“It is my job to create universes, as the basis of one novel after another. And I have to build them in such a way that do not fall apart two days later. Or at least that is what my editors hope. However, I will reveal a secret to you: I like to build universes which do fall apart. I like to see them come unglued, and I like to see how the characters in the novels cope with this problem.”1 – Philip K. Dick, How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later

In 1978, sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick wrote a short essay on fictive universes and subjective realities. Mindful of the authoritarian power of fiction and imagination, he set forth to expound on the danger of spurious realities manufactured by the media, governments, and other interest groups in order to exercise control over mass behavior and perception. He pictured a potential future where communities and individuals no longer had the ability to acknowledge or comprehend realities beyond those that they have been exposed to, leading to a communication breakdown within society. Four decades after this insightful piece was written, the way our world is mediated, represented, and simulated through technology and media has become much more intricate, while the mechanisms beyond what we can see are also much more abstruse. Not unlike Dick’s own craft, artist and film-maker, Neïl Beloufa has been creating micro-universes through his work, as a way to scrutinise commonly accepted ideologies and suppositions that uphold what we understand as reality. In Beloufa’s eyes, these representations pervade our everyday experience like propaganda through newspapers, advertisements, and screens2. They are presented to us no longer as autonomous individuals, but rather as viewers and consumers.

As an artist who firmly believes that his job is to represent society, Beloufa seeks to critique the complex network and systems of power. Moreover, while doing so, he also acknowledges his position, as well as the risks of legitimising the said values or positions he questions, within the worlds he appropriates. Contained within his films and installations, Beloufa’s fictive universes are well-composed layers filled to the rim with nuances, where meaning and positions of power are constantly fluid and in contradiction with each other. His deliberately fragmented scenarios are derived from, and regularly made in collaboration with, a cast of real and fictitious characters. Examples include suburban teenagers in France for Vengeance (2014) and real cowboys and gangsters in Los Angeles in Tonight and the People (2013). Additionally, these scenarios explore the manifestations of cultural hegemony at work. Throughout this process, Beloufa lays bare the ways in which power is acquired and expressed within politics, technology, lifestyle choices, celebrity culture and identity politics. One by one, façades are dismantled under his laborious and impish treatment. His caricatured subjects find themselves in behavioural loops, where everyone is caught in an impasse and the situation implodes. Calling to mind Dick’s analogy of building universes and having them fall apart, Beloufa’s creative and destructive act embodies his process of unpacking the asymmetries of power concealed by the deft strategies of control.

1.

“I like when things get stuck, when there is something to unblock. As soon as it fits in, I need to move on”.3 – Neïl Beloufa

Beloufa’s works are interventions in reality which aim to short-circuit the status quo...

