Visqueen is the market leader in the manufacture and supply of structural waterproofing and gas protection systems.1

I met him online. I didn’t know who he was or that we’d ever meet in the flesh. Months later in Paris, between the splayed legs of a sculpture entitled Introducing my Family (2019) at Bétonsalon, I’d recognize his face. It helped that, in our online-video encounter, something seemed to challenge his ability to speak. There he was now, sweater pulled over his mouth, sneakered feet on the window, right rubber-gloved hand holding a stiff, bent, white tube over his crotch.2 Metal, enamel, and rubber; white.

...his desiring body rejects the mother tongue as it would a transplant...

Liv Schulman had put me up to it. She had shared a YouTube link to her episodic video, L’Obstruction (2017), for which she had cast Jean-Charles de Quillacq in a role embodying his artistic bent for delegated performance, sculptural copies, and himself indiscriminately on display. In an interview, he remarked, “My body…is always present [in] my work, not necessarily in its physical form, but in energy—either sexual or affective. It is not only about my body, but also about the bodies of the visitors and what I show them.”3 Recently, the performance Présentation du travail (2020) found him suspended between two chairs for over an hour, at visitors’ hip level. The full body-cast under his clothes, both shell and prosthesis, protection and extension, enabling a spectrum of relations. In Schulman’s video, he stood on the narrow plinth, between the legs of a Michelangelo’s David replica, hanging on the hard white marble calf, one hand fondling the hough. In the middle of a roundabout near Marseille’s Prado Beaches, moving his hips and rolling his shoulders salaciously as he looked into the camera, he would bite his lips and rub his eyes as he strained to communicate. Intermittently he’d snap his fingers, as if to keep a silent beat, regroup, or awaken from self-hypnosis. Trying to recite his inherited legend—the master narrative of white masculinity—he fails, losing himself in the footnotes. Between these legs, the copied work of one of his artistic “fathers,” his desiring body rejects the mother tongue as it would a transplant. Framed by the legacies of art and empire, this desiring body enacts what theorist Rey Chow calls “the reality of languaging as a type of prostheticization, whereupon even what feels like an inalienable interiority, such as the way one speaks, is—dare I say it?—impermanent, detachable, and (ex)changeable.”4 Stone, stutter, and sea; white.

Preamble

I recalled seeing a picture of a more modest plinthed statue on the opposite side of the Atlantic, in Louisiana’s Pointe-aux-Chênes marina, on the edge of terra ferma. It had popped up in my feed, with its bleeding heart of stone, dead tree, and loose electrical wire. Fully-cloaked, its lean-faced Christ stretched his arms5 towards the disappearing Isle de Jean Charles.6 Something ineffable convinced me that these statues had a lot in common. I had to get to the bottom of it. One day, as I was leafing through an Air France inflight magazine, I put my finger on it. INFRASTRUCTURE. The secret was in these coloured lines crisscrossing the globe, drawing out partner airlines’ proprietary routes and joint control of commercial air space. These statues were woven into the vast, common geopolitical design that materialized, in 1830, in the conquest of Algeria, ushering in France’s second Imperial era, and in the passage of the Indian Removal Act in the USA.7 Soon, I thought, as the live flight-tracker on my seat-back screen averred my plane-icon’s progress, Christ may well have to start one of his walks on water. Just as the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw residents of Isle de Jean Charles are being forced to resettle inland, thanks to rising sea levels, oil-industry pollution, and salt-water infiltration that, together, relentlessly devour the island.8 Extraction, contamination, dislocation; polychrome.

What prompted my sudden recall of that Louisiana sculpture? Which neural connections were activated? By what, the image or the legend? Water or oil spills? Or was it high altitude and caffeine? Certainly it had something to do with nomenclature, with the proliferation of names—first, given, middle, last, and surname—coalescing into characters named Jean Charles: de Quillacq, the artist; Naquin, after whom Isle de Jean Charles is named; and Doucet, its stand-in in Benh Zeitlin’s 2012 cult film Beast of the Southern Wild. And Mr. Charlie, the world’s first mobile and submersible drilling rig, built nearby in 1953, whose name is also a euphemism for the white man in African American speech.9 A smart investment, Charlie-the-rig spawned the entire offshore oil-drilling industry.10 Fifty years later, with Isle de Jean Charles irrevocably sliding into the Gulf of Mexico’s corrosive salted waters, Mr. Charlie became a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark. More than names, it also had to do with the island’s elaboration, its replication elsewhere, its reterritorialization inland and in time,11 processes also in play in Jean-Charles de Quillacq’s work. This Louisiana experiment is a blueprint for many internal resettlements to come. “Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed.” A devastating twist on the dynamic equilibrium of Lavoisier’s Law of Conservation of Mass, I thought, as homeostasis subjects community resilience to “coercive mimeticism.”12 The stakes are high. Reterritorialization will seek to yield perfected crops of quantified bodies, docile, grateful, identical, and optimized. Lavoisier met the guillotine and lost his head. Residents had to move and received performance sneakers. Oil, dirt, salt, and tears; black and white.

