JESUISDESOLEEJENAIPASCOMPRIS. A reflection on truth in Sylvie Fanchon’s painting.

Helena Chávez Mac Gregor and Sylvie Fanchon, Paris, November 2022.

1.

I have a recurring dream, in which I talk to a friend in French. He is a French speaker. Outside the oneiric realm we communicate in Spanish and English. But every time I dream about him, we speak in French. Inevitably, the dream lasts only a few seconds, as long as I manage to speak before I run out of words. Many times, I wake up with my mouth stuck.

I should speak French, but I don’t. I studied it as a child and later as a teenager. In college, I studied philosophy and, as I finally chose to work on aesthetics and politics, I ended up reading endless treatises in that language. But I don’t speak it at all.

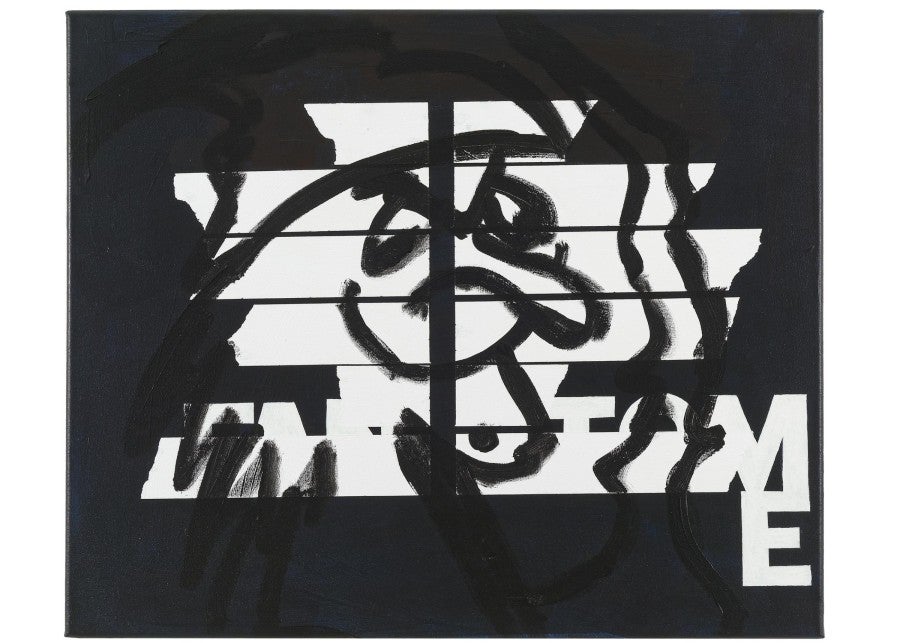

The first painting I saw by Sylvie Fanchon was a black and white bichrome. On a black background, white figures recall the shapes of cartoon representations of animals. A dog, or some four-legged being, walks with its head up on the bottom right side of the painting and a plump little bird leans on a strip of white paint made in one brushstroke, on which a series of black letters made in stencil are piled up to form a set of signs: JESUISDESOLEEJENAIPASCOMPRIS.1

I stared at the painting for a long time, putting the letters together and forming the words. I didn’t manage to form the sentence right away, I had to try several times, using punctuation marks: Je-suis-désolée, je-n’ai-pas-compris. It didn’t seem like a conundrum, but the work forced me to go slowly, perhaps at the same speed that my brain processes the language. I clumsily read the painting. Out of context the phrase didn’t say much, or said so much that I couldn’t place it either. However, the anchorage with the other characters made it less dense. I wondered if the intention of the use of language in the painting was political, as in the work of so many other Francophone artists, where language is a critical or agitational device—Guy Debord, Claire Fontaine, Thierry Geoffroy—; if it was an exercise concerning the ego—Ben Vautier—, or if it was more of a poetic inclination—René Magritte, Francis Alÿs. Inevitably, the phrase Soleil Politique from Marcel Broodthaers’ work came to my mind, perhaps because it was the reference that once hung in a reproduction in my house. I forced myself to concentrate and cling to find the expression of a brushstroke, to feel the color in the painting. After several minutes of pretending to contemplate, I laughed. I laughed at myself and how difficult it is for me to understand painting. I was surprised at how uncomfortable it made me feel not knowing where to stand, how grumpy my clumsiness made me. I looked at the letters again and read out loud JESUISDESOLEEJENAIPASCOMPRIS.

2.

