“This is my favorite song to dissociate to”

Author’s note to the reader:

I am delighted to write a text on the practice of the French artist Camille Blatrix. Before this commission, we had not worked together or even met. I had seen his work online, so to gain a substantial understanding of Blatrix’s practice, I needed to experience his work in real life and spend time with his sculptures. Doing so would help me to dip into the spaces around his practice and to look directly at the artwork in a way that could not be done in an exhibition setting or via documentation. So when we did a studio visit in preparation for this text, I asked to borrow an artwork. Blatrix generously agreed to loan me Waiting for Someone (2021), a sculpture from his personal archive.

My original plan was to install the artwork in my studio so I could think about it in my workspace and study the piece during ‘work hours.’ I wanted to write a text with an emotional connection to the artwork. Sharing my office with an artwork means that I need to take it into account in a way that I could not do in an exhibition. I have always found that artworks near to me reveal themselves in ways that I would miss if I didn't visit them or attend to them regularly. I was curious; would a sculpture like Blatrix’ allow me to have such an experience or would it keep me arm's length? Instead, Blatrix suggested that I hang it at home, where I could encounter it in different lights and abundant states of being (tired, rushed, happy, content, angry, and bored), which I indicate in the following text via emoticons: O_o half-awake, |‑O yawning, (@_@) amazed, ^_^ happy and (-_-)zzz sleeping. In the end, my husband and I installed the work in our bedroom as it's the best spot to look at it as I am often here helping my son get to sleep. The natural daylight in this room is also the most beautiful, and as I write this, spring is turning into summer. The room provides a supportive backdrop, connecting well to Blatrix’s use of light, sightlines and so on, as I will go on to discover in the paragraphs below.

o_O

My son taps me on the chest like clockwork. It’s 3am. I know this without checking.

I sit up for an early-morning nursing, but before I am ready, my son promptly curls up on my pillow and goes back to sleep. Without a place to lay my head or even a slither of space to lie down, I sit, looking at the shadowy room around me.