In addition to its temperature control properties Lumisol Clear manipulates the type and level of light entering the greenhouse to significantly improve crop hardiness, colour, taste and shelf-life.13

Recapitulation

Back at Bétonsalon, the window-born sneakers open onto a spare but vibrant space. And Introducing my Family isn’t the only work headed for the window. Philippa (2017-2019), a long, dark, and open tubular form offers herself to the outside in desiring abandon. Her high-shine length, bending lightly, lingers halfway into the room. Rumor has it that Philippa recently had a name change. She emancipated herself from patronyms. It’s how she managed her newfound fear of heights. She had seen what gravity does to a sculpture that falls. She was there when Horizontal Thoughts (2015), fulfilling its titular promise, hit the ground: broken in two. Philippa wanted to stay whole. She had defied gravity in her prior life. The straps had helped. And she knew her ex-title, Alexandra Bircken (2018), was a disclosure of Jean-Charles’s infatuation with the German artist’s work. Now, their relationship had shifted, from debt to elaboration, from the measured assertions of a full name and artistic lineage to the capaciousness of a first name and an open courtyard. Grounded and freed, Philippa had elected to rest on the window, all-desiring. She no longer sought interaction, no longer needed straps or stamps. She wanted something more, the pleasures of “intra-action.’’14

I sensed that I was intruding. The space between the pitch Philippa and the white sculpture Shopping (2019) was thick with sexual energy. Shopping, a similarly long, shiny, and open-ended tube, ran the length of a white assembly-required IKEA table and reached precariously into the room, in mid-air and away from Philippa, gently bending under its own weight. Exuding a generalized, unbounded desire, Philippa and Shopping could not bring themselves to stand erect as sculpture, much like the character in L’Obstruction failed to come into language. Nor could their older, needy stepsister Charles, Charles, Charles (2016),15 which required the daily care of the art center’s staff who, latex gloved, would rub ointments made of tar, oils, and fat over the sculpture’s three members. It dawned on me that these sculptures flirt with limits.

Contents

Rules are circumstantial with Jean-Charles, I surmised, like car washes.

I stare outside the window of my tenth-floor New York apartment, trying to be present. Self-quarantined, I haven’t been looking into windows much lately. I’ve had to adjust, like everyone else, to looking out … indiscriminately. But old habits die hard and, to escape my computer screen, I find myself peering at the shaded windows of apartments abandoned for safer elsewheres, and across rooftops and pointy water towers. Water, frames, glass… This takes me back to the instances when I found myself peeping into Bétonsalon’s storefront windows at Jean-Charles’s show Ma système reproductive. I grab my mobile to review the images I snapped during my two visits. It informs me that today, being my birthday, US crude oil prices just went negative. Looking at the exhibition pictures, I see objects and images clinging to walls or nestled in corners. Many lay flat or bent, unmade, wrapped, huddled, and spent. Several evoke lazy hardware16 and an augmented body: prosthesis, walker, grab bars, nicotine, Viagra, performance footwear, self-tanner, and Axe body wash. Other works convey something of improvised living with their floor-bound bed, bed sheet, t-shirt, found footwear, and repurposed hoses and pipes—a body on the margins. A few venture forth, alone; most seek protection or invisibility in the group, the denotation of the cluster or the inference of constellation.

Rules are circumstantial with Jean-Charles, I surmised, like car washes. It pleased me because I always brushed rules away. I suspected everyone did. But no one talks about rules this way. Rules are usually parsed or glossed, followed or broken in performances that have distinct architectures, tv channels, toxicities, drug cocktails, and holes. Holes everywhere: in logic, being, space, time, bodies, and socks. Black holes, bullet holes, hellholes, loopholes …and wormholes. In Jean-Charles’s universe, objects were never singular. So there were no objects. They only ever coalesced in multiple, ever-widening relations—with other objects and gestures in a given exhibition, in his studio, within his practice, in the ecology of artists like Schulman, Bircken, and Ray, with whom he entertains mental-material conversations, in events, and in the world. Objects could only conform—literally, “form with”—as part of an ensemble cast in a story enacted with other objects in space, and supported by a title. But only for a moment, and from a limited angle, before they reconfigured themselves.