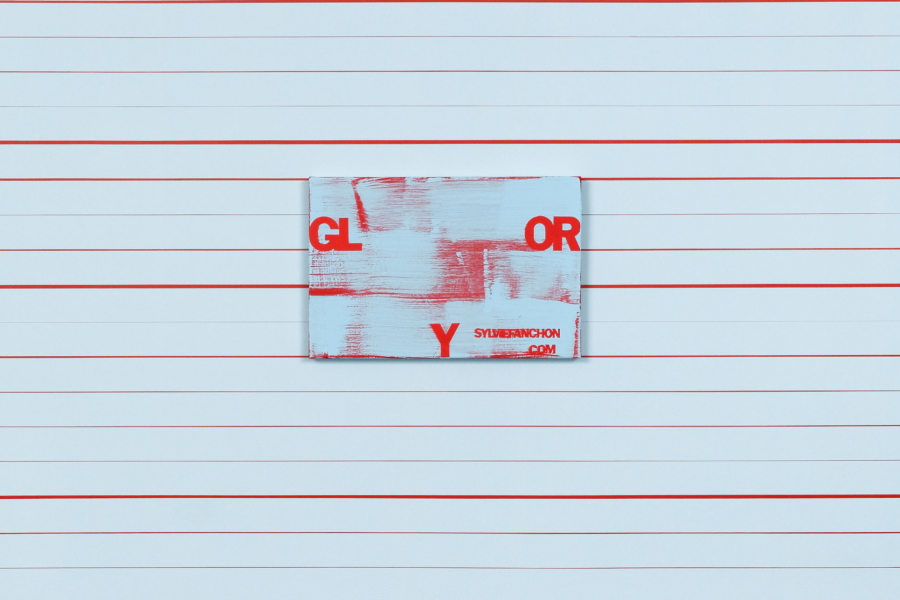

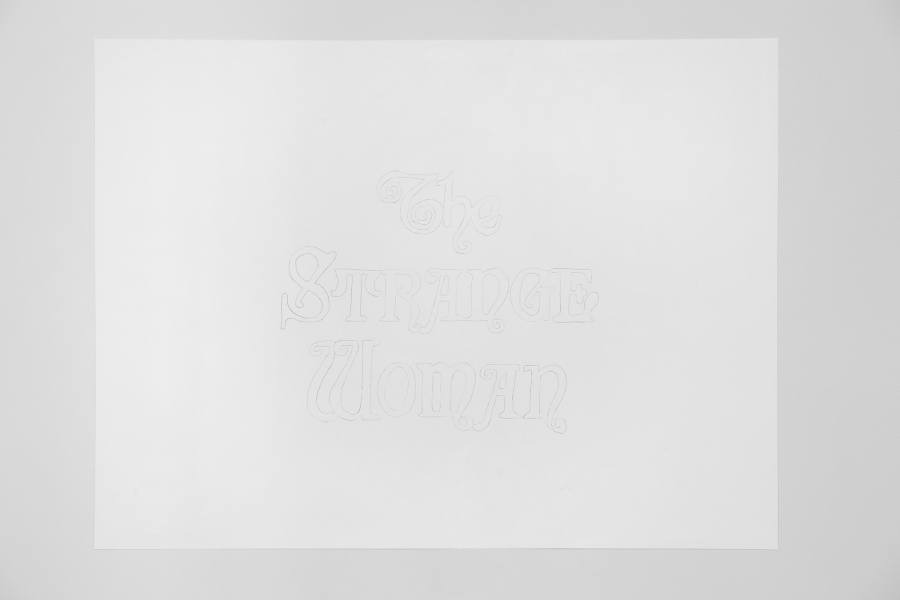

My encounter with Sylvie Fanchon’s work began with a detour, discovering her from some of the spaces that her work inhabits, in and around Paris—the city where she lives. It began in the suburbs, at La Galerie, centre d’art contemporain de Noisy-le-Sec in the Seine-Saint-Denis department, where the exhibition “Hedy Lamarr. The Strange Woman” included two small paintings by Fanchon. A bichrome with a blue background and orange stripes forming the phrase The Strange Woman, title taken from the eponymous 1946 film starring Hedy Lamarr. And the other piece, with the same inscription, but in a different font and carved in the white wall in such a way that the color contrast between the background and the shape was so faint that it almost went unnoticed.2

Next, in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, I visited Bétonsalon - Centre d'art et de recherche. On the external facade there is a permanent installation, or semi-permanent— because the nature of the material makes it ephemeral. There, on the glass surface, using a layer of watered-down Blanc de Meudon (a kind of white paint made with crushed chalk with an earthy texture), the letters JESUISDE/SOLEEJE/NAIRIEN/ENTENDU3 appear as negative unpainted space on four glass panels with circular strokes that recall the movement made when cleaning windows.4

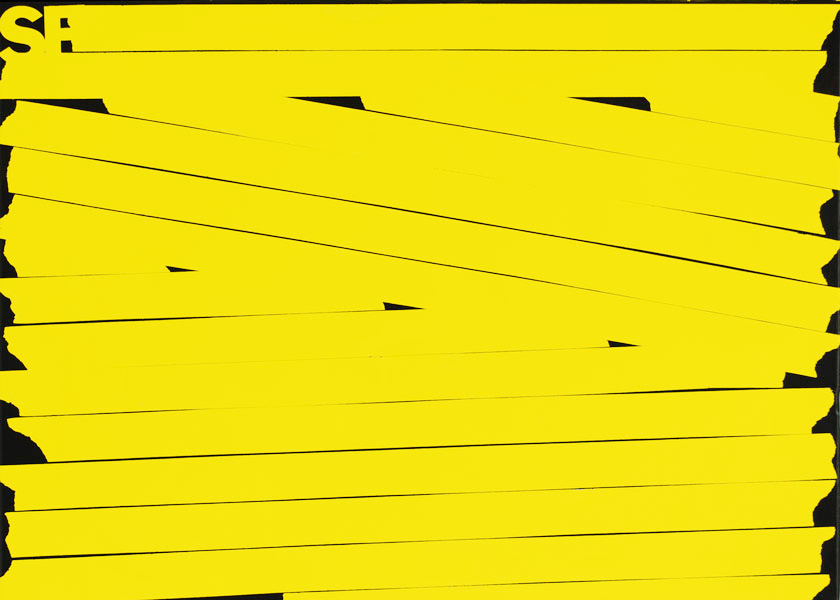

Later, again in the suburbs, at the MAC VAL, Musée d'art contemporain du Val-de-Marne in the town of Vitry-sur-Seine, I found a huge mural with a black background and ‘flesh’-colored stripes—a color that clearly does not exist as there is no flesh color as such, but I would not know how to name it; maybe something between pink, brown and sand, but which my head instantly defined as ‘flesh’ colored, irritating me with the racist persistency of language. Diagonal stripes of the same width ran across the wall beginning and ending in a ripped cut, evidencing the methodology, an adhesive tape stencil.5 On the left side from top to bottom it reads:

S

A

G

E

S

F

E

M

M

E

S

Sages femmes literally means ‘wise women’, but in French it is the way midwives are named. These words coincide with the artist’s initials. Sylvie Fanchon / Sages Femmes / S.F. Was this way of signing her work a coincidence? Could it be a way of establishing a link with a secret community of women?