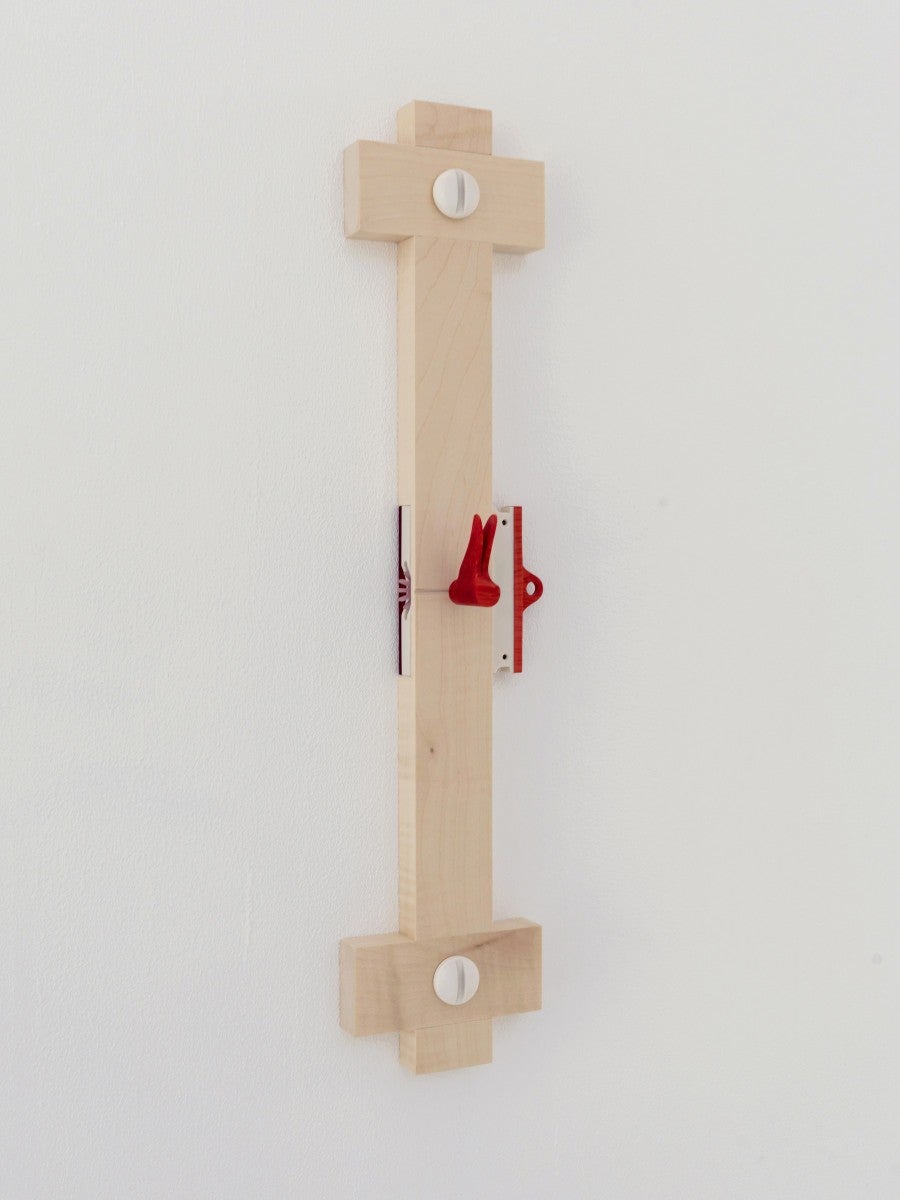

Ahead of me, on the wall to the right of my bedroom door, is Blatrix’s sculpture. In the dimness, the paleness of the artwork merges with the wall.

I perch at the end of my bed, peering closer to see it without my glasses. As I squint, the shape becomes more present, then it is gone again, lost to the shadow.

It may be because I sat up too quickly, but the artwork continuously kaleidoscopes into new shapes—like one of those mash-up videos of different celebrity faces morphing into each other. As in all of Blatrix’s works, the piece is laden with detail, so much so that it is as if I had not looked at it properly before. Instead I was distracted by thinking about what I was looking at.

It is also true this artwork can change because Blatrix has installed the piece in variable ways. The work can be hung vertically to the right or the left and horizontally to the right and left, so there is no "right way up or right way down" and it has the potential to be changed around with every new install. The distance formalist1 sculpture gives a lot of space for different interpretations: Yesterday, my mother-in-law mistook the artwork as a hanging system for a children’s toy, and tomorrow my mother will wonder aloud, as she passes by, why I have a religious clock in the bedroom.

O_o

But right now, as if I have willed it into being, my neighbours’ harsh white light is let in by a wind blowing at the curtains. With artwork in the spotlight, this is my chance to describe it to you:

The body of the wall sculpture is a symmetrical T-bar made of three pieces of maple wood with two large white plastic screw caps on both sides. In the centre, Blatrix has wedged a two-tone (red and cream) shiny plexiglass cog but it is missing its companion piece. The acrylic underside is pulled out of the wood, so there is much to see. The cog cannot function without its companion but cannot be turned anyway, so we do not have to worry about that. Depending on the orientation of the work, the cog’s teeth point away from my direct view. In my bedroom I have to tippy-toe to see the cog's teeth, but if it is installed the other way around, you have to bend down and look up. The plastic could be a missing tool part, which speaks to Blatrix’s workshop. A mechanism like a potentiometer with wings echoes the artist’s interest in music. The winged resin resistor sits in the middle maple bar and feels smooth between the index finger and thumb. It is easy to turn, which my toddler tries to do every time we carry him past the sculpture. In fact, it could be the tiny tapering hands of a clock with a red snakeskin finish, which avid crafters would use to customise their tools.

...the shape becomes more present, then it is gone again, lost to the shadow.

|–O

Later, after writing this description down, I will wonder how to objectively explain these features when I do not have the workshop’s language in my vocabulary. And when I read the description of Blatrix’s artwork to my students, they will tell me that they drifted off to think about other things. Together we will discuss whether my ignorance caused their drift in attention or if the work purposely stirs a ceaseless slippage—in and out of reach. As Gaston Blanchard writes, “[a]t times when we are studying something, we are receptive to a kind of daydreaming.”2

|–O

I ever, ever so quietly get up, and walk past the work, barely breathing so as not to wake my family. Having filled my water glass, I tiptoe back and sit on the edge of my bed. I have the idea something has changed…

Maybe this is a figment of someone’s imagination,

maybe it is my waking dream,

or maybe a scene in a movie.

Now I am invested until the very end.

