A secret garden. An invitation to dance.

What interested me most, when I was invited to think and write about her work, was the movement itself – the way this far-reaching range suggests an expedition or an exploration, a mission, tourism. I started at the edge of the universe and crossed scales, through a sequence of the contained spaces that Gonzalez-Foerster has created, then down into the body.

World

...she’s careful about the terms she uses to describe what she does...

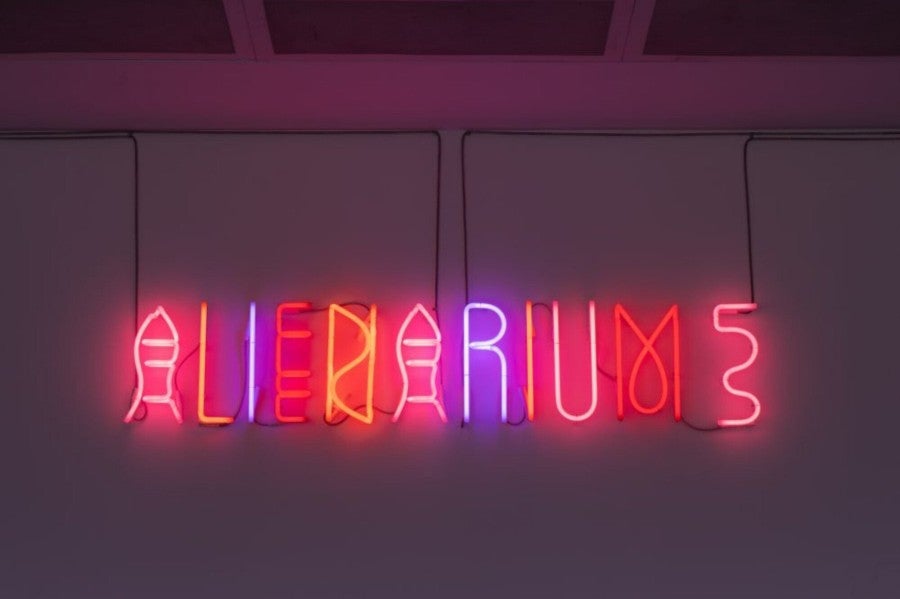

Gonzalez-Foerster’s current show in London is bigger than the universe. Inside Alienarium 5, deep space is a starting point: the show swiftly moves outward from here, entering alternative dimensions and encountering spirits. It extends into digital landscapes. It meets nonhumans, extra-terrestrials, and ghosts. It travels to the past and the future. There’s a collaged panorama, a curated library, a secret room, video works, radio transmissions, sculpture, and a VR journey which moves beyond earth’s solar system.

When I spoke with Gonzalez-Foerster during the period that she was preparing this show, she was completely zoned in on it. She wasn’t much interested in talking about past work, and she was relaxed about reception: her mind was on the present, on what she was making next, and what she was making was an entirely new experience – an experiment. ‘I’m a person of first times, I’m not good with repeating or rehearsing.’1 She doesn’t have a studio because she prefers to spend her days out in the world: ‘I like to wake up and then watch a film and sing and walk. In that sense, there is always a risk. I don’t do what I know how to do, rather the opposite: I try to experiment.’

We were speaking over Zoom that day, Dominique was speaking in English for my sake. She’s used to translation – she’s careful about the terms she uses to describe what she does, and thinks about how each word could resonate in different languages. She needs a vocabulary that has precision while allowing for complexity: ‘apparitions’ rather than performances; ‘experiences’ rather than installations. I remembered how, in French class at school, I was told that the word expérience was a false friend – translating in English not only to ‘experience’, but also to ‘experiment’ – but the word’s double exposure makes good sense, in this context: Gonzalez-Foerster’s experiments are unified by their emphasis on experience. She describes her work as experiences, not objects. ‘An opportunity to feel and to be something new.’