Cover and Attachment

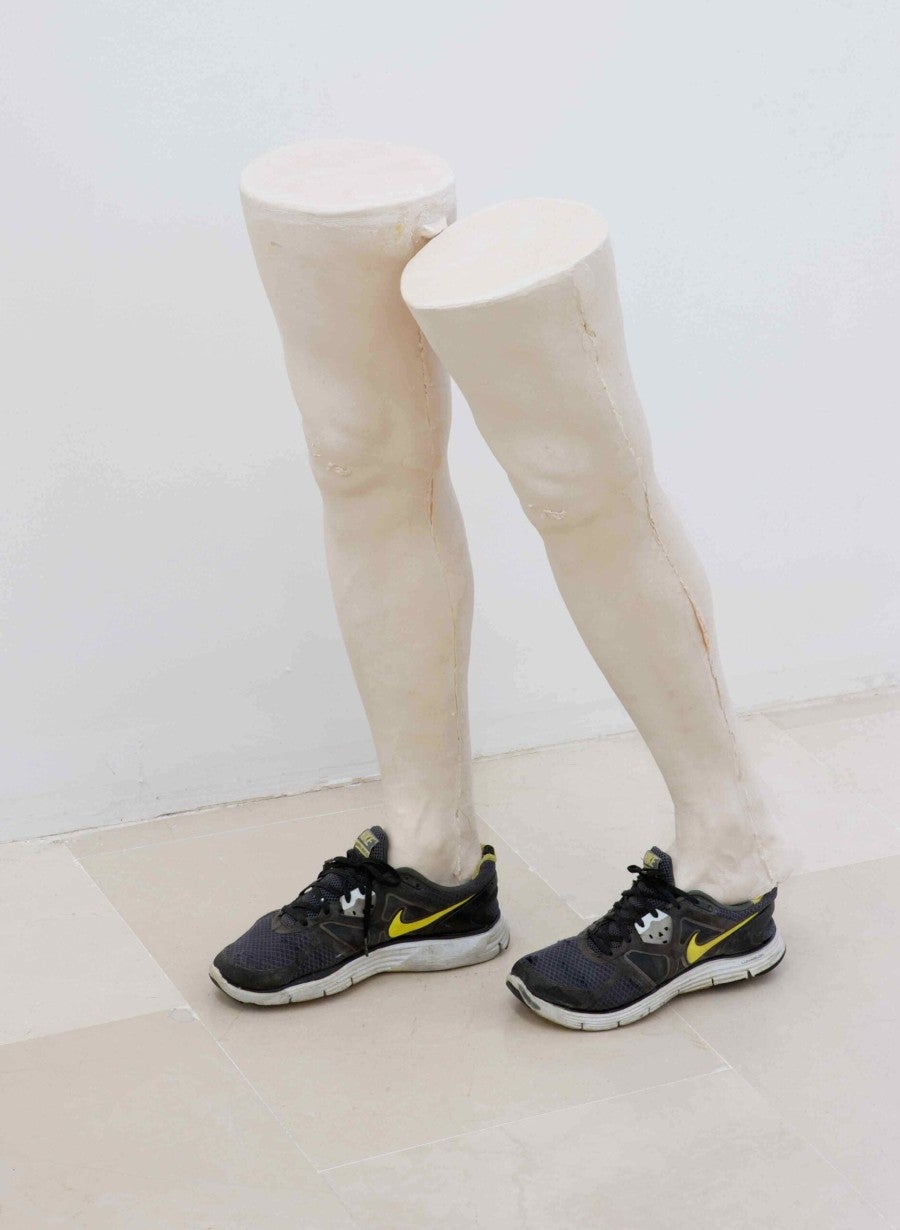

For these objects simultaneously inherit, attract, and deflect affectations. They are desiring, promiscuous, and recombinant. Serially cast in different roles and architectures, they adopt different names and obey diverse impulses, from the curative to the phagic. They proliferate. Group (2019) elaborates on Horizontal Thoughts, a sculpture wherein two white epoxy-resin legs, cast after the artist’s right appendage, awkwardly sport Nike sneakers. In Group, the odd couple gets a third leg, a second-hand prosthesis: a weathered, orange thick-rubber boot—ubiquitous in swampy Louisiana—that washed ashore in the Landes. Rescued by Jean-Charles, the sturdy boot buoyed itself to assist the legs, one of which, broken in two in a previous exhibition, was both visibly re-paired and adorned with a knee brace. Improvised mobility aid, the boot recast the white leg as a disabled limb, much as Alexandra Bircken aka Philippa entered a witness protection program. It’s hard being a sculpture.