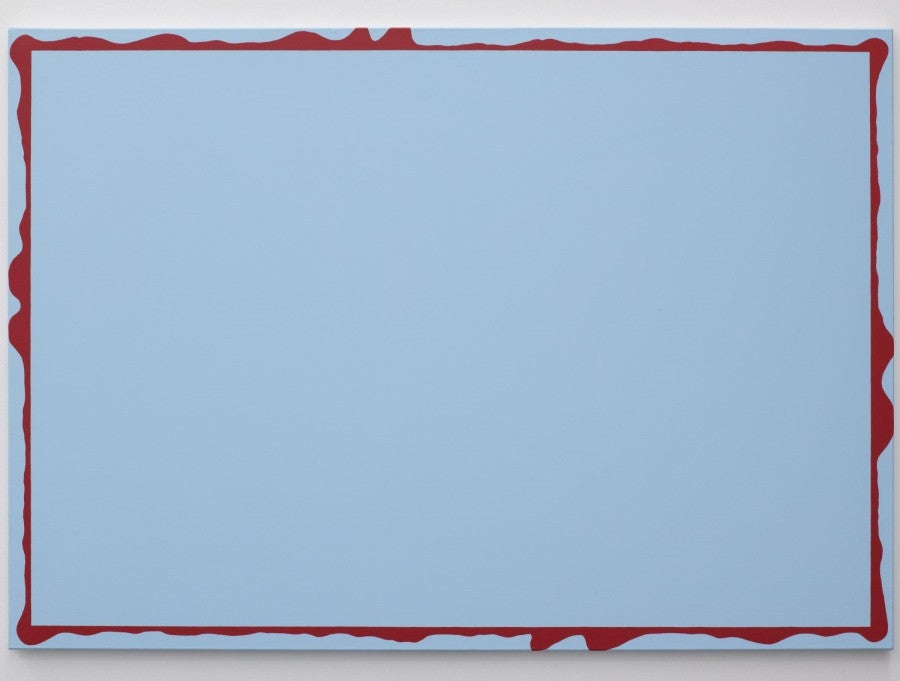

My detour ended in the heart of the city, at the fine arts school, in an office of the École nationale des beaux-arts de Paris. I had never been in such a beautiful art school—so loaded in history. There, a painting by Fanchon was waiting for me. A canvas with a sky-blue background—was it more like light blue? Why is it so hard for me to identify and name colors?—with a small red cartoon figure in the center.6 It was the silhouette of a dog that I had seen many times as a child. I could not remember which cartoon it came from. I recognized the image, but could not place it in a specific context. It aroused a certain tenderness in me, but I had no emotional attachment to it either. Now, while writing this, I discover on Google, under the search “old dogs in cartoons”, that the character’s name is Droopy and it is a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer character.

I usually write about artists that I know well or that I have worked with for a long time.

In this detour, besides intuiting the themes, rhythms, continuities and insistences in Fanchon’s work, I came across something I did not expect. Every time someone asked me what I was doing in Paris, and I replied that I had come to see Sylvie Fanchon’s work, something changed in the look and the gesture of those who questioned me. A smile that awakened the face. It was something subtle, as if the bodies were relieved, as if they regained a moment of contentment. The first time I noticed it, I was curious, but, in the repetition of the gesture, I found relief too.

I usually write about artists that I know well or that I have worked with for a long time. Besides a caution against finding myself in situations where I need to force ideas, to try to say something meaningful about a work I do not really like, I suppose it is also a provision so that I don’t end up working with, or on the practice of, people I don’t feel comfortable with. I spent ten years of my life researching a French philosopher and when I finally met him it was so disappointing that it left me with no room for serendipity. When I was invited to write about Sylvie Fanchon my first impulse was to say no, apart from the aforementioned reservations, I prefer not to write about painting. It’s not that I don’t like it, but I feel somehow surpassed and overtaken by it. However, there was something about Fanchon’s work that made me curious. This, and the collapse of certainties that the pandemic left behind, prompted me to suspend my rules. A few months earlier, an invitation to present at a conference in Johannesburg, which I couldn’t refuse, led me to investigate the work of Frida Kahlo. Focusing on a series of self-portraits, I discovered a marvelous pictorial world that opened up questions, which left me intrigued and wanting more. So, I said yes to the task. Fortunately, the desire to look at other things, to think about other ideas, to learn more about painting, to write about women who paint, was stronger. From these detours and accompanied by the smiles of those who heard her name, I began to delve into Sylvie Fanchon’s work.

3.

Sylvie Fanchon thought that if her career stumbled, it was not because she was a woman but because she was not good enough, or maybe because at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first, nobody cared about painting anymore. However, when I finally spoke with her, she said that she now realizes that her career was determined or at least marked by the fact of being a woman. Could that be the reason why I did not know her? Because she is a painter? Because she is French? Or because she is a woman? Fanchon is not particularly concerned with positioning herself in a history of women’s art, nor in a feminist production. However, I do wonder what women’s painting is. How women place themselves in a tradition, a medium that has been masculine for centuries; where the plots, gestures, and values have not only been created by men but created by a fully patriarchal logic and dynamics. Painting, as John Berger said, imposed specific ways of seeing, which kept a complicity with capitalism—as much as with the objectification of women. After decades, in which this has been pointed out, are there other ways of seeing and producing today? Other ways of painting? Can one continue painting after dismantling the metaphysical, sexist and capitalist logics of the medium?