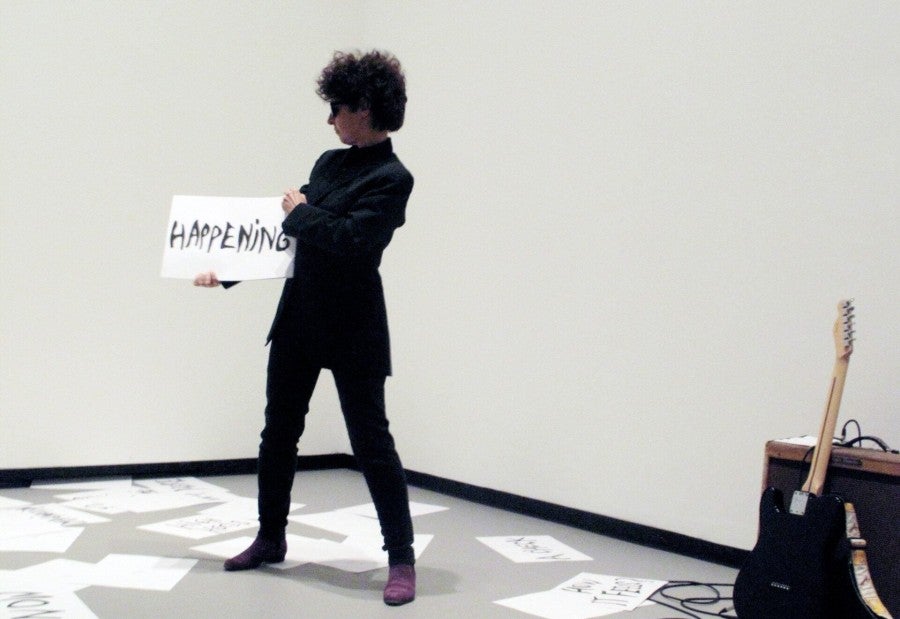

The image glitched at my end. When Dominique held up an open book for me to see, the computer automatically blurred out the image. At times, she used the language of an animate portal or interface to articulate what she engineers: the individual pieces are ‘exhibition devices’ – technologies that grant access to particular experiences. Alienarium 5, the experiment she was undertaking as we spoke, was a universe that brought together old and new technologies – virtual reality, architectural design, books – each of which can facilitate an encounter across difference. These devices and displays are experiments, but they don’t come from out of nothing. There’s an ongoing series of works that she calls her apparitions (2007- ) – the word denotes an appearance, something coming into view, but it also implies something spookier. Gonzalez-Foerster prepares for these works for months, reading and researching a particular historical or fictional figure: the protagonist of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, or Scarlett O’Hara, or Edgar Allen Poe. After that, only in the moment of the apparition, Gonzalez-Foerster herself enters into this character. She takes on their clothing and movement, using make-up and music, and something else – something that isn’t available to verbal description – to transform her being into theirs. Later, in an email, she described the experience to me as a ‘trance / almost a kind of medium experience’.

The apparitions take many forms. Gonzalez-Foerster is Vivien Leigh’s O’Hara in Kyoto, a replicant from Blade Runner in Paris, King Ludwig II in New York. These different personae come into play with one another within larger projects: for Teatro (QM.15), which first appeared at the Esther Schipper gallery in Berlin in 2016, Gonzalez-Foerster transforms herself into projections of female performers: Sarah Bernhardt, Marilyn Monroe, and Maria Callas. They’re separate, but connected in that each woman was exacting if not punishing in her dedication to the performance of herself. M.2062, a fragmentary opera, was initiated during the Serpentine Gallery’s ‘Memory Marathon’ in 2012, and developed during the following years across multiple apparitions around the world: Dublin, St Petersburg, Kyoto, Gwangju, Berlin, Paris. Its apparitions are almost bewilderingly diverse, Vera Nabokov and Bob Dylan; dancer and courtesan Lola Montez, and fictional colonial Fitzcarraldo.

I watched videos of one work after another – a rapid relay of apparitions, switching costume, scenography, music, and persona, from one moment the next – it would be logistically impossible in real life. Seeing them in close succession, I noticed that many of the apparitions draw attention to their own staginess: the props and the velvet curtains, full lighting systems and overwhelming soundtracks. There are sequins and glitter, there is neon face-paint. But the character at the centre of all these staged events appeared to me, perhaps counterintuitively, as a person who is unusually composed – I could almost say self-possessed. Gonzalez-Foerster’s being moves, or is moved, with deliberation, whether she is a Blade-Runner replicant onstage at a pop concert or Faye Dunaway in sugar pink, sitting with a chessboard, playing alone.

Her turn to thinking with the alien means thinking about this otherworldliness in a literal, environmental respect...