In the past, Blatrix has referred to his works as artefacts from the near future.3 It’s widely written that he brings these artefacts into being by combining objects he finds in everyday life and giving them a new form. We could call this innovation, except that his selection of daily objects such as coffee cups, bottles, toys, lights, and binoculars no longer function as we might expect them to. Furthermore, Blatrix challenges our material expectations and the authenticity of these objects, by painstakingly crafting them himself. We no longer know them because we never knew them, and to get to know them now, we need to find their future function. Boris Groys writes that art came into being during the French Revolution, when design objects no longer made life better but instead made life worse by taking the form of art. Previously design had served to make tasks and habits easier and forgettable.4

Art problematizes life, and it makes life unforgettable.

(@_@)

Blatrix’s artworks are built of layers that have been finely tuned and sanded down to become one. Paintings become wallpapers, sculptures become walls, supporting and feeding into each other. In his exhibition Pop-Up at Andrew Kreps Gallery in 2021, many artworks were installed at children’s height. For Blatrix, everything is present for a reason, and nothing is left to chance. Even the documentation is worked to deepen the story that the artist envisions. He does so by including elements such as smoke, a body, or another doorway appearing in the photos that were not present in the physical exhibition.

Blatrix approaches making an artwork much like making an exhibition. In the case of Waiting for Someone—the artwork I am looking at right now—all the elements are carefully made by Blatrix in his workshop: cast, cut, planed, sanded, ground, layered, embedded, and finished. He might listen to Slowcore or watch a rom-com, thinking of where this work will be installed in the exhibition. I wonder if the artist’s enjoyment of Slowcore influences his artwork. According to allmusic.com, “In Slowcore, melodies linger forever, and rhythms lurch forward, all shrouded in thick, dank atmospherics.”5 Sound extends time. Sometimes the sound is echoed. Other times the sound is muffled and distorted as if played in another room. The lyrics of the Slowcore genre are mysterious. All of these characteristics can be experienced in Blatrix’s artwork and exhibitions. Blatrix creates tension or brings roughness onto the smoothness of his works by permeating the spaces and encircling the artworks with sound. Sound builds up the space, transforming his exhibitions into movie sets. In New Day Rising, 2018, at the Zurich-based artist-run space Taylor Macklin, Blatrix’s artworks suggest that there has been a heist and the audience might have interrupted the robbery with an unending burglar alarm mixed into the instrumental opening of U2’s 1987 hit single ‘With or Without You’. By choosing music that is immediately recognisable, the artist gives the audience a chance to recall the song, making the soundscape critical to the exhibition and not simply a backing track. Rather than creating ambiance, it creates tension by heightening the audience awareness of where they can and cannot enter. For example, in 2018 at Kunstverein Braunschweig in Germany, Blatrix’s exhibition Somewhere Safer, a soundtrack with the lyric ‘yoooooooouuuuuu’ can be heard through the walls of a room inaccessible to the audience. Adapted from Whitney Houston’s ‘I Will Always Love You’ released in 1992, the word builds and stretches outward, momentarily touching the ears of the listener until it reconnects with the rest of the chorus, ‘I Will Always Love You’. Then it sets off on its own again, leaving the audience wherever they are.

(@_@)

Blatrix’s artworks are not performing. The audience is. And I really have that feeling myself when studying Waiting for Someone. The lozenge-shaped light now casting over my bedroom enhances this sense of waiting. Even though I am in my room, I have tiptoed back into the scene around Blatrix’s artwork that has been unfolding the entire time, waiting for someone to join. “The most concise way to tell them apart is that performance is doing something for the sake of doing it, while performativity brings about change. [...] I am looking, but the ‘work’ makes me do it. Hence, the work is performative.”6 Mieke Bal’s definition of performativity helps me understand why I should be over there… in the direction where the artwork is pointing. For example, the first time that I was looking at Blatrix’s exhibition documentation, I was so busy trying to understand what was happening I didn't even notice the other works in the show until my husband pointed out that Waiting for Someone was also installed there. It is also how I learned the title of the work's name.

...curators have no other choice but to trust that Blatrix will come through with the goods.

|–O

Now, this.