Fanchon assumes the death of painting with the grace of being out of time.

Sylvie Fanchon sits on the history of art and laughs, not without anger, at the pretensions of sacredness, interiority and contemplation of painting. She also laughs at the aspiration to change the world with art. She seeks truth with painting, but perhaps, unlike other artists, she does not seek truth in the painting, nor truth in painting. This last proposition, which Derrida attributes to Cézanne, reminds us of the knot we are in:

That which pertains [a trait à] to the thing itself. By reason of the power ascribed to painting (the power of direct reproduction or restitution, adequation or transparency, etc.), “the truth in painting,” in the French language which is not a painting, could mean and be understood as: truth itself restored, in person, without mediation, makeup, mask, or veil. In other words, the true truth or the truth of the truth, restituted in its power of restitution, truth looking sufficiently like itself to escape any misprision, any illusion; and even any representation–but sufficiently divided already to resemble, produce, or engender itself twice over, in accordance with the two genitives: truth of truth and truth of truth.7

Truth in painting, in this double genitive, was undoubtedly the philosophical obsession of the medium. Painting comes to Fanchon when it is already mortally wounded. Although this does not mean its end, it does entail the decline of metaphysical aspirations in it. Thus, Fanchon’s questioning does not seem to be an ontological inquiry but a material one. She suggests remaining cautious before the power of fascination and enchantment of painting, and to do this, she establishes three limits from which to work: surface, color and form. With these three elements, which are modified throughout more than four decades of her career, the artist experiments to produce truth in painting. In the painting, in her painting, in every painting. Her work is to insist, almost obsessively, on these components without ever returning to a field determined by the artist’s technical, expressive or intuitive genius in the classical sense of painting tradition, nor to the cold purism of the medium. Here, there is a pictorial research of the first order, which is within the history of painting itself, but already outside its teleology.

Sylvie Fanchon does not make abstract or expressionist painting; she is neither conceptual nor lyrical. Hers is a production that insists on investigating color and form without ever forgetting the delimitation that allows the existence of that work. The space—the canvas, wall or glass—is not a window, but rather a surface. There is something in this search that frees us from the pressures of painting, that relieves. She does not see herself as a feminist artist, but to me it is refreshing to find a woman’s painting that does not follow the male mandate, that neither imitates it nor assumes the place historically designated to female painters. Fanchon assumes the death of painting with the grace of being out of time. Therefore, rather than aiming on geniality, she plays. She establishes a series of rules to play and, from there, to unfold the possibilities of truth present in her paintings. Playing is not a banal nor a complementary activity, it is perhaps the resource that remains once the historical pathos of painting is broken.8