Before Group, Blue Jean (2015) had already mobilized three amputated legs. Logical, since the word leg has three letters. I filed the observation under mind-wandering. Focus; cut to the chase. And, leg in reverse is gel. Let it go. Here, left legs conjoin their severance, forming a tripod. Having traded motility for stability, the bound triplets are going nowhere. They exhibit the centripetal force of pure purposeless replication, irradiated. Blue Jean’s sinistral legs display generic variations: these lefties are kissing cousins to the members of Group, Horizontal Thoughts, and My Tongue Does This to Me (2018). Cast in acrylic-resin, an easy-to-use and reliably toxic material, these relatives have achieved a new complexion, courtesy of disposable ballpoint pens. Or was it an all-over tattoo, a pictorial literalization of the “skin tight” qualifier of “jeans”: the iridescent monochrome as ultimate ink? Between performance and sculpture, the process mobilizes severance and transferal. Countless times, the plastic ink tube is extracted from the barrel, its ballpoint tip amputated. One pen after another, the artist blows xenobiotic matter out in a taxing, intimate performance mixing breath, saliva, plastic particles, and ink to cover the entire sculpture. Alchemical, Jean-Charles’s performance turns ink, a medium of inscription, into its opposite—redaction, erasure—reconfiguring both figure and ground.

Footnotes

Legs, feet, socks, and footwear—contact points between the ambulatory body and the world—course through Jean-Charles’s oeuvre. Always cropped, and recruited into provisional assemblages, they speak to both grounding and escape; metaphoric roots and real movement. Surely, the recurring legs are no simple fetishism. That would be so pedestrian. No, the legs are about restlessness and proliferation. I had always been delighted that the word “leg” fulfilled its promise, allowing me to go out on a limb. I often thought that this urge to move had nestled itself into a syllable connecting the law (legal; legit; legitimate), narrative (legend; legible; legibility), inheritance (legacy), and proxy (delegate; legend). I had also heard of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS), “a condition that causes an uncontrollable urge to move your legs.”17 RLS introduced exercise programs on planes. No one flies anymore and Jean-Charles’s work limbers across these different registers. His practice is an anatomy of bodies in parts, prostheticized bodies tenuously sustained by fantasies: physical integrity, gender, the family, history, networks, self-care, and supplements. And since “prosthetics [are] something that can and must be undone and remade,”18 Jean-Charles’s work offers a pulsating world of vibrating matter in constant re-assignment.

Appendix

What precisely is this reflexive tongue: the organ, speech, or a language?

In the 2018 exhibition My Tongue Does This to Me presented at La Galerie – Centre d’art contemporain in Noisy-le-Sec, five legs lean on a white wall, cast replicas of the artist’s right limb, next to pipes, epoxy-covered bent forms, a stiffened leather belt, a curved piece of driftwood, and a mutant leg, unformed below the knee, where its outgrowth sports a white sock. A somewhat clinical display, they conform to the wall-hits-floor 90-degree angle—the crash collision of two planes. Two other limbs in formation hover in the middle of the room. What do these have to do with the tongue and its agency? What does this installation have to do with the fleshy, unruly, and wet extensible organ that allows human and non-human animals to lick, taste, swallow, talk, kiss, and pleasure? What precisely is this reflexive tongue: the organ, speech, or a language? Intimate and indiscriminate. Tongues fork, spit, and slip. Speech runs away from them. Multilinguals court this errancy and translation bears witness to the buoyant kinship between words across languages with tricks of its own: English “false friends” have French “faux cousins.” Capacious and hospitable, tongues host “each one of our ancestors.”19 Tongue is legacy, a delegate, and a dancing partner, giving you a leg up, a way to put your best foot forward or step back. But she’s also fickle, treacherous: chemically advanced, she can be aroused, twisted, caressed, fooled, and stained. The titular tongue has an agency all her own, like all of Jean-Charles’s works. Loose and capricious, she does things. To a footloose, undefined, slippery me. But then again, isn’t a tongue also a flame or a narrow strip of land, like Isle de Jean Charles or Florida seen from outer space? And shoes have tongues too; they come with laces. Tongue, slip, and flesh; untied.