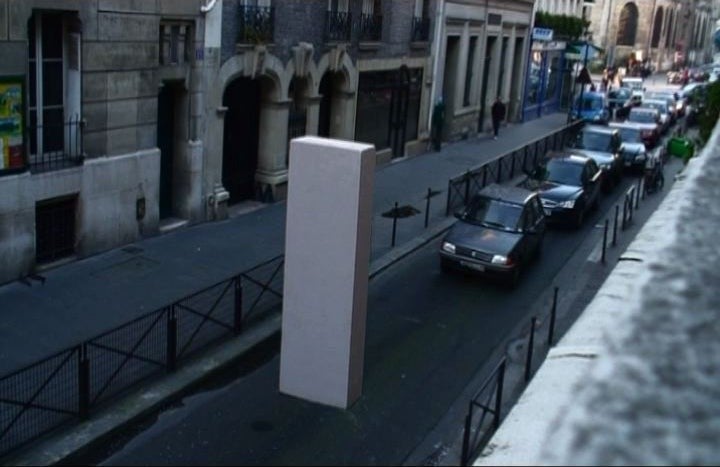

Neïl Beloufa’s works are interventions in reality which aim to short-circuit the status quo of a given scenario or familiar phenomenon. As opposed to being counterpoints, these intentional disruptions function as tactics that rupture routines and enable us to confront deep-seeded conventions that otherwise go unquestioned in our society. The misgivings of image production come into question through Beloufa’s deliberate techniques of inserting or editing out elements as a ploy to unsettle existing visual ideologies. Take for example one of his earlier video works, April the Second (2007), in which he documents road traffic in a Parisian backstreet which has been blocked by a towering plinth. Frustrated, the drivers pause and wait for the hoax to end, however in Beloufa’s take of the prank show Just for Laughs, the joke’s climatic revelation does not happen. Instead, real life hurries on. The video carries forth with instances of stranded cars excruciatingly reversing out of the street to escape, ending with the fire department intervening to clear out the alien structure. Using the familiar tropes of candid camera shows, not only are the motorists in the action tricked into participation, but we, as viewers, are caught in that momentary suspense, thinking that we, too, are part of Beloufa’s creation. In this gesture of disobedience, Beloufa’s simple intervention exposes the blurred line between reality and reality television, as well as contemporary image culture – a domain he consistently returns to in his works.

The street scene is revisited from a different vantage point in The Analyst, the researcher, the screenwriter, the CGI tech and the lawyer (2011), as a red truck takes centre stage and guides us through the visual terrain of a North American suburban city. The grainy aerial footage, which uncannily resembles live police car chases, is accompanied by different voices offering narratives of what is on camera, as though they are crime experts or news commentators. The title gives an indication of the kinds of experts summoned for the voice-overs. By purposefully providing the narrators with no context, Beloufa takes advantage of the cognitive delay between the footage and the narrative, opening up a space for speculative interpretation in the form of a social experiment. As the camera traces the vehicle’s trajectory, the inferred storyline starts rather innocently with the suggestion from one commentator speculating that the driver of the truck left the house after a fight with his girlfriend. The plot veers to a deviant course, with a different voice-over positing a probable kidnap, whilst another narrator comes to the conclusion that the area in which the vehicle is located could be a breeding ground for terrorist activities. These discordant accounts are punctured with lapses of doubt about why the car is being filmed, or personal theories dispelling the truck of any criminal involvement due to its flamboyant colour. The ever-changing commentary demonstrates the instability of perception despite one’s convictions of his or her truths, evinced by professional dealings with information and interpretation. Almost like an ongoing Rorschach test he has orchestrated, Beloufa makes evident the arbitrary power of mediation, and the long-lasting impact on how these generated images and ideologies inform the prejudices and assumptions that continue to find roots in the contemporary psyche.

2.

“Devotees of reality leave all this as it is; they go walking in it, as it were – they « live it ». They seem to accept it, or at any rate never raise a voice of protest against it.”4 – Hans Belting and Alexander Kluge in Conversation, ‘The face cannot be captured by images’

As a discerning observer of the way images have a grip on contemporary life and imagination, Beloufa’s efforts to decrypt the mechanisms of media culture is not limited to laying bare these structures through replication. He also draws focus on the people who are, ultimately, the nodes of reception and distribution of his meticulous communication chain. When planning his first feature-length film, Tonight and the People (2013), Beloufa sent out a casting call in Los Angeles for roles – namely, cowboys, gangsters, political activists, hippies and teenagers – which could be regarded as a microcosm of America seen through the lens of Hollywood cinema. Surprisingly, some of those who auditioned were amateur actors who wanted to play a screen version of themselves in real life, forming a strange cycle of self-identification and typecasting where life imitates art, or, one might argue for Beloufa’s purpose, where art imitates life. The script and character treatments were gleaned from these auditions and they created a patchwork of timeworn American stereotypes caught between reality and fantasy. The film’s motley crew of characters all appear to be whiling away in their own natural surroundings as they prepare for a massive, life-changing event that same evening; wealthy teenage girls gossip while getting ready for a night out and two sets of small-time Latino and black gangsters flirt with the cute young waitress in the drive-in, their exaggerated machismo on full display.