The apparitions give a sense of the experience that Gonzalez-Foerster proposes: at once trippy and deliberate. It’s compelled towards something magic, entrances to different realities – but it takes work to become something different, another person or being. Gonzalez-Foerster uses technologies, materials, architectures, and settings, and she commits to whatever is required to create these otherworldly experiences. Her turn to thinking with the alien means thinking about this otherworldliness in a literal, environmental respect: alternative planets and their speculative ecologies. But naming the alien also means naming the refugees who are living on this planet, here and now, and it raises questions about nationalism, decoloniality, and border control. The border between self and other is a political border, aligned and held in place by laws and hierarchies that discriminate as they distinguish. And so crossing between one person and another, from native to alien, is always an uneasy process. It takes time. There’s a need to honour this difficulty. The period of learning and working is a requisite for Gonzalez-Foerster to develop each costume and soundscape, each complex environment and each embodiment – to create and then enter another persona’s world.

I wanted to know what the word world means to her. Her work draws attention to it – to these individual lifeworlds; to notions of the universe, of space, of everything and everybody. In response, the first thing she did was laugh – ‘there are many different possible ways to answer that’ – and then she spoke about difference. Everybody is aware that the physical world is shared between many beings, she explained, ‘but we live in so many different worlds in terms of how we relate to that world. To try to engage with this larger dimension, that goes beyond the object or the domestic dimension, maybe that is what the word world calls for’. The universe is always plural, which is always a paradox. I thought of an essay by Jorge Luis Borges, in which he tries to make sense of the idea of the universe, and realises that the scale and complexity of the world exceeds any attempt to think it all up. ‘[T]here is no classification of the universe that is not arbitrary and speculative. The reason is quite simple: we do not know what the universe is […] We must go even further, and suspect that there is no universe in the organic, unifying sense of that ambitious word.’2

For Gonzalez-Foerster, the world is ‘complexity’. The world is always worlds. No universe but the multiverse: it can be a set of connections, relations, ‘something that surrounds, rather than something that is in front of you.’ At the centre of the Serpentine building there is a single circular space that surrounds the viewer. Metapanorama is a collage that brings together another unexpected crowd: here’s JG Ballard and here is Ada Lovelace, not far from Audre Lorde, who is facing Princess Di, and all of these are assembled with a huge image of planet Earth, rising like a blue marble – as you’d see it if you were looking from the moon. There are other, imaginary planets, Saturn’s moons, nebulae, rocks and space rubble. There are dendritic forms that could be close-up views of plant capillaries, or satellite images of river delta. Slime moulds and jellyfish, a Tellytubby. There are representations of famous modern sculptures, Henry Moores and Yayoi Kusamas in perfect miniature. There are corals, plants, explosives, and aliens from movies. It’s all drawn together in the circle – it’s a universe in a room.