Sneakers act as a chorus in Ma Système reproductive. They appear, obvious, in Group and Le pied humain (2019), and more discreetly in Portrait of my father sleeping (2003-ongoing). Floating up on the wall, Le pied humain is a delegated rendering: a commissioned painting of a sneaker that illustrates a news clipping. The source image shows a sneaker-entombed foot that washed ashore the Salish Sea in Canada. A host of sneakered human remains have been found there since 2007, courtesy of the trenchant buoyancy of performance footwear, shrouding the place in ghostly mystery.20 Some feet have been identified; most have evaded DNA certainties. Theories abound, including that they would be the work of a serial killer, the mob, or the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Bodies can be preserved in salt water for three decades or more and their water-insoluble adipocere—aka corpse, grave or mortuary wax—complicates forensic work.21 Looking at this painted sneaker, I tried to conjure up Jacques Derrida’s ruminations in The Truth in Painting, his “conversation” with German philosopher Martin Heidegger and American art historian Meyer Shapiro around Van Gogh’s shoes, their tongues, and laces.22 Thoughts buoy up… Pairs, eroticism, phantom limbs; elegy.

The clipping itself, covered in a protective “sleeve,” was a component of the ongoing Portrait of my father sleeping, a work whose iterative status and relationship to the studio couch as therapy and matrix. But its diminutive mattress is not for a body, whole; it’s made for its unprostheticized core, like the IKEA table in Shopping. Because machines, like lovers and ghosts, don’t need rest. Beyond Portrait of my father sleeping, two other prostheticized works interpellate the “father”: Mon père en nageur [My father as a Swimmer] (2019), washing me over with flashbacks from the 1968 film The Swimmer, Burt Lancaster, and his swimming trunks, and Father polysexual (2019), obliquely facing the latter and summarily undressed, gray pants bunched on the floor. Both works’ skeletons are made of plastic-covered white metal tubes that riff on grab bars, mobility aids, and table legs. Gold delicately chaining his ankles, the swimmer flutter-kicks his two white-cast paternal legs toward his self-same, poised to enjoy the cigarette attached to each of his knees, under wrap. Autarchic desire, metal skeleton, plastic sheath; white, gold, and gray.

Epigraft

A negative reproduction of Blue Jean graces the cover of BS no 26, the publication accompanying Ma système reproductive. Ghostlike. Also inverted are all the reproductions of works in the show. Near the end of the ”Notices” section, the French illustrated list of works, another “cover” materializes: a copy of the cover of BS no 22, where a white ceramic sock announced Candice Lin’s Bétonsalon exhibition A Hard White Body [Un Corps Blanc Exquis] some 18 months earlier. I am surprised. Why is this sock cover here? Is it a design or printing misstep? But then again, didn’t this slip stop me in my tracks to look at the Notices? Alone, the sock could have passed for Jean-Charles’s work. The questions were short-lived. Another cover—a spare?—reintroduces de Quillacq’s show with the work To Tables (2017) in the next spread: a closeup of the partially formed sock-sporting leg later reassigned to My Tongue Does This to Me. White as a ghost, shaped like a tongue, transitioning on the page and below the knee, it reminded me of Jean-Charles’s small wall-mounted white epoxy sculpture Pistorius-san (2015), his first prosthetic work,23 whose priapic unreliability gives visual form to the toxic failures of heterosexuality and white masculinity. Jean-Charles’s materials are often toxic, like Bisphenol A (BPA)-rich epoxy resin. BPA is a chemical reputed to mimic the structure and function of estrogen.24 Hysterically in some quarters, this came to mean that ingesting the chemical, omnipresent in everyday food packaging, had both “feminized” men and may be leading to their outright extinction.25 Other forms of pollution have been troubling bodies, gender, and their performances. “Changes in the ancient [and current] atmosphere are reflected in the molecules that allow our cells to cooperate to make bodies. The environment of ancient streams shaped the basic anatomy of our limbs….”26 Pollution impacts physiology and consequently self-image and identity,27 said artist Abdullah Al-Mutairi in a recent interview. In our conversations last summer, which I shared with Jean-Charles, Al-Mutairi reflected on the relationship between the Gulf region’s body-building trend, compromised bodies and the toxic legacies of war and petrochemical economies, and new masculinities.