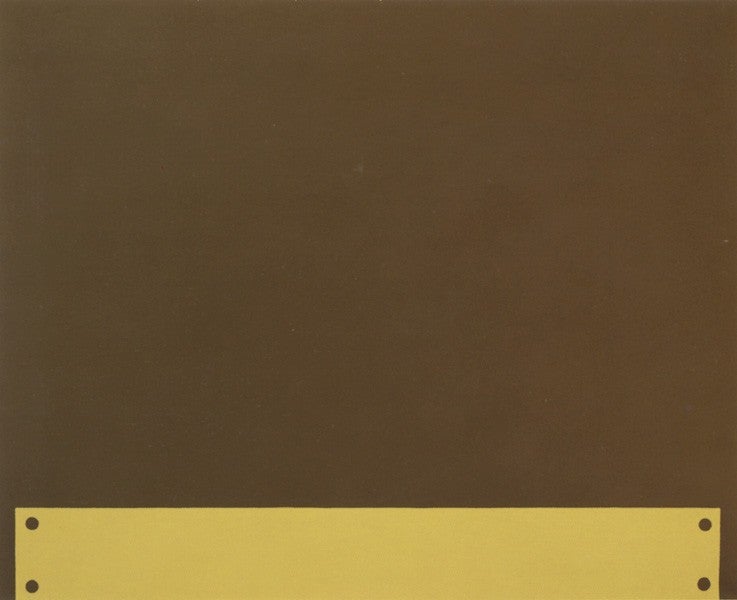

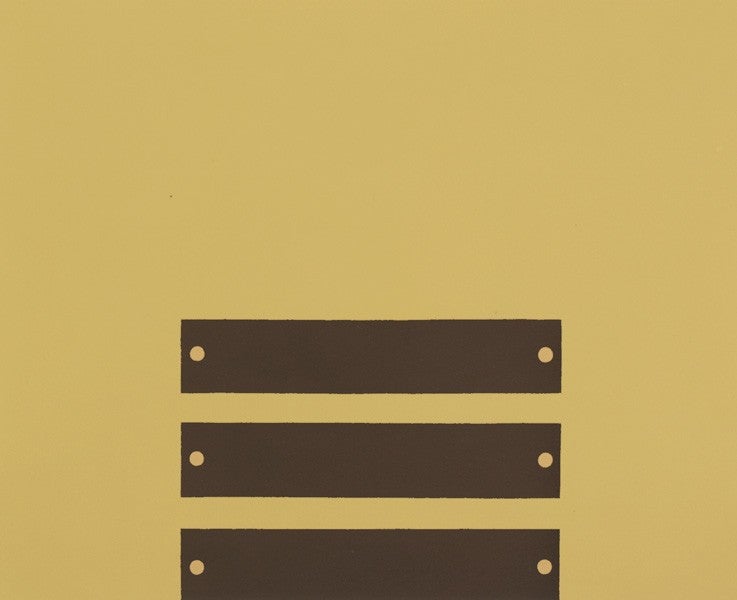

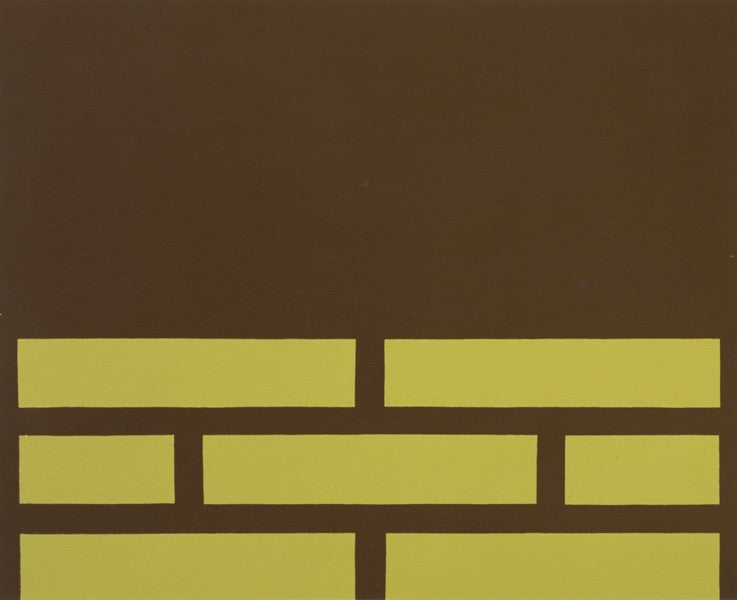

Going back to the elements of her work, from the beginning of Fanchon’s career, in the late eighties, we find that her research is delimited by the surface. She builds from the plane, tracing the area that determines a working space. The frame, the edge in her work, because it lacks ornament, is not an exterior but a limit. In choosing not to adorn it she creates a two-dimensional space. It is interesting how this limit changes in her work. Although in many of her pieces this is determined by the canvas, there is also an exploration that takes it to the wall, where the surface expands. Likewise, there are the glass panels where she explores other materialities, but in which she insists on the condition of the plane as surface. Fanchon’s painting plays with scale and with the functions of the work. In the sense the canvas has historically had, her pieces can be interior—inside a gallery, museum, house—or exterior—the street, the public space. In both cases, interestingly, the rules of the work remain constant. Fanchon does not modify her execution in the face of the pedagogical or spectacular possibilities offered by muralism or street facade.

Her work, contained in this delimited space, focuses on the tension between color and form. On the one hand, in terms of color, she always works with bichrome, creating visual games between two colors. This is perhaps to mark a certain affinity with minimalism, but refusing to endow with a single color alone the weight of an individual object. Her experimentation proposes composition games. Even if the viewer only sees two colors, in reality, there are several colors contained in the work. With the colors, the artist seeks neither the creation of density, nor of light, nor of dimensions. Nor does she pretend to affirm the medium as an instance of visual purism, much less to express or provoke feelings; her artistic practice lies in pointing out the game of what appears in between. In their crossing, their opposition, their tension.

In Fanchon’s work, the silhouette figures operate as appropriations and copies of symbols, letters and figures.

There, the third element in her work emerges, the form. Although Fanchon works with representations, they do not seek a realism that allows affirming the thing’s truth. There is no substitution or mediation; on the contrary, her forms are appropriations of signs removed from their contexts. Fanchon’s forms are silhouettes, and there is much that is uncanny in them since, at least in my Latin American tradition, they are reminiscent of the graphic-political exercises that pointed to missing people.9 The silhouette is that which appears in the place of the disappeared. That moment taken from children’s games of drawing the outline of a body lying on the ground, going around its silhouette and then removing it to keep its double. Sometimes we are left with only the double. The silhouettes in Fanchon’s work are produced with stencils, a methodology associated with street painting such as graffiti or in artistic-activist practices where the stencil is used to create repetitions in hurried situations, and where the technique does not matter and the ideal of the original is not pursued. In Fanchon’s work, the silhouette figures operate as appropriations and copies of symbols, letters and figures. These silhouettes are recognizable, but they are distorted and their meaning, therefore, deferred.