For most of the film, the various characters wax lyrical about their philosophies and ambitions, and their self-indulgent platitudes sound all the more unseemly when juxtaposed with the kitsch and flat Western- and sitcom-inspired film set. As the storyline progresses, we begin to discover that the idealistic characters are all bark and no bite: the cowboy explains to his son the reason why he is not a real cowboy (he did not want to kill anyone), while political activists in a group session caution a fellow black activist – whose urgent rally speech zeroes in on class and racial injustice as the root of the country’s political problems – that bringing such rhetorics back into the political equation will do nothing to change the state of affairs. “America is founded on dreams, not class,” they remind him. All trapped in a junkyard of unrealised dreams, their chance comes after daybreak. Most of humanity is wiped out by the apocalypse, and for those who are left standing, a brave world of possibilities awaits. For once, their dreamed future is real and palpable, but in true Beloufian fashion, this dissipates quickly into a heated debate about whether they should forsake values and frameworks of the past and imagine new systems. Failing to mobilise a path into the unknown, they find themselves heading towards where they left off, a society where banks dominate, organic food is all the rage, and ideals are expressed rather than put into action. Tonight and the People is an uncanny parody of the democratic zeitgeist, banally retold in the same stale rhetoric, mannerisms and aesthetics of a typified world and cultural genres. How can one imagine alternative futures in a world saturated with consummated dreams designed for mass consumption? The irony of Beloufa’s meta-reality is not lost on us. It is a cautionary tale of a dystopian world caught in its own neoliberal fantasy.

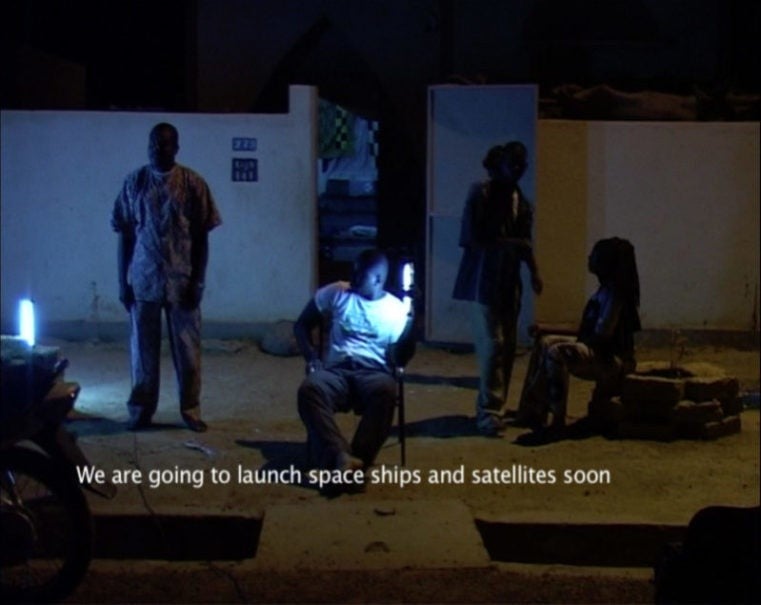

During my studio visit with Beloufa he spoke strikingly about his belief that imagination is the most potent power in a time encumbered by the immense lack of it. Out of his catalogue of films, the realm of imagination is perhaps explored to its fullest extent as a device of subversion in his debut Kempinski (2007). Conceived as a documentary when he was still a student, here Beloufa invited Malians living near Bamako to speak about the future in the present tense. The future-cum-reality they articulated no longer adhered to the image of Africa as a land of technological backwardness, but as a fantastic portrayal of a highly advanced society where physical intimacy happens telepathically, and ideas, objects and bodies move at sonic and light speed. Under the hues of neon lights, their physical reality recedes into the darkness of the night and their powerful imaginations are described and shared in the company of their community. A contrast to Tonight and the People, the tales in this pseudo-sci-fi exemplify how imagination could be harnessed by individuals as a transformative tool to disrupt power hierarchies underlined by Western popular culture and their imagination of the Other within the parameters established by Beloufa.