Irradiated legs, socks appended, feet in formation; Jean-Charles’s multiplication of covers discreetly re-assigns the free take-away publication as an artwork, extending the exhibition into the hands, bags, and ultimately the homes, of visitors. And the first work on view, Supplement (2019), could also be taken home. Installed at the reception desk, its altered grab bars covered in epoxy laced with liquid nicotine and self-tanner were meant to be borrowed. This dispersal, a result of replication, echoes the gender-nonconformism of the exhibition’s title. Something is afoot here and reproduction, in various forms and regimes, is for the taking.

Reproductions

A title can attach itself to several works, repeated like a stutter, or like a father calling all his children by the same name.

Jean-Charles’s work often circles around sovereignty, replication, property, kinship, and mimetism. Or, simply, family and familiarity: family as ideology; family as a duplicator or scanner; family as genomic capital; family as investment. Many of his works are titled sister or father, mischievously leading readings onto forms. There have been no mothers since Dead Mother New Problems (2015). Family and gender, his works infer, are very fragile systems. They rely on operations that can be overturned by a slip of the tongue, the shuffle of a few letters. The exhibition title Ma système reproductive summarily feminizes system (a masculine word in French), re-assigning reproduction (and reproductive rights) to the feminine realm. The sleight of hand made me smile, an invitation to homophonic elaboration: Ma “sis” t’aime reproductive (Montrealese translation: my sister likes you because you’re a breeder or my sister likes you to be fertile). Joyously slipping from proprietary system to sovereign kinship, sister love, and the reproduction of worlds-to-come. Echoing Rey Chow’s remarks on coloniality, I wondered what reproduction would “look like if and when it is recast as prosthetic rather than assumed as essentially originary.”28

One might argue that titles are always prostheses. Jean-Charles’s titles are, severally. A work can change title or integrate installations. A title can attach itself to several works, repeated like a stutter, or like a father calling all his children by the same name. Two 2018 performances were titled Le Remplaçant [The Stand-In]. The first was a delegated performance, developed around a hybrid mask, a cast of the face of one of Jean-Charles’s cousins altered to resemble the artist, like an odd reproductive experiment. During the exhibition, Jean-Charles and select individuals—an extended family identified on a list, like an artwork’s materials—took turns wearing the mask as they went around the exhibition and about town.

Later that year, a more intimate six-minute performance for one or two people was also entitled Le Remplaçant. Wearing a silicone mask of himself, with human hair and eyebrows, Jean-Charles engaged in a series of open-ended physical yet protocol-framed encounters with self-elected participants where “in exchange for the complete availability of the artist towards the volunteers, the volunteer will give the artist an imprint of his/her nose.”29 This exchange reconfigures both the artist’s mask and the participant’s nose-cast into relational prostheses. And this relationality is further elaborated as the artist’s mask later reappeared in Introducing my Family, where I first encountered it, and as the cast noses—equal part imprint, trophy, and sculpture—neatly lined up on a blanket in La place des rechanges [The Holding Pen] (2018). Jean-Charles’s performances are often prototypes for sculptures: bodies and objects carry indiscriminate, equal desiring energy.

La place des rechanges translates as the role of spare parts, their rank, and the location where they belong. Spares are replacements, substitutes tucked away from view, remembered in emergencies. Always at the ready, these extras with indeterminately deferred, unspecified yet imminent roles are like the designated survivor in American politics, the flashlight under the sink, zoological safety populations, or an old lover’s number. In La place des rechanges, L-shaped, silicone-covered, epoxy sculptures are nestled next to the nose-casts from Le Remplaçant on a blanket. These forms are both stand-ins and spares: they migrated from earlier work into this temporary constellation… and could move back or forth. The title, and the work, reminded me of Mark Twain’s “spare uncle”:

I had another uncle too. He was a spare uncle. Went to visit a dentist, a certain doctor Tushmaker. To have his tooth out. Well the dentist pulled and the tooth wouldn’t come but my uncle’s right leg come up. Dentist said what are you doing that for? My uncle said because I can’t help it… out came the tooth, its roots were hooked under my uncle’s right big toe and his whole skeleton was extracted with the tooth. They had to send him home in a pillowcase30.