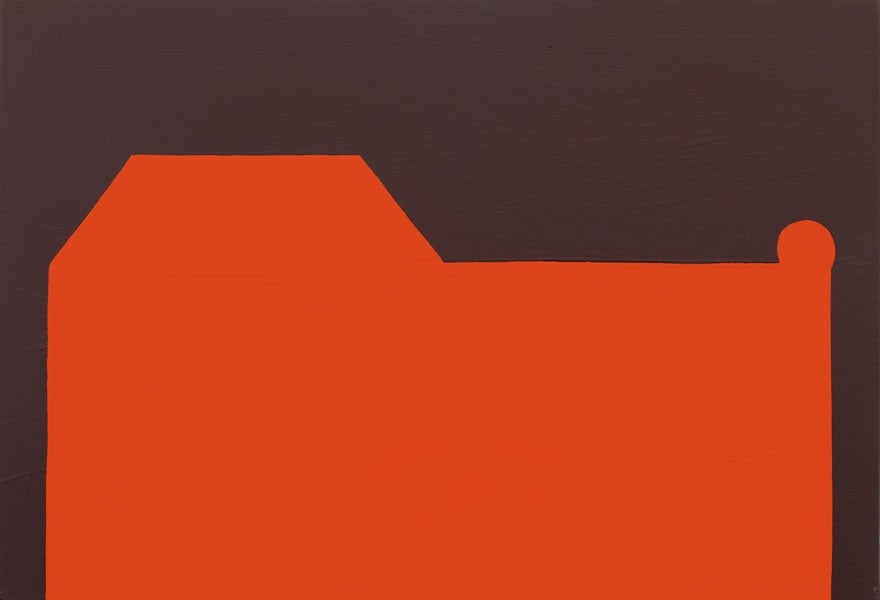

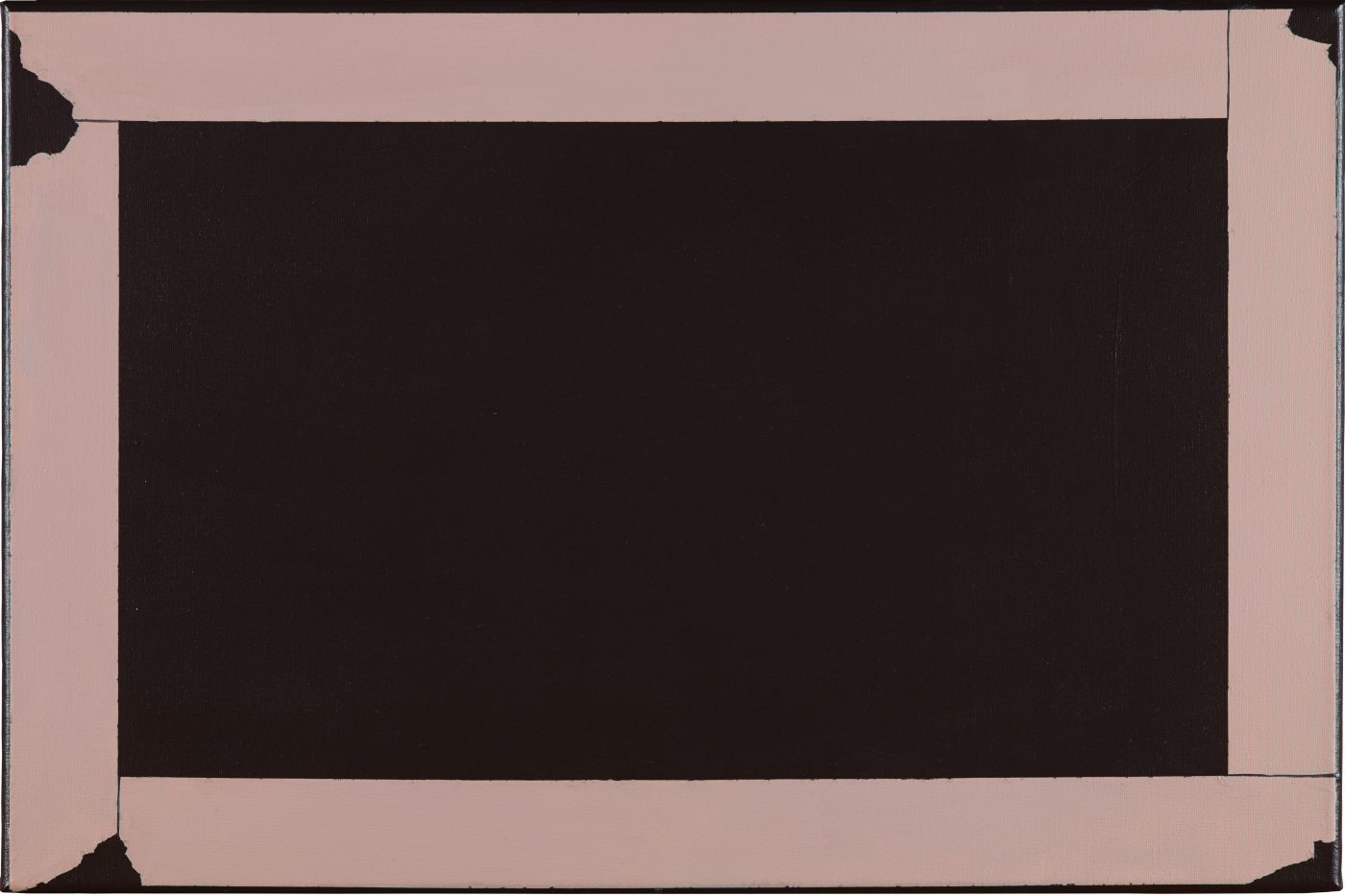

In the 1990s, the forms that emerged from her bichrome were geometric or architectural figures, squares and rectangles that could be the outline of a house or a plan for the construction of an object (Untitled, 1994); later they became botanical motifs, the outlines of some sort of plants and grass (Untitled, 2007), but also decorative ornaments such as frames of different shapes, sizes and colors (Untitled, 2008), busts that resemble old sculptures or unformed stains (Untitled, Aspects 2012) or haircuts of long and stylish hair (Untitled, 2017). In Fanchon’s work these depicted ornaments—decoration and adornment —detach what has historically been taken in painting as that which is additive, external to the representation of the object, to put it in the center, to make the whole painting, and the truth that it can produce about it. In the 2000s, the silhouettes shifted from the outline of animals (Untitled, Aspects, 2012; Untitled, Tableaux bêtes, 2009) to those of cartoon characters, (Untitled, Caractères, 2010). This allows another game that intervenes in the pictorial tradition in that it introduces humor from these figures devoid of any drama or expressiveness. They are not the characters in vogue or belonging specifically to French culture. They are, rather, elements of a vaguely common, standard, global culture. I show them to my six-year-old daughter and she can recognize the outlines of them—a bird, a dog, a coyote—but she doesn’t know the specific references. This is where Fanchon’s work operates, in being able to sit in the history of painting to play and warn: “I introduce a dialectic with the help of futile, caricatural figures from the world of images. It is a 'warning', a way of saying 'let us remain vigilant' in the face of the seductive power of painting.”10

In this same sense, language appears in her work. With it, she does not intend to dictate the truth or her truth, nor to propagate a slogan, nor postulate, much less to communicate a feeling or idea. Language is again a symbol that she appropriates in order to disavow it of its power. Without spelling or grammar, she gets on language’s nerves. As she puts letters together, unfollowing writing conventions, the referent becomes strange, ambiguous.