Yet, one cannot overlook the power Beloufa yields (and acknowledges) as the mastermind of these fictive worlds and self-generative systems, in spite of the fluid and collaborative methodology he adopts with those involved in his projects. Indeed the artist himself has no trouble problematising it. One such instance of the dynamic struggle of control and authorship between Beloufa and his subjects plays out in Vengeance (2014), the outcome of an invitation to work with a group of difficult high school teens from a Parisian suburb. Instead of instrumentalising these students, he practised a laissez-faire approach, asking the students to collectively work on a story they wished to tell, with the intention of lending his artistic and filmmaking skills to help materialise their narrative. What they came up with was a telenovela involving a love-triangle between the self-obsessed Cristiano Ronaldo, his neglected fiancée, Amira, and the romantic wrestler Rey Mysterio, all played by Beloufa’s studio staff. Along with Ronaldo’s treasured robot, the plot unfolds across a world of private jets, fast cars, luxury homes and gyms, and is staged using makeshift materials in the school. However, tensions arise when the students disagree with Beloufa on elements of the film, such as Ronaldo’s favourite food, to be served by Tokay the robot. The students reject Beloufa’s suggestion of a banana, and insist on using popcorn which for them is what Hollywood actors eat on screen, and eventually the class dissents and loses interest. With the class turned against him, Beloufa takes the helm and finishes the piece with a computer-simulated English voice-over atop the original French narration and discussion with the students, arguments included.

Foretold by the work’s title, retribution takes place both on- and off-screen because of a betrayal. The latter is the consequence of the breakdown of Beloufa’s self-imposed position of neutrality in a democratic framework within a social economic reality – the majority of the suburban students are from former French colonies – in which a deviant fantasy outside popular cultural representations has little currency. It is the triumph of Hollywood’s indoctrination over the imagination of the contemporary youth. In the end, the youth can opt out of his universe due to creative differences, but the artwork has to go on. And while Beloufa is at it, he chooses to display everything in his final artwork, setbacks included.

3.

« A paradoxical situation arises when a museum predicated on producing and marketing visibility can itself not be show – the labour performed there is just as publicly invisible as that of any sausage factory. »5 – Hito Steyerl, Is a Museum a Factory?

It all sounds too good to be true. And it is.

Still, how does Beloufa grapple with the double bind of contemporary art which capitalises on the socio-economic critique and turns it into fiscal value through a work’s own process of becoming? Acutely aware of such entrapment, he treats the works he creates for exhibitions as autonomous objects, achieved by mischievously refusing to contribute to the economic valorisation of his own works. This attitude can be traced in the way he haphazardly assembles his pretend film sets which he extends into immersive installations and junky sculptures. They are often amalgams of standardised building materials and scraps, including waste matter that bears witness to the studio’s human activity, for instance cigarette butts and pizza boxes, constituting value out of apparent uselessness. The brazen combination of industrialised and human processes comes together in scrappy and outlandish configurations in the form of visual puns in space, namely the Tron-like6 metal grid he made for his installation Data for Desire (2016), or the blown up iPhone-inspired screens, encased with rubbish from the studio for his last exhibition Content Wise at Balice Hertling (2017). For his presentation of Vengeance in his show Counting on People at Stroom in the Hague (2015), he constructed a lattice of CCTV cameras and miscellaneous objects, played in parallel to the film. The objects were activated in correspondence to the dialogue in the film and, caught by the matrix of cameras, generated a dizzying web of surveillance feeds that criss-crossed the central film projection. When entering the installation, it was as though one had walked into the bowels of this surveillance system. By doing so, one was forced to negotiate the physical space and the sight lines of the cameras, distorting a singular film viewing experience for each individual. Just as everything is on display to us just at the touch of our fingertips, Beloufa addresses the discrepancy in the representation of transparency enacted on social media and its implementation through this regime of surveillance in contemporary culture – and the installation makes a poignant reference to that schism.

Visibility and surveillance as forms of societal control are probed in-depth in an earlier film installation, People’s passion, lifestyle, beautiful wine, gigantic glass towers, all surrounded by water (2011), which revolves around a waterfront complex of glass towers in a prime location in Vancouver. The film focuses on the material and cultural connotations connected to the notion of transparency, and takes the appearance of luminous advertorial of glass architecture featuring buoyant locals and real estate agents lauding the perfect lifestyle afforded by this utopia. In this mythical living environment, work-life balance is not a pipe dream but a reality. Conjured collectively by the interviewees from a combination of ad-libbed fact and fiction, it is crystallised into an idealised space where class differences cease to exist, and its inhabitants have night-long conversations over wine that keeps one in a perpetual state of tipsiness and, not unwelcomed, inebriation. As one protagonist in the video puts it: “Nothing says class, romance, human ingenuity like a city full of glass towers. When I see a city full of these glass towers, I see a world-class city, instead of a hodgepodge of buildings.” It all sounds too good to be true. And it is. With a blend of fantasy living and sales pitches, the film exploits the neoliberal imagination and puts it into question in the glasshouse, where the transparent pane is the only barrier between us and the world, and each other’s lives. The presentation of the video further expounds on the proliferation of the allure and threat of this world of transparency by projecting the film footage into a series of modular kinetic screens. As a result, the utopic image of our future shatters in multiple pieces of light and shadow across the planes of transparencies, as though the viewers are experiencing it through a hall of mirrors. Through Beloufa’s treatment, the seductive fantasy of nebulous living, where everything is out in the open, becomes nothing but opaque and impenetrable.