“This is my favorite song to dissociate to” comments listener ‘I want to KMS’ under the YouTube video of Moon Age (1998) by Duster, a Slowcore band Blatrix recommended to me.

|–O

I have come to think of Blatrix as a hard world-builder. He told me that he does not usually share his plans for an exhibition until the day of installation. The curators have no other choice but to trust that Blatrix will come through with the goods. Blatrix is very clear on what the works will be, what they will do, and where they will go, and he is also thinking about how works will move from one exhibition to another. In speculative fiction, “[h]ard world-building means the builder tries to define all the rules of magic, of society and cultures, of the science of their world, of the religions, the species, of the geography (mountains, rivers, lakes, climates, forests, etc.) and so on, to be a consistent setting in which one or more stories take place.”7 The exhibition rules and scenarios are clearly defined, and installations are set right from the first site visit and floor plan. Blatrix’s characters, props, and stage settings unite again and again in new exhibitions. Each threshold and room is a scene, each artwork a character (some have hands and feet, some faces, some nothing at all), leading the audience on the trajectory he wants them to go. The other audience members become background actors (extras) and the pieces that blur between artwork and objects, such as cardboard boxes that return occasionally (for example in Somewhere Safer in 2018 and Les Barrières de l’antique in 2019), might be the props. And by the way, I find the cardboard boxes fascinating, as, for Blatrix, they are not artworks but simply exhibition devices to break up the space. They are pristine boxes, never used for anything other than what they do in the show, adding to the atmosphere but not necessarily meaning anything. When his other artworks need somewhere to hide, Blatrix might install them behind the box, rather than make a new artwork that can function as prop-actor-director.

Blatrix takes into account the sites of his exhibitions using their unique architecture to enhance the larger narrative of his universe made up of corporate logos, letters to the Vatican, early 2000s teen idols, bandaids, Japanese soda bottles, boat hulls, and portals. Somewhere Safer at Kunstverein Braunschweig was sited in Villa Salve Hospes, a converted private residence originally modelled on Renaissance-era Venetian villas. In this exhibition, Blatrix incorporated the shadows of the building’s feature window into the exhibition. Or, in my favourite detail of the exhibition Weather Stork Point, the artist stuck bandaids along the original architectural features of the CAC - la synagogue de Delme—located in an “old, oriental-style synagogue built in the late 19th century.”8 Blatrix also included the feature windows of the repurposed synagogue into his exhibition. Whereas in New Day Rising, Blatrix used the roller doors that feature in the artist-run space to begin the possible narrative of the break-in mentioned earlier. The propped up roller door and accompanying soundtrack also gives the audience a feeling of suspense. “Environments are outside of the skin but brought in through the senses. Their physical shapes experience reality - making us nervous and worried in the case of a catastrophe, bored when nothing changes, and lucky when excitement comes strolling in.”9 All of Blatrix’s staged environments are given exhibition titles that sound like action movies: Heroe, 2016, The Goat + Everyone we know, 2022, Rotten To The Core, 2022, Fortune, 2019, Somewhere Safer, 2018, New Day Rising, 2014, and On Your Knees, 2017. Each artwork is not only a character but an actor and, as I mentioned previously about deflection and performativity, also a director. Here are some actor-directors from the aforementioned exhibition/movies:

Queen bee,

Stork,

The guy at the end of the movie,

Croc,

🤫

Secondary Actor,

Against other and himself,

The GOAT,

Dad,

On the Moon a Wolf,

Winter Guard,

Bingo (Jaune),

Ambird

...Blatrix’s tendency to deflect attention to where he wants us, the audience, to look.

(@_@)