Foreword

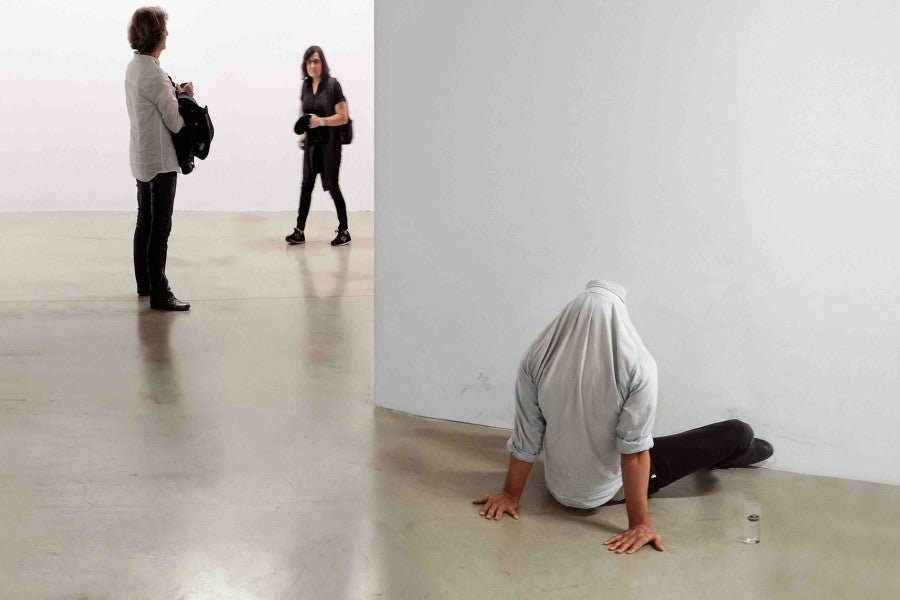

For three days, Jean-Charles cast himself as a stand-in of his work in the group exhibition Vos désirs sont les nôtres. The durational performance, titled Faire Elle [To Be Her] (2018), was also a prototype or prefiguration of sorts for Introducing my Family. Sitting on the gallery’s cement floor, shirt overhead, shoulders rotated, back straight, arms extended and fingers wide, his legs stretched as his feet rested on the gallery wall, like in a pelvic exam. A glass of water nearby. Faire Elle is both a performance, in which the artist literally objectifies himself, and the embodiment of a sculpture-to-come, elaborated as a sequence of works: a pre-stituent more than a constituent, a pre(s)pare i.e. a thing in an indeterminate state preceding spareness. What’s at play here? Is he subjectivizing the object by objectivizing himself? A desire to experience what the sculpture feels? What it feels like to be a sculpture? The enactment of an “alternative method of understanding acquired and embodied practices …that would transcend the classic, rigid division…between subjectivism and objectivism?”31

He imitates Madeleine herself, the subject, rather than her depiction, the object.

“Cry me a River,” sang Ella Fitzgerald in 1955, a year after Mr. Charlie’s success opened the Louisiana coast to oil rigs’ shrilling drilling. Since then, over 484 versions of the song have been recorded,32 and 47 oil rigs are currently in operation in Louisiana, down from 65 in 2019. For his performance L’imitation par les larmes [Recreation by Tears] (2018), Jean-Charles cried his eyes out in front of Philippe de Champaigne’s La Madeleine Pénitente [The Repentant Magdalen] (1657). During the 2018 Biennale d’art contemporain in Rennes, he would often be found in front of the painting in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, weeping fat, round tears like Marie-Madeleine’s, for hours. Artificial and artifactual tears. For centuries, imitation was the cornerstone of artistic training. Many artists surely spent days in front of Madeleine, imitating de Champaigne. And isn’t the pentimento also a well-known artistic strategy? Imitation and repent; Madeleine and pentimenti. Jean-Charles overlays and redirects these two practices. He imitates Marie-Madeleine herself, the subject, rather than her depiction, the object. Can you really see a painting by merely imitating the painter’s stance? What about the agency of the painting itself? The sitter/subject’s smuggled intimations? The painting’s variable currencies as object, image, and contraband? Substantially assisted by menthol, tear gels, and glycerin, Jean-Charles mobilized these questions in his performance. The dual repent, Marie-Madeleine’s and the pentimenti, was a tall order. What happens when you imitate repent, that is, when you re-repent? Looking through veils of tears, you find another face, yours, always different. A while back, I’d read that “we carry the ocean within ourselves, in our blood and in our eyes, so that we essentially see through seawater.”33 Which is to say, that we are, cry, sweat, and spit oceans, literally.