Although Fanchon’s body of work, after more than four decades dedicated to painting, is very extensive and complex, it seems to me that these are the elements that delimit her universe. As if they were the components and rules with which she decided to play and establish a game with the viewer. It is from there that she sits in the history of painting, she is in it, but also beyond it. Her truth no longer has to do with validating a tradition, but with finding the logic and rigor of her own operation. She does it seriously but not without grace, she is constantly laughing at us and at herself.

4.

A few months ago, I was at a friend’s house with our respective children. The children were playing while we were talking. Their game was a sort of dance contest, where each one of them could play their favorite song. I hadn’t paid much attention to how the game operated, until the screaming made me realize that part of it had to do with which of them Alexa obeyed. Each child was shouting a song to Alexa, Amazon’s virtual assistant, to play. The voices were getting louder and louder, and the children’s tone became aggressive as she didn’t recognize what they were saying. After a few minutes of watching the show, I stopped to tell them not to yell at her. It annoyed me to see how they were talking to a woman, even if it was a simulation of one. Why is it that all virtual assistants have a woman’s name and voice? Does that insist on women’s labor in care work ? Does the cold and aggressive tone with which we relate to them validate in children the very possibility of violence towards us? I wondered all this as I helplessly watched how my friend’s son yelled, “Alexa, turn off”.

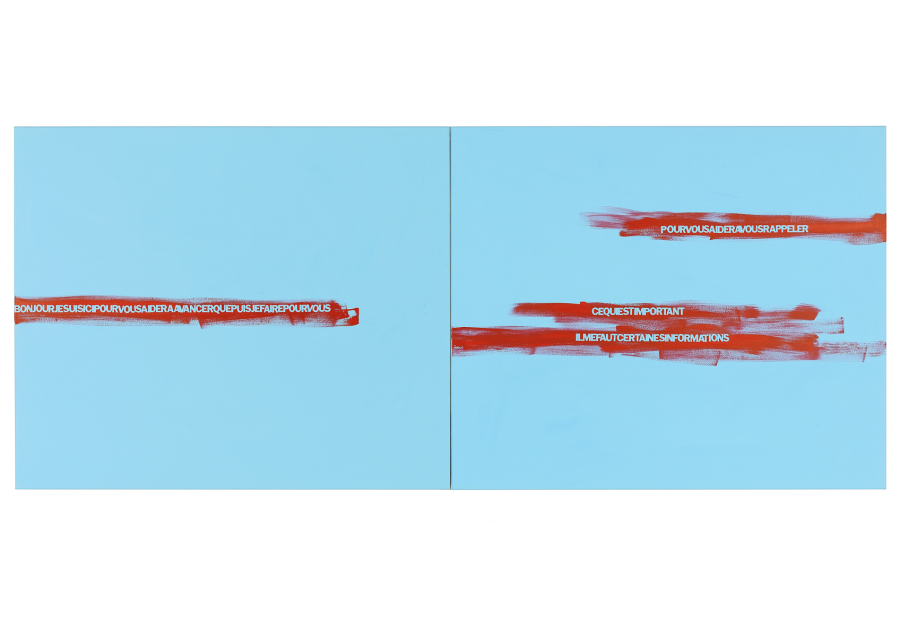

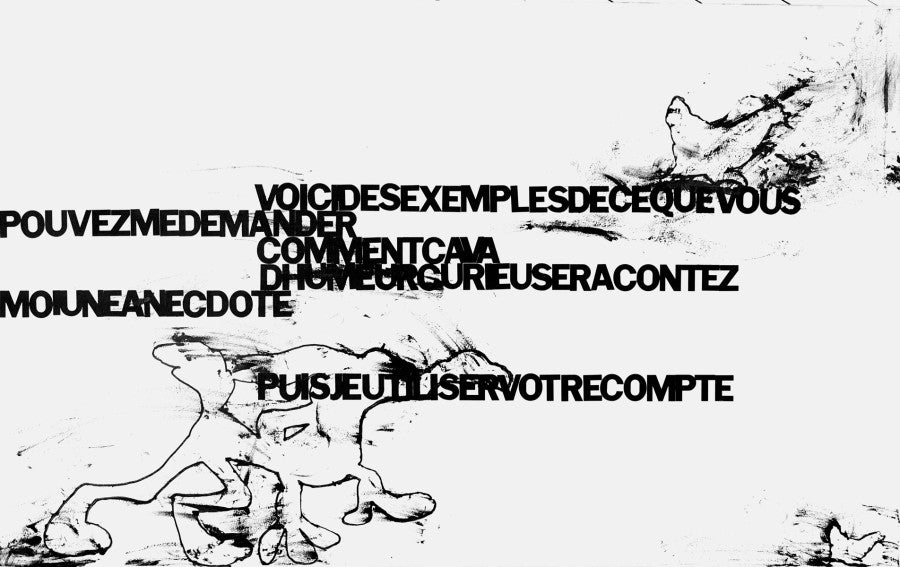

JEMAPPELLECORTANA/QUEPUISJEFAIREPOURVOUS.11 It is 2014, and Sylvie Fanchon comes across a new artificial intelligence service automatically downloaded to her phone. Her name is Cortana, and she introduces herself as Microsoft’s “personal productivity assistant”. She helps users find sites of interest, social networks and services. She does so, like almost all such forms of artificial intelligence, using a helpful tone—available in several languages—and by asking questions that, in their logical simplicity and linguistic awkwardness, become existential queries.