Room

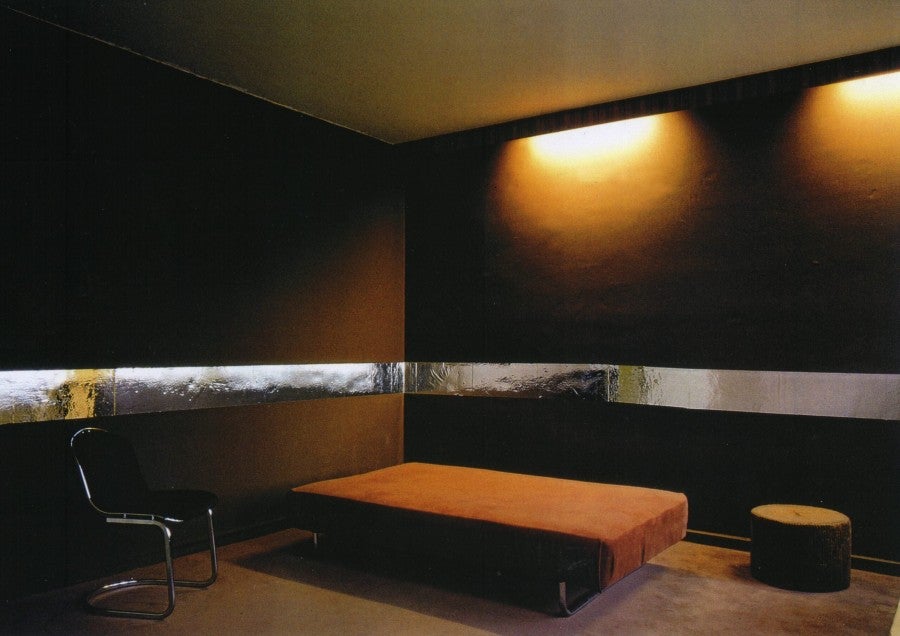

Gonzalez-Foerster is interested in room. Inside her exhibitions, she often places literary works which are concerned with the different ways in which room has been defined or imagined by authors and thinkers – how space is circumscribed, contained and controlled, traversed and inhabited. These references, theories of space, offer possible trails to follow. But Gonzalez-Foerster’s works and shows also make the viewer directly and immediately aware of the contained, unitary space that surrounds them: the room itself is the medium, one which has been described as the artist’s own invention.3 Between 1991 and 1998 she created perhaps sixty rooms/chambres: works that reimagine and reconstruct their exhibition space, so that the space itself is exhibited.4 Painted walls or partitions, carpeted areas, hangings and curtains, are used to make a room draw in around the viewer, creating a feeling of being environed. Many of these rooms are familiar in their anonymity. Gallery spaces are annexed and repurposed to become liminal zones: corridors and atriums, dressing rooms or waiting rooms. These clinical, quiet spaces, with their potted plants, closed doors, and expanses of hoovered carpet, are open to different directions. Other rooms feel deeply personal– studies and bedrooms – but these are also furnished minimally, painted in quiet colours and populated with carefully selected objects and furniture. A pair of small chairs or a narrow bed. An inkjet printer. An open paper parasol. Pictures on the wall of nocturnal landscapes; of alternative interiors. A book on a bedside table. Each room has its own distinct atmosphere, as vacated habitats often do. The atmosphere exerts pressure: it can act interiorly. The room becomes a means of access to another experience. Each one’s a wormhole.

Gonzalez-Foerster has described her apparitions – the process of becoming, or manifesting, another character through her own body – as an attempt to push at the edge of what an artwork can do: ‘an attempt to get inside the work and be the work’5. This could also be a description of what happens to a person who enters one of her spaces – a room, or one of her wider, weirder environments. The installation that drops you into a tropical rainstorm. The park that places you in a compact desert of white sand and smooth concrete. The film projection that could be a nightclub. When you cross the threshold, you’re contained by it. A desert or a bedroom, a dancefloor or a rainforest: they receive a viewer or audience-member as a tenant or inhabitant. You can enter as a gallery visitor, speculating on who might populate this novel environment. But then you’re in there, and the population is you.

These works have been developed by Gonzalez-Foerster across several decades and are still developing. During this period of history they have been unfolding within, and in synchrony with, an evolving understanding of planet and power. Europe’s story of modernity has been the story of the human – a white, gendered individual who defines himself in opposition to his environment: to minerals, plants, and animals, but also to the enslaved, stateless, or queer, or otherwise alienated bodies whose historical exploitation has been premised on their not being fully humanised. Over the years, through Gonzalez-Foerster’s career as it continues in the present, this story has reached a point of crisis. Assumptions of hierarchy and agency, of actor and background, are collapsing, and alternative stories, in which the nonhuman has always been respected and granted agency, are coming to the fore. Textbau (2018) includes a series of wall-texts that directly challenge human exceptionalism and the elevation of human work. ‘Why is it more important to think about art than take care of plants or living things […] in what way is art adding something to biodiversity or rather threatening it?’

...we consume and extract even as we comment on the crisis of consumption and extraction.

Gonzalez-Foerster places a finger, here, on the tender point of an art-world in-joke: we consume and extract even as we comment on the crisis of consumption and extraction. It’s ‘like destroying a forest to build an opera in which a forest might appear on stage.’6 Her leafy imaginary stage reminded me of an image from a piece of writing by Bruno Latour which seems to be rooted in the same earth. Latour describes changes in the concept of the universe. This is a new expansion, he says. It doesn’t extend out into deep space, the zone where the aliens live. Instead, it estranges the familiar, venturing into the immediate surroundings:

What is called civilization, let us say the habits acquired over the last ten millennia, has come about, the geologists explain, in an epoch and on a geographic space that have been relatively stable. The Holocene (this is what they call it) had all the features of a “framework” within which one could in fact fairly readily distinguish human actions, just as at the theatre one can forget the building and the wings to concentrate on the plot.