Beloufa’s quest to dismantle structures of visual and ideological production and the societal structures they bolster, is essentially a pursuit of autonomy from the forces of economic and political control. Invisible to the audience, he has been working adamantly towards creating a space of emancipation and support for his studio and those who assist his productions. To this end, in 2015, he puts this system to the test by moving the studio to an abandoned packaging factory in Villejuif, in the outskirts of Paris, to work on the self-financed film project Occidental (2016). For the full-length feature, Beloufa’s team meticulously constructed a hotel set out of MDF from scratch with stylistic references to hotels of the ‘70s, and began filming this self-initiated project with no destination for its presentation in mind. In line with Kempinski’s critique of the West’s exorcising gaze of the non-West, the title refers to the first hotel chain in the world – the film’s story takes place within the Hotel Occidental and is a nod to the heyday of pre-Airbnb mass tourism, where cultural imperialism took shape in the form of majestically-named resorts and hotel chains all over the world. The plot centres on a high-stakes game between the hotel’s suspicious guests—two fake Italians, a British bachelor party and others, alongside the watchful hotel staff—set in a neutral yet politically-charged space. A protest is raging outside, while inside a different power play of paranoia and control unfolds in a high-octane thriller slash black comedy in a post-colonial society of surveillance and racial politics.

After shooting wrapped, Beloufa repurposed the film set and the adjacent white cube space into a contemporary art space, Occidental Temporary, opening it as an alternative exhibition venue for a community of artists he shares affinities with. By funding it independently from his own resources, Beloufa played the system and carved out an autonomous and elusive laboratory of ideas and strategies. In other words, by way of sidestepping commercial and institutional frameworks, he shifted the contemporary art system’s conventional conditions of production and distribution. He also released Occidental through the film circuit, outside of his familiar terrain of contemporary art, and all the while the exhibitions on view served the artists rather than the system. When he realised after two years that 80% of the funds spent on the enterprise went to renting the space and not into supporting the artists showing there, he decided, in line with the namesake of the initiative, to conclude things. Even though economics is not his strong suit, under the auspices of Occidental Temporary Beloufa enacted his experimental vision of economic equity and support within the art world outside the confines of his oeuvre.

4.

“Any proxy creates a mess – that is the rule. It destabilizes existing orders and dichotomies, undermines fixed structures, just to open a door for humans, packages, or messages to pass. The proxy creates its own temporary world of intervention.”7 – Boaz Levin and Vera Tollman, Proxy Politics: Power and Subversion in a Networked Age