Cortana is originally the name of an ancient Scandinavian sword, which was used to name the artificial intelligence character in the Halo universe. There, Cortana is built by cloning a woman’s brain, although she has no physical form—she is just a voice. In the game, Cortana was designed for espionage and infiltration purposes. She is described as an intelligent and lively “being” with a sense of humor. She is loyal to humans, perhaps because she herself is a clone. Therefore, to create a personal digital assistant, Microsoft has used the character of that saga, and intends to propose a more personal service, which can compete with Siri or Alexa. Its most remarkable function, we are informed, is that she allows you to remember things. You can tell Cortana to remind you of anything.

Fanchon uses the phrases that this operating system has thrown at her. With them she has built the Cortana series since 2017. Words are the central characters of the pictorial spaces in this series. Their appearance in the game of bichrome is produced with templates, stencils in this case of letters, which allow its precise production. It is not the artist’s handwriting, it is a common typeface, that can be replicated uniformly in the different pieces of the series. Cortana’s sentences are appropriated and reproduced by Fanchon, always appearing in capital letters and without punctuation. Thus, there is no indication marking the beginning or end of each word. The mechanicity of language in the operating system works in its pictorial decomposition as a creator of estrangement. POURVOUSAIDERAVOUSRAPPELER/CEQUIESTIMPORTANT/

JESUISDESOLEEJENAIRIENENTENDU/JESUISDESOLEECONNEXIONIMPOSSIBLE/

ETSINOUSDISCUTIONS/DITESMOICEQUEJEDEVRAISSAVOIRAFINDEPROTEGERVOTREVIEPRIVEE.12

The figures chosen by Sylvie Fanchon, whether animal forms or letters, do not pretend to be representational but serve as a cultural and epistemological index, perhaps a punctum in a moment of the world. On the surface of her painting appears the absurdity of representation and truth in artificial intelligence. It would be funny if it were not grim. AI has come to stay, Fanchon’s Cortana paintings will be a reminder to beware of the enchantments of them.

The language Cortana uses is one of those futile silhouettes drawn from our world of representation, the appropriate double of our shared culture’s absent referent. In its simplicity, Fanchon shows us, with delicacy and humor, that there is no natural principle. This allows us a joyful detachment from metaphysics. The beauty in Fanchon’s work is not in the truth in painting, in relation to the thing or being, but in the joy of having freed ourselves from it. With it the true truth, the truth of truth, has been broken.

5.

Painting, so masculine, so metaphysical, so patriarchal, can become, as in Fanchon’s practice, another thing. A practice that is free.

When I first met Sylvie Fanchon, she had stopped painting. She told me so without sadness. She was done, at least at that time, with it. She kindly showed me the drawings she was making. Besides the dimensions and texture of working on paper, perhaps the most significant difference from her painting was that of the game of colors produced between the color of the surface itself, white, and the pencil that colored the paper in different tones and intensities of gray.

In these drawings, there were phrases that I had not seen before in her work. In the case of the drawing that most caught my attention, the words, now in English, formed the set THESHOWMUSTGOON. Above it, emerged the silhouette of a smiling cow.13 It took me a while to recognize it, but eventually I was able to associate it with the image of a brand of cheese that my daughter likes. Also, still hung on her studio walls, there was one of her latest paintings. Near the silhouette of a dog, appeared the letters KEEP/UPSPIRITSYOUR.14 In its tearing and rearrangement I was able to locate a type of language, or rather a use of language, that has become part of a dominant culture. That which, in its authority and its cruelty, denotes a regime that pretends to make us responsible for our well-being. Linguistic strategies of the as if type that seek to anchor in us the responsibility for our destinies. As if it were one’s will that allows life to continue or to end. I remembered those moments of pandemic when I was instructed in those unbearable expressions intended to be declarative statements: “The show must go on”. Is this a show? Whose show? For whom? Why must it go on? What is it that must go on? I also remembered the fury in my friend Sonia’s eyes when, dying of cancer, someone told her to keep her spirits up, that it would help her to recover. As if it depended on her spirits whether her cells would multiply or not. After visiting Sylvie Fanchon’s studio, I called my sister who is an oncologist. I asked her why doctors said such phrases. She thoughtfully replied, “Sometimes we don't have much to say, but it would certainly be better to remain silent.”

The language, extracted from writing conventions and found in Fanchon’s drawings, allowed, as in the Cortana series, a detachment that releases a laugh at the nonsense and obtuseness of the linguistic operation and the existential imbalances that playing with language caused. The mismatch between the smiling cow and the authoritarian statement created a gap. Humor appeared in it, but not without a hint of irritation and sorrow.

These works insist on the truth of the art work, in dismantling its pretensions and authority. Painting, so masculine, so metaphysical, so patriarchal, can become, as in Fanchon’s practice, another thing. A practice that is free. When Fanchon paints, she plays, has fun, enjoys herself. She is also angry, but that does not take away the pleasure of playing and including us in it.

The morning I visited Sylvie Fanchon’s studio turned into afternoon. We reviewed the works she had stored there. One by one, we went over her techniques and the reasons that had led her to making them. She showed me the stencil shapes she keeps in a folder, where letters of various sizes, and cartoon characters, are piled up. She generously spoke to me in English, although, after a while and about certain things, she would switch to French. There are things that one can only say in one’s own language. Time went by in talking not only about art, but also about our daughters—what it means to be mothers and to be artists. About work and care. We also talked about our mothers and fathers, our inheritances and legacies, the places where we were born, and how to live in the times we are living. About what the pandemic did to us, and what we have lost. For Fanchon, these intimate detours are not part of her work, but for me they are important to know when I write about her. It is only from there that I can think about the truth. A truth that no longer pretends to be universal, not even true. Perhaps only possible, thinkable, speakable, shareable.

Now, while thinking and writing about Sylvie Fanchon’s work, I realize that I am smiling too.