This is no longer the case in the Anthropocene, the disputed label that some experts want to give the current epoch. Here, we are no longer dealing with small fluctuations in the climate, but rather with an upheaval that is mobilizing the earth system itself.

Today, the decor, the wings, the background, the whole building have come on stage and are competing with the actors for the principal role. This changes all the scripts, suggests other endings.7

The image Latour uses, of a theatre whose wings, stage and scenery have picked themselves up and started to move, is somehow brought to life in Gonzalez-Foerster’s work. A stage-set isn’t décor. A corridor is not just a means to an end. Her spaces are not features of a background – contexts, settings, backdrops, buildings, empty room – they are atmospheres and environments that act on the body.

Being inside one of these spaces induces an experience of difference – a new ending. Gonzalez-Foerster’s description of art as an environment or envelope (‘something that surrounds, rather than something that is in front of you’) works across boundaries. Increasingly, she presents the bulging or breaking of the borders between contained spaces: content and viewer, inside and outside, host and alien. Alienarium 5 extends out from the Serpentine Gallery into the surrounding environment, and beyond. Works in the exhibition can be viewed from the exterior of the building, one glimpsed only through the small glass panes of the antique French windows. Some of these panels have been blocked out, others left for viewers to peep through. There are a few transparent panes low down on the doors – accessible to a snail or a fox that lives in the park. There are also sonic ‘transmissions’ that can be received from points across Hyde Park. People can tune in on their way to the gallery, or afterwards, as they move on. Outside the gallery, the transmissions of Alienarium 5 come through from outer space; inside the gallery, at the heart of the exhibition, the world crowds onto Metapanorama’s walls.

When we spoke over Zoom, Gonzalez-Foerster located the crowd at the core of her own being. She described to me ‘a shift’ in her own experience which has happened over the previous years. She senses a movement away from her previous explorations of room in ‘waiting and empty openness’ – the atriums and corridors, the suggestive space. In its place, there’s this ‘rush or an invasion of beings’.

Twenty or twenty-five years ago, she said, she might have staged a set for a crowd. She recalled Brasilia Hall (1998-2000), a long plush green carpet inside a white-walled room. A neon orange sign, and a small video screen portraying images Oscar Niemeyer’s buildings in Brasilia. The purity and clean lines of Gonzalez-Foerster’s environment harmonise with Niemeyer’s modernist architecture. These days, Gonzalez-Foerster doesn’t exactly distance herself from this work, but she describes a sense of movement within herself that has brought about this change in the way she relates to space. ‘Years ago – it might sound strange, but I identified with empty spaces, empty rooms. Now I feel more like a part of the bodies, part of the crowd.’ We talked about COVID-19 and ecosystem collapse, and how recent history has repressurised relationships between environment and body. Gonzalez-Foerster also suggested, more tentatively, that, while these external phenomena have affected her, there was also something going on that was particular and internal to her own body. The experience of her apparitions, ‘ways to embody and to enter’, could have influenced the shift in her felt perspective here, the sense of switched experience. The Brazilian climate, with its intense, diverse, flourishing biological processes, is both an image for, and embodiment of, ‘cross-fertilisation’. Crossing between Europe and South America, Gonzalez-Foerster draws attention to the movement itself as a generative process – when she speaks of her experiences living and working in Rio, what she describes is an environmental shift that motivates new work by changing her:

You can “tropicalize” yourself, fertilize yourself and your work in a different weather environment. It can have an effect on attitudes, ideas, even intentions. It gives you different intensities.8

Objects are interesting, but this motion or energy or restlessness is what makes the work lively. Something emerges that’s more than the sum of its parts. It stretches the elastic edge of the universe and makes space. There’s an experience of flourishing diversity here that comes out of travel across differences that can’t or won’t be assimilated. A multiverse that can be made felt by changed surroundings. When the work makes connections across scales, it intimates the wider worlds within which any individual world is held. From the universe into the room, from the room to the body. ‘A being can be a space, one can enter a character as though entering a room.’9