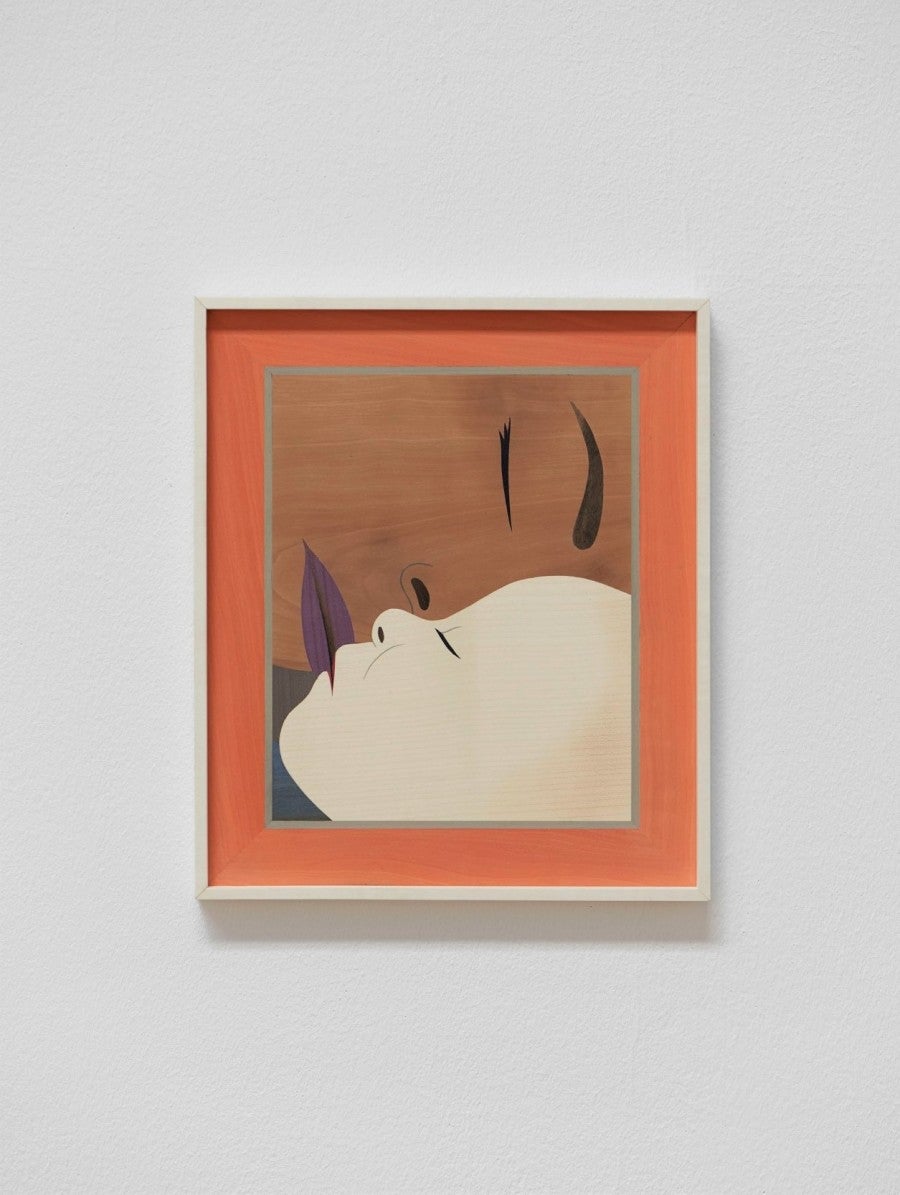

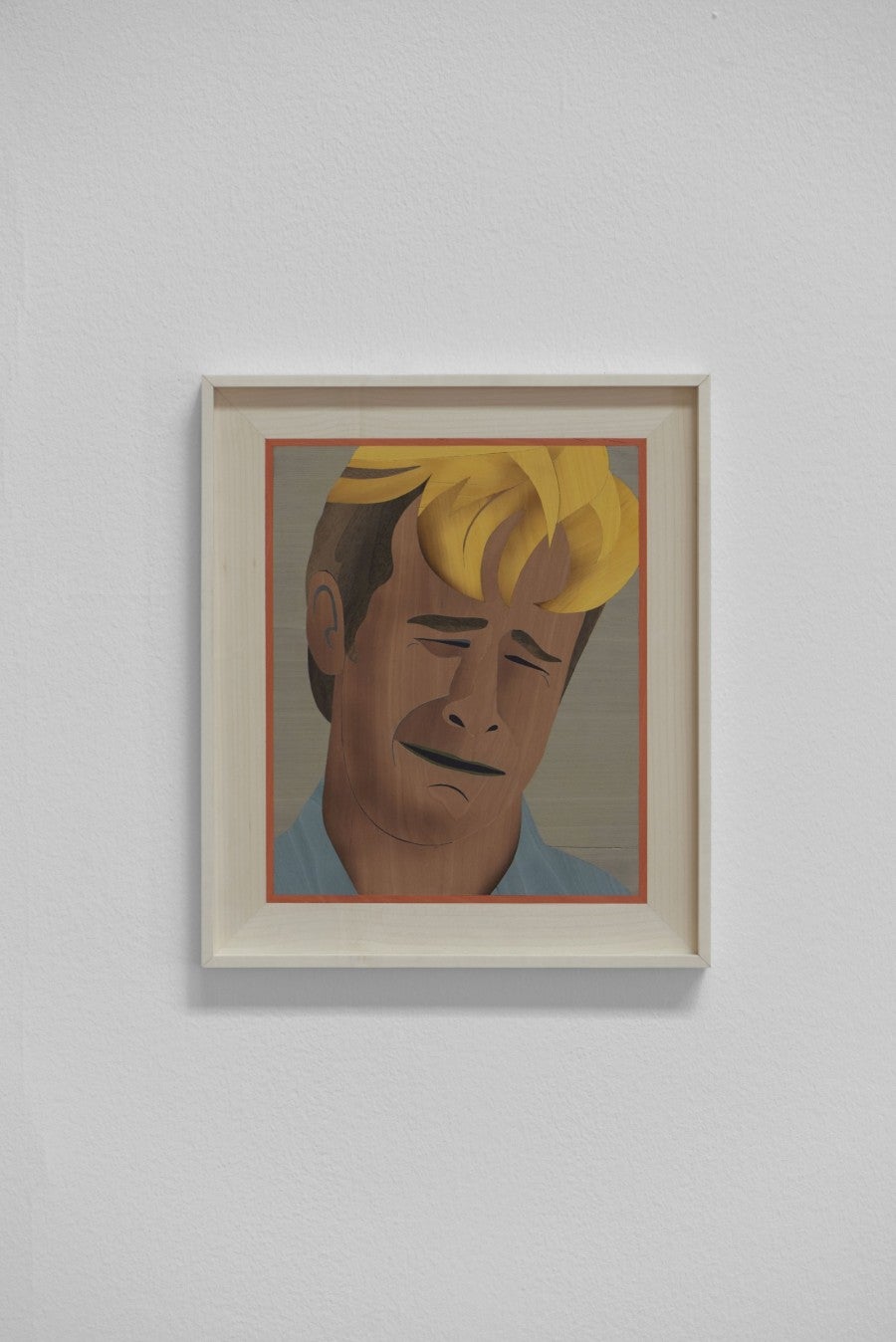

And faces, too, appear in his work. Ugly crying Dawson Leery, the main character from an early 2000s American television show. A portrait of Blatrix as The guy at the end of the movie. A portrait of his wife and daughter. The Starbucks logo. A scribbled face on a scrap of paper. A shushing emoji in silver wrapping around a Japanese soda bottle. A train ticket conductor waiting for the audience to pluck up the courage to buy a ticket. Many lit-up faces can also be found in Blatrix’s marquetry pieces. He heats sand in a frying pan to burn the wood to achieve the gradient effects he is known for. Like a partially illuminated face of someone looking at a smartphone. Light turns up a lot in Blatrix’s work: candlelight is mirrored from the inside of the frame. Daylight from ornate windows casts equally elaborate shadows across the work. Diffused light, sunsets, and lighters. Sculptures can also be lamps and emergency beacons. A hand held up to cover a smiling face blinded with light.

The hand protecting the face is an interesting image to consider in connection to Blatrix’s tendency to deflect attention to where he wants us, the audience, to look. Why should we see everything all the time anyway? Why do we have to know what everything means? On painting (and I think this can certainly be applied to sculpture), the abstract artist Ian McKeever says, “I think that good paintings shouldn’t give you an answer. I think paintings should block you off, they should seduce you, take you into them, but they shouldn’t give you answers, they should push you back out again.”10 By pointing the audience away from his sculptures which seduce, dripping with so much detail, in a way, Blatrix offers the audience some respite. Blatrix even goes so far as to promote the nearest Starbucks on large posters, offering it to the audience as a knowable and familiar place. A place to recover from the art experience, an experience that makes life difficult and (as I mentioned previously) unforgettable.

Other examples of deflection can be found in Somewhere Safer, where Blatrix blocks off a room by installing artwork in a doorway, so the audience can only peer through the threshold. He even nails a beautifully treated plank of wood to the back entrance. And if you dive into the spatiotemporal portals in Weather Stork Point, it will take you back in time to 2020 to visit Standby Mice Station at Kunsthalle Basel, while if you descend through the portal in Standby Mice Station, it will take you to the future to see Weather Stork Point at CAC - la synagogue de Delme in 2022. In the exhibition Unview in 2017 at the gallery Bad Reputation11, Blatrix’s tiny sculptures were installed next to a large window, overlooking a spectacular view of Los Angeles and its sunsets.