My title is borrowed from an inscription on the plastic covering of Gaëlle Choisne’s greenhouse in her installation Temple of Love – Absence at the Biennale de Lyon 2019. My thanks to Gaëlle for her permission to quote her work. For Visqueen’s brand promise, see https://www.visqueen.com/

A prescient gesture as masks and gloves have been normalized in our post-COVID-19 world.

Isabelle Alfonsi & Jean-Charles de Quillacq, “About The Stand In – Interview,” BS #26 (2019): 19.

Rey Chow, Not Like a Native Speaker: On Languaging as a Postcolonial Experience, New York: Columbia University Press, 2014, 14-15.

An image of this sculpture is included in the article http://projects.aljazeera.com/2015/11/mississippi-dredging/

Elizabeth Rush, Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2018.

The Indian Removal Act swiftly followed the Louisiana Purchase by the USA in 1804, a year which is widely regarded as the end of France’s first Imperial Colonial period. In 1830—nearly 200 years (or 8 generations) ago—Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, also became home to the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw community—a motley crew of African American, Acadian French, and people from three First Nations, who created refuge together at land’s end, in the marchlands-protected bayous, to escape forced resettlements.

The Federal government’s damming of the Mississippi River and the oil-industry exploitation and channelization of the bayou post-WWII collaborated in exquisite public-private fashion to fulfill their geological duty. See, Rush, 23-24.

James Baldwin also titled one of his play Blues for Mister Charlie (1964). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mister_Charlie

See https://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/15813 and http://waterheritage.atchafalaya.org/trail-sites.php?trail=Mr-Charlie-Oil-Rig

In 2016, the Isle de Jean Charles band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians was “awarded” the first climate-related internal resettlement grant by the US government. See http://www.coastalresettlement.org/

Chow, 36.

Karen Barad and Adam Kleinman, “Intra-actions,” Mousse 34 (2012): 76-81.

Presented in the exhibition Tes mains dans mes chaussures at La Galerie - Centre d’art contemporain in Noisy-le-Sec in 2016-2017, Charles, Charles, Charles (2016) is de Quillacq’s homage to Charles Ray’s Oh Charley, Charley, Charley (1992).

Marcel Duchamp’s 1945 window display at Gotham Book Mark in New York was titled Lazy Hardware.

See https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/restless-legs-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20377168

Chow, 15.

Elizabeth Alexander, Praise Song for the Day: A Poem for Barack Obama’s Presidential Inauguration, Saint Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2009, unpaginated.

See https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/real-life/wtf/the-canadian-sea-where-severed-feet-keep-washing-up-ashore/news-story/c61dc3e407dcb3587413c5229d5f346e.

For more sensationalist takes, a partial list of footwear and provenance: https://coolinterestingstuff.com/the-strange-salish-sea-foot-mystery and https://www.foxnews.com/world/mystery-human-feet-washing-ashore-in-pacific-northwest-have-sparked-many-theories-but-whats-the-real-cause

See Jacques Derrida, “Restitutions of the truth in pointing [pointure],” in The Truth in Painting, tr. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1987: 255-382.

The South African Olympic medallist Oscar Pistorius is a double below-knee amputee now best-known for his conviction for the “Valentine’s Day” murder of his model girlfriend.

See, for example, http://www.criticalbench.com/bpas-phthalates-and-the-extinction-of-man/

Neill Shubin, Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5 Billion Year of the Human Body, cited in Stacy Alaimo, “States of Suspension: Trans-corporeality at Sea,” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Summer 2012): 483.

“Byproducts of Development: A conversation between Hamed Bukhamseen & Abdullah Al-Mutairi,” dismagazine.com, 2017, http://dismagazine.com/discussion/84906/byproducts-of-development/

Chow, 34.

Excerpt from invitation emailed to potential participants.

Hal Holbrook, excerpt from Mark Twain Tonight!, a dramatic recitation of selected Mark Twain texts, aired in 1967 as a 90-minute CBS television special. It was nominated for an Emmy Award, and reached an audience of 22 million. https://youtu.be/T8OxDx0ygXA. Thanks to Robert O’Meally for bringing Holbrook to my attention.

Chow, 25.

Julia Whitty, "The Fate of the Ocean," Mother Jones, April/May 2006, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2006/03/fate-ocean/

Chow, 15.