Body

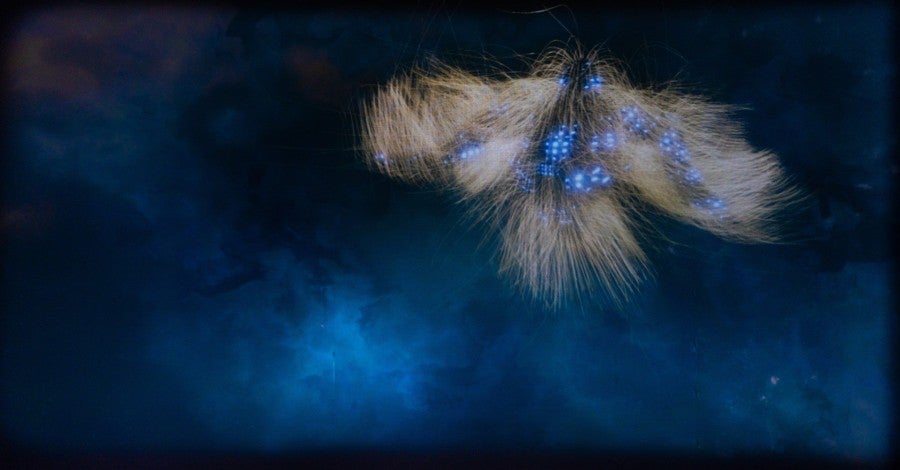

In the beginning my body was floating. There were stars at different distances and they were suspended with me in deep blue. A taupe cloud enveloped my field of vision, it bubbled like a lava lamp, then thinned out until it looked like a gauzy fabric. When I looked down I couldn’t see my body, only more of the softly glimmering abyss, glimpsed through mists. In my ears there were creaky noises. They sounded ancient and had a beat. They were dark-night sounds or perhaps they originated in the deepest parts of an ocean. When I looked up, something new appeared in the farthest corner of my field of vision.

It streamed forward into full view: silver and huge. It had an amoeba-like form but it was definitely piscine. A shoal of fish that was shaped like an enormous fish. Or maybe a single fish whose many scales gave the impression of a shoal. It wasn’t a fish…each scale was a small, metallic silver tab, some kind of building component or beaten mineral. It swam across the screen, flashing like armour, and went away from me.

I looked around, through the veil or scarf or bubble that enveloped me. More space, further glimmering stars. Then there was a fizzing sound.

...I was conscious that there were other people nearby that I couldn’t see.

The comet or meteor, or whatever it was, burned with extreme beauty. It moved, crackling with noise and sparkling, right down the centre of my universe, nearly colliding with, and then passing, the huge silver shoal, which looked heavily solid beside it. The meteor trickled on down, right beneath me, between the deep space where my legs should have been. I turned around to watch it, through wisps of my clouds, emerge on other side. It gathered a train like long links of different coloured fairy-lights, leaving behind a trail of tiny dotted stars that faded out one by one.

When I turned back I saw a writhing monstrous thing. A medusa. A rainbow of electrical flexes, bending rubberily around one another. An evil wig from a schlocky horror. A major jellyfish. I realised that it was coming towards me, horribly slowly. It grew larger and larger, blocking out all of distant space. It seethed closer and closer to my face, until I thought the tips of its tacky-looking tentacles would stick to my head, embracing or smothering me. And then it stopped. It floated calmly nearby, as though it had come to look at me. I felt an unexpected mildness from it. Curiosity, maybe. A thumping heartbeat sound in my ears, which I hadn’t noticed, quietened. Then the taupe bubbles around me grew milkier and thickened, until it felt as though I was contained in some strange skin, a caul or womb. Space spread out around me. Stars glimmered and beat. I waited for the next thing, but instead, I heard the voice of the invigilator who told me that it was all over. Sit still, they said. Somebody will come to remove the headset.

While I was inside the virtual reality of Alienarium 5 I had a strange awareness of myself as multiplied or folded into several places at once. I felt my body floating through the glimmering, creaking VR universe, inside my milky space-bubble. And I was, at the same time, also hyperattentive to my physical presence, headset on, inside the gallery viewing chamber. My surroundings felt more than usually tactile: the plasticky surface of the stool I was sitting on and the soft, slightly warm flex of the headset that pulled across my collarbone. I was aware of myself, sitting upright on the stool, vertebrae aligned, blind. My range of movement felt constrained: I was attached to the floor by my wiring, and I was conscious that there were other people nearby that I couldn’t see.