^_^

As I sit on the edge of my bed, I wonder why, if Blatrix is a hard-world builder, did he lend me an artwork outside the very precise exhibition conditions that he is known for? Tony Castaldo, a speculative fiction writer and regular contributor to Quora, the social question-and-answer website, commented, “I’m a soft world-builder, but that doesn’t mean anything goes. My stories are always consistent. You won’t find anything on page 50 that contradicts something on page 250; you won’t find anything on page 250 that makes what people did on page 50 dumb or illogical or unnecessary. I just save time in world-building by doing what movie studios do—I only build the sets that will appear on camera, and I make sure those remain consistent throughout the show.”12 Castaldo’s approach as a soft world-builder is akin to Blatrix who demonstrates this most clearly by lending me Waiting for Someone. My experience of his artwork, sometimes amidst the bustle of daily life and now in a waking-half-dream, differs from the experience of his artworks in the exhibition. And still, I do not think that the artist contradicts the narrative he has been building by letting me decide upon the room, the sightlines, the lighting, and the position of the work. That world has slipped into this world, or maybe it’s an opening between the two, an intermundium—stuck inside a spatiotemporal portal. I appreciate Blatrix’s trust. I left his studio with the promise that I would return the work. I carried it home on the train in a tote bag. There is no barrier between me and the work and no deflection unless I choose to turn away from it myself.

|–O

The actor-directors point to other works, people, animals, and characters who point to themselves and back to you. In this case, back at me, and there all along, the artwork’s title gives me direction in the work. The title was not there to tell me something about it. Perhaps it dropped the question mark by accident, maybe while strolling a pram in the park. The artwork title should read: Waiting for Someone? like Wise Character in a movie asking Lost Lover as he stands bemused at the corner, wondering which way to turn. Waiting for Someone asks me, “Who are you waiting for?”

As I stand at the corner wondering which way to turn, the lines from the 1999 synth-pop spoken word piece Everybody’s Free (to wear sunscreen) come to mind:

Don't worry about the future

Or worry, but know that worrying

Is as effective as trying to solve an algebra equation

by chewing bubble gum

The real troubles in your life

Are apt to be things that never crossed your worried mind

The kind that blindsides you at 4pm on some idle Tuesday

Do one thing every day that scares you13

Because that's also what makes life unforgettable, accepting the unknown, which is exactly what art is.

|–O

The ceiling fan drones on, and the clock is still ticking.

|–O

Finally, my neighbour turns out her light.

I gently lift my son back into his cot, and I drift back to sleep.

(-_-)zzz

“Formalism describes the critical position that the most important aspect of a work of art is its form – the way it is made and its purely visual aspects – rather than its narrative content or its relationship to the visible world.” TATE https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/f/formalism retrieved 11 July 2023

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, Penguin Books, New York, 2014, p.21

Camille Blatrix Biography on https://ocula.com/artists/camille-blatrix/ retrieved on 1 July 2023

Boris Groys, ‘Under the Gaze of Theory’ In The Flow, Verson, London, 2016

Pop/Rock » Alternative/Indie Rock » Slowcore, https://www.allmusic.com/style/slowcore-ma0000012160, Retrieved 20 May 2023

Mieke Bal, Endless Andness: The Politics of Abstraction According to Ann Veronica Janssens, Bloomsbury Academic, New York, 2013, p.11

What is hard and soft worldbuilding? Quora discussion board, https://quora.com/What-is-hard-and-soft-worldbuilding, retrieved 20 June 2023

The CAC - la synagogue de Delme, https://cac-synagoguedelme.org/en/7-synagogue-de-delme retrieved 15 June 2023

Jeff Rian,The Buckshot Lexicon, 2000 reprinted in Robert Stadler, Alexis Vaillant (eds.) On Things as Ideas, Sternberg Press, MUDAM Luxembourg, 2017, p 83

Ian McKeever in Ian McKeever Interview: Mystery to the Viewer published on Louisiana Channel YouTube, 20 November 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hh6QbJNvWZE retrieved 28 June 2023

The exhibition was produced in collaboration with Balice Hertling, Paris.

What is hard and soft worldbuilding?, Quora discussion board, https://quora.com/What-is-hard-and-soft-worldbuilding retrieved 20 June 2023

Quindon Tarver, Everybody’s free (To Wear Sunscreen) 1999, as heard on Baz Luhrmann Presents Everybody's Free (To Wear Sunscreen) The Sunscreen Song (Class Of '99) from the label EMI. Lyrics from https://genius.com/Baz-luhrmann-everybodys-free-to-wear-sunscreen-lyrics retrieved 28 June 2023