Neïl Beloufa has a lot to say about ‘the enemy.’ “It is efficient, is industrial, is communicative, is designed. It’s something that you don’t think about when you use it—that’s my enemy.”8 The realm that best captures these prevailing forces of communication by design is the Internet. It is noteworthy that this is the very same field of totalising democracy which resonates with Beloufa’s working method of a non-hierarchical arrangement of interests, positions and objects. This also explains his incessant exploration of the impact of the Internet—in particular regarding simulation of transparency and intimacy as well as the accelerated circulation of images and data—on our perception of the world and with one another. For his second solo exhibition at Palais de Tokyo this year, entitled The Enemy of My Enemy, he took up the colossal task of setting his works alongside a selection of other artists’ work of a similar affinity within a curated encyclopaedia of historical events with contradicting themes of politics, artworks, documents and artefacts. Aggressive and inimical in its gesture, the exhibition consists of a complex scenography of collages and miniature dioramas on mobile pedestals, clusters of newspaper headlines, props, museum collections and news footage under keywords such as necrorealism, communication, public space, empathy, and destruction. They were shown in conjunction with tragedies of wars, oppression, dictatorships and injustices in our recent history with the aim of exposing the grim realities of our world. The amplified overload of recycled and appropriated information, all part of the mechanisms of communication and propaganda, seem to put its veracity, and manipulative power to the test. Simultaneously, Beloufa’s system of ‘roaming cenotaphs’ were programmed to move in multifarious ways according to an algorithm. This was to initiate unexpected combinations and unhinge conventional association of ideologies and perspectives within this life-size board game, consequently evoking an image of a self-generative factory of human misery. The overwhelming discomfort imbued in the polarised standpoints can be seen as particularly pertinent in the pessimism and helplessness of the current political climate. The display urgently reminds us of the present state of the world and how we got here, in case we dare forget.

With an excess of reality around us, where does art stand within this overview that Beloufa produces heavy-handedly in the form of a proxy in his exhibition? What is the role of the artist in times of political turmoil? Rarely has he dealt with these questions head on, and for this exhibition he sets art alongside reality as the means to reveal the radical differences in our authority figures’ ability to instrumentalise art and everyday imagery to suit its propagandist agenda. Within Beloufa’s framework, art becomes a field of speculation and of commentary and political action. A teaser of the near future, the exhibition opens with a selection of Beloufa’s works conjuring a paradoxical world of idyllic surveillance (People’s passion…) and boardroom meetings of warmongering nations (World Domination), accompanied by anomalous proto-industrial phyto-pods, thrusting the audience into bleak visions of a world where everything we can imagine goes wrong. Parallel to the world of current affairs, he dives into art history to cite historical positions and works of artists such as realist painter Gustave Courbet – enfant terrible and part of the Paris Commune known for his idiosyncratic anarchism –; Pablo Picasso’s portrait of Stalin; and Joseph Beuys’ video performance of anti-Reagan song Sonne statt Reagan and to his contemporaries such as Hito Steyerl, Thomas Hirschhorn and Pope.L. Antipodal to Beloufa’s fuse of fiction and reality, these artists respond to, and appropriate reality into, autonomous works that repudiate instrumentalisation which become tools of the artist’s own propaganda. When shown alongside the chaotic simulacra of images and symbols of power, these antagonistic pockets are individual reminders of the capability of art and images as resistance. Unequivocally, the exhibition is redolent of Beloufa’s method of editing and amalgamating fragments into a representation of the world, and, via his aggrandising process, these images of power are exhausted and rendered into pure form, stripped of context and content. Recalling what Beloufa told me how he thought exhibitions are like crime scene investigations, apart from functioning as a proxy of our state of affairs, The Enemy of My Enemy could also be regarded as an exhibition of ruins of a dismal world falling apart at its seams. Under Beloufa’s orchestration, our wretched reality is unglued for an instant, and almost like the characters of all his films, all we can do is be confronted by this universe as it is being undone, hoping against hope to find a way out.

Philip K. Dick, ‘How to Build a Universe that Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later’, 1978, https://urbigenous.net/library/how_to_build.html

The author in conversation with Neil Beloufa, in preparation for the text commission, March 2018, the artist’s Paris studio.

Myriam Ben Salah, ‘Neil Beloufa: Essay’, Kaleidoscope Magazine, Issue 26, Winter 2016, p. 105-115.

‘The face cannot be captured by images’ in, Hans Belting and Alexander Kluge in Conversation, Alexander Kluge: Pluriverse, 2018, p. 80.

Hito Steyerl,‘Is a Museum a Factory?’ in, The Wretched of the Screen, 2012, p. 69.

Tron (1982), directed by Steven Lisberger (1982).

‘Introduction’ in, Boaz Levin and Vera Tollman, Proxy Politics: Power and Subversion in a Networked Age, eds. Research Center for Proxy Politics, 2018, p. 11.

Dylan Kerr, ‘I Don’t Think We Should Be Too Serious About Art: Neïl Beloufa on Making Images for a Post-Artist World’, https://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/qa/neil-beloufa-interview-53164