The gallery attendants gave instructions, fitted our headsets, and when the journey began, they stood back to watch over us. As I floated between stars, I had a distant but steady awareness of their presence, seeing me from this other reality. I was conscious that my spacey visual surroundings were contained inside the room they were in, but also that the room they were in was suspended between stars in deep space, which I could see.

At the end, an attendant helped me remove my headset. They asked me what it had been like in there, and I said that it was intense. They said I’d been looking around a lot, and grinned. I thought about how the invigilator is often silent, only half-seen – a still, quiet presence that audiences and reviewers delete from their account or their memory of the exhibition space. Inside Alienarium 5 there was a subtle shift. The work triggered a chain of small encounters where there would, more usually, be disconnect. The exhibition channelled my attention to the farthest reaches of deep space, but it also made me more aware of my own body and of the others that surrounded me.

Later that day I met Dominique at St Pancras Station. It was a warm spring morning, a few days before Easter. The station was crowded with people and luggage, there was a long, snaking queue at the Eurostar terminal. We stood in the waiting area and I told Dominique about my experience of her VR. The womb and the shoal, medusa made out of electrical wiring . She smiled (she smiles frequently) and said that it was interesting to her to hear how another person experienced it – each story is distinct. She herself would have described the scenario differently. She told me that each headset, of the five in a row, took the perspective of a different alien. The person who had been sitting beside me was the shoal or the meteor or the electrical flex jellyfish. The journey wasn’t a single enveloping environment, but a series of experiments in perspective, each one passing by and making contact with the next. And behind the room there was another sphere of orbit: a viewing chamber where you could watch the people experiencing the show. Dominique found it poignant – to watch the bodies, headsets on, blind to their immediate surroundings as they looked into a fantastical reality that was inset within this one. Her description of the experiment as a whole induced vertigo: shifting chains of difference and connection, across spaces and scales, within the headset and the gallery space, across the park and the city, between planets, spaces, a multiverse, each being an emergent property of its others, and not reducible to them.

Opening channels of attention to that which is alienated is a political process. The work, ‘a situation, rather than a thing’, triggers a moment of awareness – it’s an action. It’s hard to separate an intellectual experience of understanding or increased cognition, from something ecstatic – a trip. Perhaps that’s because the sense of sharp insight can only cut through when it is made felt, when it happens in the body. Gonzalez-Foerster’s work is resistant to description because it’s interested in everywhere and everything, and also because it balances on a delicate possibility: feeling. It’s difficult, in the real world now, to deny the condition of interconnection across scales: body-room-environment-space. Ecosystems, multiverses, or bare life. But it’s not always easy, through the course of an ordinary day, talking to friends or sitting at your desk, to feel the impression of these interconnections – contact cascading across scales, specific points at which the self and its others knit into one another and push against one another. Among the spaces Gonzalez-Foerster has created there is a room which is an autobiography of sorts. euqinimod & costumes first appeared in 2014 at 303 Gallery in New York, and was reassembled for her 2015-6 Pompidou Centre retrospective. It’s a space that contains objects from her personal archive, early drawings and snapshots from her youth and clothing that she no longer wears. In some ways – like many of her works – this room is an outlier: it’s not symptomatic of the fantastical, trance-neon-tropicana-drenched environments she is known for. In another respect, this unusually direct autobiographical work is one that exemplifies how Gonzalez-Foerster makes sense of a world that she characterises, as any watchful person would, by complexity. Each ephemeral sensation has a distinct intensity. euqinimod & costumes draws in a sense of physical closeness. The drawings were made with her own hand and the clothing came from her own body. It’s also an intimate, in some ways a gentle show. The walls are painted in pastel colours, there are mirrors and a few pieces of soft, curvilinear furniture. Each point of contact, carefully placed, can be a hyper-tactile experience. It’s only when they encounter one another that something emerges at another scale: a whole being, a life. There are photographs of Gonzalez-Foerster during the 1970s and a nightgown that she wore as a child. Worn clothing has a curious power. It holds the form of the wearer even after the wearer has discarded it, even after the body has grown out of it. It can cling to skin cells or a stray hair. Gonzalez-Foerster’s work thinks with the whole body. It tunes into minute, incremental plays and patterns of sensation, and this creates presence. The fade of fireworks. Gritty sand. The smell of musk and hair. The glimmer of distant lights. Dancing limbs casting shadows. The tendrils of lush plants, reaching toward one another. An alien call. The sound of rain.